After starting the day with prayers and songs in honor of the Prophet Mohammed's birthday, the students at the Madrasah al-Irsyad al-Islamiah in Singapore turned to the secular. An all-girls chemistry class grappled with compounds and acids, while other students focused on English, math and other subjects from the national curriculum.

Teachers exhorted their students to ask questions. Some, true to the school's embrace of new technology, gauged their students' comprehension with individual polling devices.

“It's like American Idol,“ said Razak Mohamed Lazim, the head of al-Irsyad, which means “rightly guided.”

A reference to the reality TV program in relation to an Islamic school may come as a surprise. But Singapore's Muslim leaders see al-Irsyad, with its strict balance between religious and secular studies, as the future of Islamic education, not only in Singapore but elsewhere in Southeast Asia.

Two madrasah in Indonesia have adopted al-Irsyad's curriculum and management, attracted to what they say is a progressive model of Islamic education in tune with the modern world. For them, al-Irsyad is the counterpoint to many traditional madrasah that emphasize religious studies at the expense of everything else. Instead of preaching radicalism, the school's in-house textbooks praise globalization and international organizations like the UN.

Leaders in Islamic education here rue the fact that, in much of the West, madrasah everywhere have been broad-brushed as militant hotbeds where students spend days learning the Koran by heart. Still, they were relieved that no terrorism suspect in the region in recent years was a product of Singapore's madrasah, though some suspects were linked to madrasah in Indonesia and other Southeast Asian countries. That association deepened a long-running debate over the nature of Islamic education.

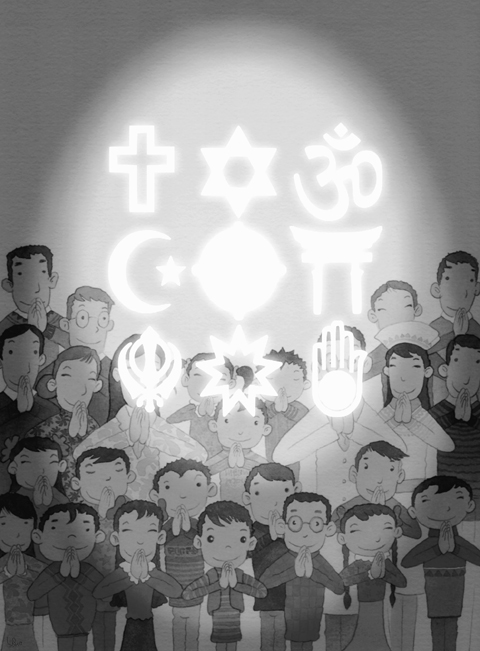

“The Muslim world in general is struggling with its Islamic education,” Razak said, adding that Islamic schools had failed to adapt to the modern world. “In many cases, it's also the challenge the Muslim world is facing. We are not addressing the needs of Islam as a faith that has to be alive, interacting with other communities and other religions.”

In Indonesia, most Islamic schools still pay little attention to secular subjects, believing that religious studies are enough, said Indri Rini Andriani, a former computer programmer who is the principal of al-Irsyad Satya Islamic School, one of the Indonesian schools that model themselves on the school here.

“They feel that conventional education is best for the children, while some of us feel that we have to adjust with advances in technology and what’s going on in the world,” Indri said.

Here, the Islamic Religious Council of Singapore, a statutory board that advises the government on Muslim affairs, gave al-Irsyad a central spot in its new Islamic center. Long the top academic performer among the country’s six madrasah, al-Irsyad was chosen to be in the center as “a showcase,” said Razak, who is also an official at the religious council.

The school's 900 primary and secondary-level students follow the national curriculum of the country's public schools while also taking religious instruction. To accommodate both, the school day is three hours longer than at the mainstream schools.

Mohamed Muneer, 32, a chemistry teacher, said most of his former students had gone on to junior colleges or polytechnic schools, while some top students attended the National University of Singapore.

“Many became administrators, some are teaching and some joined the civil service,” he said.

At the cafeteria, Ishak bin Johari, a 17-year-old who wants to become a newspaper reporter, said the balance between the secular and religious would help the school's graduates “lead normal Singaporean lives compared to other madrasah students.”

That balance resulted, like many things in this country, from pressure by the government. Singapore's madrasah — historically the schools for ethnic Malays who make up about 14 percent of the country’s population — experienced a surge in popularity in the 1990s along with a renewed interest in Islam.

But that surge, coupled with the madrasah's poor record in nonreligious subjects, high dropout rates and graduation of young people with few marketable job skills, worried the government. It responded by making primary education at public schools compulsory in 2003, allowing exceptions like the madrasah, provided they met basic standards by next year. If they fail, they will have to stop educating primary schoolchildren.

Last year, the first time all six madrasah were required to sit for national exams at the primary level, two failed to meet minimal standards, though they still had two more years to pass.

Al-Irsyad, which was the first to alter its curriculum, outperformed the other madrasah. But neither it nor the others made any of the lists of best performing schools or students compiled by the Education Ministry in Singapore.

Mukhlis Abu Bakar, an expert on madrasah at the National Institute of Education who also was a member of al-Irsyad’s management committee in the 1990s, said the madrasah still had a long way to go to catch up with mainstream schools. While Singapore's teachers are among the most highly paid civil servants, the madrasah have had trouble attracting teachers because they rely only on tuition and donations, he said.

“I think al-Irsyad has not achieved a level where I would say it is a model for Islamic education, but ... the system it has in place could become one,” he said.

Still, it began to draw students who would not have attended a madrasah otherwise. Noridah Mahad, 44, said she had wanted to send her two older children to madrasah but worried over the quality of education. With al-Irsyad's adoption of the national curriculum, she felt no qualms in sending her third child.

“Here they teach many things other than Islam,” she said.

Al-Irsyad said it was in talks to export its model to madrasah in the Philippines and Thailand. In Indonesia, Dahlan Iskan, the chairman of Jawa Pos Group, one of the country's biggest media companies, opened a school modeled on Singapore's. And a conglomerate, the Lyman Group, backed al-Irsyad Satya.

Poedji Koentarso, a retired diplomat, led the search for Lyman, visiting madrasah all over Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore.

“We shopped around,” he said. “It was a difficult search in the sense that often the schools were very religious, too religious.”

After more than a year of review, the National Security Bureau on Monday said it has completed a sweeping declassification of political archives from the Martial Law period, transferring the full collection to the National Archives Administration under the National Development Council. The move marks another significant step in Taiwan’s long journey toward transitional justice. The newly opened files span the architecture of authoritarian control: internal security and loyalty investigations, intelligence and counterintelligence operations, exit and entry controls, overseas surveillance of Taiwan independence activists, and case materials related to sedition and rebellion charges. For academics of Taiwan’s White Terror era —

On Feb. 7, the New York Times ran a column by Nicholas Kristof (“What if the valedictorians were America’s cool kids?”) that blindly and lavishly praised education in Taiwan and in Asia more broadly. We are used to this kind of Orientalist admiration for what is, at the end of the day, paradoxically very Anglo-centered. They could have praised Europeans for valuing education, too, but one rarely sees an American praising Europe, right? It immediately made me think of something I have observed. If Taiwanese education looks so wonderful through the eyes of the archetypal expat, gazing from an ivory tower, how

China has apparently emerged as one of the clearest and most predictable beneficiaries of US President Donald Trump’s “America First” and “Make America Great Again” approach. Many countries are scrambling to defend their interests and reputation regarding an increasingly unpredictable and self-seeking US. There is a growing consensus among foreign policy pundits that the world has already entered the beginning of the end of Pax Americana, the US-led international order. Consequently, a number of countries are reversing their foreign policy preferences. The result has been an accelerating turn toward China as an alternative economic partner, with Beijing hosting Western leaders, albeit

During the long Lunar New Year’s holiday, Taiwan has shown several positive developments in different aspects of society, hinting at a hopeful outlook for the Year of the Horse, but there are also significant challenges that the country must cautiously navigate with strength, wisdom and resilience. Before the holiday break, Taiwan’s stock market closed at a record 10,080.3 points and the TAIEX wrapped up at a record-high 33,605.71 points, while Taipei and Washington formally signed the Taiwan-US Agreement on Reciprocal Trade that caps US tariffs on Taiwanese goods at 15 percent and secures Taiwan preferential tariff treatment. President William Lai (賴清德) in