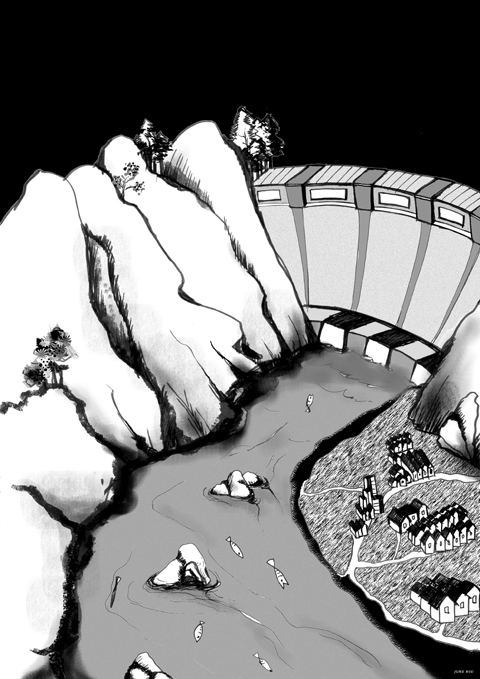

First, the farmers objected to an ambitious dam project proposed by the government, saying they did not need irrigation water from the reservoir. Then the commercial fishermen complained that fish would disappear if the Kawabe River’s twisting torrents were blocked. Environmentalists worried about losing the river’s scenic gorges. Soon, half of this city’s 34,000 residents had signed a petition opposing the US$3.6 billion project.

Last September, this rare grassroots uprising scored an even rarer victory when the governor of Kumamoto Prefecture, a mountainous area of southern Japan, formally asked Tokyo to suspend construction. The ministry agreed, temporarily halting an undertaking that had already relocated a half-dozen small villages, though work on the dam itself had not started.

The suspension grabbed national headlines as one of the first times that a local governor had succeeded in blocking a megaproject being built by the central government. It also turned the governor, Ikuo Kabashima, into a new emblem of a broader rethinking of Japan’s highly centralized style of government, in which Tokyo’s powerful ministries have held a tight grip on decision-making, all the way down to local levels

“We can’t cower before the central government,” said Kabashima, a former politics professor.

The apparent victory brought a flurry of similar revolts by other regional governments against big public works projects. In November, four prefectural governments in the western Kansai region requested the cancellation of a planned dam, and earlier this month the governor of Niigata Prefecture refused to help pay for a new bullet train line. The governor of Osaka said the city would not finance a new bridge to an airport.

This backlash is partly a result of tighter budgets during the current economic crisis. But it also reflects how Japan’s long stagnation has brought growing criticism of the old top-down model, and efforts by regional leaders to change it.

Sensing the shift in political winds, even Japan’s long-governing Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), which ran the old regime along with powerful bureaucrats, has jumped on the decentralization bandwagon. The administration of Japanese Prime Minister Taro Aso says it wants to draw up a bill as early as this year that would replace Japan’s 47 relatively weak prefectures with nine to 13 larger entities that would have powers roughly analogous to US state governments.

It is unclear how realistic the proposal is, given Aso’s own unpopularity and intense opposition within the party and the bureaucracy. But the fact the idea emerged at all underscores how the Kawabe River Dam’s suspension has helped rekindle the debate here over whether to hand more power to localities.

“The Kawabe River Dam is a symbol that Tokyo cannot just impose its will on the regions anymore,” said Yoshihiro Katayama, a political professor at Keio University and former governor of Tottori Prefecture. “Public opinion is shifting against the central government and its missteps.”

In planning the Kawabe River Dam, the government tried to brush aside local doubts about dams going back to an accident 44 years ago when the sudden release of water from a smaller dam during heavy rainfall caused a flash flood that killed one person in Hitoyoshi, in Kumamoto Prefecture.

The suspension also drew national attention because citizen groups played a large role, something unusual in a country used to following Tokyo’s lead. Local environmentalist groups, backed by farmers, fishermen and operators of rafting trips on the river’s rapids, demanded greater openness in decisions traditionally made behind closed doors between politicians and central government bureaucrats. They challenged the Construction Ministry’s arguments that the dam, which was first proposed in the 1960s, was needed for irrigation and flood control.

Under pressure from these groups and prefectural officials, the Construction Ministry made a rare concession, agreeing to hold public hearings to explain the dam and hear residents’ concerns. Some of the hearings devolved into shouting matches between dam opponents and construction industry workers who wanted the jobs, residents said.

In the end, the ministry appeared unable to present a convincing rationale for the project, and opinion polls show that around 85 percent of voters in the prefecture now oppose the dam.

“People realized they could speak up against the national government,” said Nobutaka Tanaka, mayor of Hitoyoshi, who won office two years ago on an anti-dam platform. “In the old days, if officials said it was for the nation, everyone felt they had to be silent and accept it.”

An overreliance on public works spending has also created a huge burden for local governments, which are required to pay a third of the cost of national infrastructure projects. And now, with municipal budgets under increasing strain, local governments are demanding a bigger voice in spending decisions.

Japan’s prefectural and municipal governments are now saddled with some US$2.1 trillion in outstanding debt, substantially below the national government’s US$6.5 trillion but still the equivalent of 39 percent of Japan’s entire economy, the Ministry of Internal Affairs says. By contrast, state and local government debt in the US totals about 16 percent of the US economy, the Census Bureau says.

Early this decade, independent governors in cash-strapped prefectures began opposing public works dictated by Tokyo. The reformist former prime minister Junichiro Koizumi also shifted some tax revenues and fiscal responsibilities to local governments. But never has a local government tried to nix a project as large as the Kawabe River Dam. The backlash has put the powerful Construction Ministry on the defensive. The ministry agreed to a sweeping review of all its dam projects, saying it would make a final decision on the Kawabe River Dam by year’s end.

“They paint us as the bad guys who want big projects,” complained Senior Vice Minister of Construction Yasushi Kaneko, a Kumamoto native who said the Kawabe River Dam was needed for flood control.

Kabashima, who won election last year as a conservative backed by the LDP, said he was on the fence about the dam until he saw the depth of public opposition.

He said that his request to suspend the dam is not a rejection of public works, which Kumamoto still depends on for jobs. Nor is it about saving money, since he said the prefecture will have to spend heavily to clean up the unfinished construction.

“Kasumigaseki’s self-confidence is down,” Kabashima said, referring to the district in Tokyo where the national ministries are located. “Now is the time for Japan to decentralize.”

The return of US president-elect Donald Trump to the White House has injected a new wave of anxiety across the Taiwan Strait. For Taiwan, an island whose very survival depends on the delicate and strategic support from the US, Trump’s election victory raises a cascade of questions and fears about what lies ahead. His approach to international relations — grounded in transactional and unpredictable policies — poses unique risks to Taiwan’s stability, economic prosperity and geopolitical standing. Trump’s first term left a complicated legacy in the region. On the one hand, his administration ramped up arms sales to Taiwan and sanctioned

The US election result will significantly impact its foreign policy with global implications. As tensions escalate in the Taiwan Strait and conflicts elsewhere draw attention away from the western Pacific, Taiwan was closely monitoring the election, as many believe that whoever won would confront an increasingly assertive China, especially with speculation over a potential escalation in or around 2027. A second Donald Trump presidency naturally raises questions concerning the future of US policy toward China and Taiwan, with Trump displaying mixed signals as to his position on the cross-strait conflict. US foreign policy would also depend on Trump’s Cabinet and

The Taiwanese have proven to be resilient in the face of disasters and they have resisted continuing attempts to subordinate Taiwan to the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Nonetheless, the Taiwanese can and should do more to become even more resilient and to be better prepared for resistance should the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) try to annex Taiwan. President William Lai (賴清德) argues that the Taiwanese should determine their own fate. This position continues the Democratic Progressive Party’s (DPP) tradition of opposing the CCP’s annexation of Taiwan. Lai challenges the CCP’s narrative by stating that Taiwan is not subordinate to the

Republican candidate and former US president Donald Trump is to be the 47th president of the US after beating his Democratic rival, US Vice President Kamala Harris, in the election on Tuesday. Trump’s thumping victory — winning 295 Electoral College votes against Harris’ 226 as of press time last night, along with the Republicans winning control of the US Senate and possibly the House of Representatives — is a remarkable political comeback from his 2020 defeat to US President Joe Biden, and means Trump has a strong political mandate to implement his agenda. What does Trump’s victory mean for Taiwan, Asia, deterrence