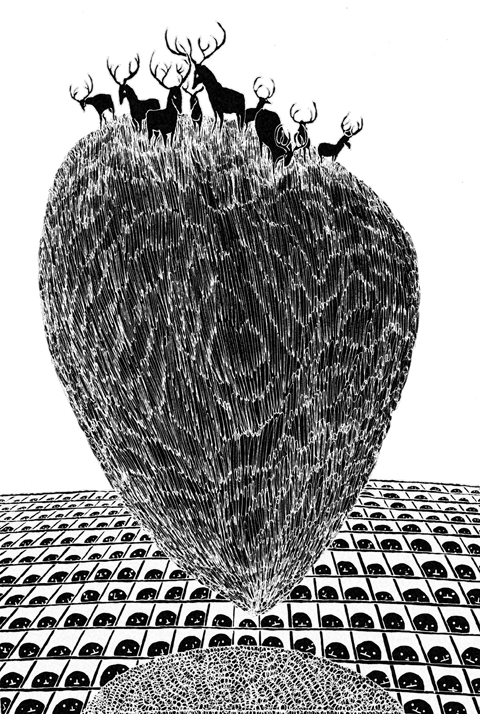

When the mighty elk herds of the West were facing the possibility of extinction from over hunting, settlement and neglect a century ago, people in Jackson, Wyoming, stepped forward and began what has turned out to be a profound biological experiment.

They offered food to the straggling survivors.

The Jackson herd, now tens of thousands of animals strong, became the foundation for a resurgent elk population. After the federal government stepped in to run the feeding system in 1912, a self-reinforcing loop of tourism, hunting, ranching and politics emerged. Having lots of elk in one place where humans would feed them, year in and year out, gradually became a goal in itself, shrouded with complex motives and enshrined by time.

“Habit became tradition; tradition became culture,” said Bruce Smith, who served for 22 years as senior biologist at the National Elk Refuge here, operated by the federal Fish and Wildlife Service.

Now a new and tightening circle of challenges is closing in on the elk and the human system that has sustained them, forcing a debate over the science, emotion and economics of protecting these magnificent animals and the landscape they inhabit. At the center is a critical question: Did human kindness backfire, setting the elk up for disaster?

A federal lawsuit filed last year by a coalition of environmental groups charges that feeding the elk violates the Fish and Wildlife Service’s charter to manage refuges for healthy populations and biological integrity. Feeding programs, the suit argues, endanger the elk and create monocultures that degrade the landscape for other creatures, like birds, which can no longer nest on feeding grounds stripped of willows by the ravenous herd.

Biological threats that could devastate the elk are also looming on the horizon, especially chronic wasting disease (CWD), a neural disorder that spreads by mutated proteins, not unlike mad cow disease. Chronic wasting disease, found in an infected moose last year only about 72km from Jackson, has moved in an inexorable line in recent years from Wyoming’s southeast corner, where it first appeared, to the rest of the state. The disease was discovered in Colorado in the 1960s.

But alternatives to feeding — should a judge order it stopped — have grown more complicated. The valley floors that the elk once used as migration corridors have largely been developed. A boom in oil and gas drilling east of Jackson has created a powerful constituency that wants elk kept on the refuge, out of the way. About 25,000 people tour the refuge each winter and spend money in town when they come.

“It’s like a tar baby — nobody can figure out how to let go of it,” said Bradford Mead, a fourth-generation rancher who is convinced that at some point the feeding must end.

That, all sides agree, would be painful medicine for one stark reason: Fewer elk would, or could, survive, though no one knows for certain what a sustainable number might be. A smaller elk herd would raise the question of whether other parts of the ecosystem have perhaps become dependent. Wolves hunt elk calves and bears, upon emerging from hibernation, sometimes scavenge dead elk.

Then there is the question of what responsibility people have for the system they created.

“We trained them to come,” said Christine Skilton, a sales associate at Images of Nature, a gallery in Jackson that sells nature photography, including pictures of elk.

“We can’t stop now,” she said. “It would be a disaster.”

The Elk Refuge’s manager, Steve Kallin, whose office overlooks the 10,115 hectares where more than 7,000 elk have gathered this winter, said he lived in fear of what could happen if — some people say when — chronic wasting disease breaks out.

“Disease potential has always been recognized — CWD is making it real,” Kallin said on a recent morning.

Kallin said chronic wasting disease, which is 100 percent fatal and has no vaccine, was so unlike other diseases that it was close to science fiction. The prions that carry it to animals are not really even technically alive, he said, and once in the ground, they can persist for years.

But fear of the disease has also paradoxically supported the argument that feeding the elk must not be stopped.

When ranchers first supported feeding in the early 20th century, the goal was to keep the elk away from the hay stored for winter. Now ranchers want the animals kept off private lands because of diseases endemic to the herd, like brucellosis, that could infect cattle. Brucellosis causes pregnant cows to abort their calves.

That creates another feedback loop: Feeding can cause elk to congregate in unnaturally dense numbers, which makes them more prone to brucellosis and other diseases, like foot-rot, not to mention chronic wasting disease, biologists say. This, in turn, fosters greater anxiety in the ranching community about keeping elk segregated.

“If you tried to design a system that would magnify wildlife diseases, you couldn’t do much better than what we’re doing now,” said Thomas Roffe, chief of wildlife health at the Fish and Wildlife Service. “We want to have our cake and eat it, too — lots of elk, but not have them range around on private land.”

Meanwhile, the shift to tourism continues to redefine the local economy. The number of cattle in Teton County has declined by 40 percent since 2001, to about 6,000 animals last year, the Department of Agriculture said. For ranchers like Glenn Taylor, the tough economics of ranching have made side businesses all the more crucial. Taylor runs hunting trips as an outfitting guide, and he said about 80 percent of his guide business depends on elk that the feeding grounds keep in good supply.

“I want to leave things alone,” Taylor said of the debate over feeding, “at least until we find out we should be doing something drastically different.”

Other people say caution must be the watchword.

“We have to be careful that the cure should not be worse than the disease,” said Clarene Law, a businesswoman in Jackson and a former state legislator who opposes an end to feeding.

Like other businesses here, the hotel that Law is a co-owner of is anchored in elk lore: the Antler Inn.

Monday was the 37th anniversary of former president Chiang Ching-kuo’s (蔣經國) death. Chiang — a son of former president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石), who had implemented party-state rule and martial law in Taiwan — has a complicated legacy. Whether one looks at his time in power in a positive or negative light depends very much on who they are, and what their relationship with the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) is. Although toward the end of his life Chiang Ching-kuo lifted martial law and steered Taiwan onto the path of democratization, these changes were forced upon him by internal and external pressures,

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) caucus whip Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) has caused havoc with his attempts to overturn the democratic and constitutional order in the legislature. If we look at this devolution from the context of a transition to democracy from authoritarianism in a culturally Chinese sense — that of zhonghua (中華) — then we are playing witness to a servile spirit from a millennia-old form of totalitarianism that is intent on damaging the nation’s hard-won democracy. This servile spirit is ingrained in Chinese culture. About a century ago, Chinese satirist and author Lu Xun (魯迅) saw through the servile nature of

In their New York Times bestseller How Democracies Die, Harvard political scientists Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt said that democracies today “may die at the hands not of generals but of elected leaders. Many government efforts to subvert democracy are ‘legal,’ in the sense that they are approved by the legislature or accepted by the courts. They may even be portrayed as efforts to improve democracy — making the judiciary more efficient, combating corruption, or cleaning up the electoral process.” Moreover, the two authors observe that those who denounce such legal threats to democracy are often “dismissed as exaggerating or

The National Development Council (NDC) on Wednesday last week launched a six-month “digital nomad visitor visa” program, the Central News Agency (CNA) reported on Monday. The new visa is for foreign nationals from Taiwan’s list of visa-exempt countries who meet financial eligibility criteria and provide proof of work contracts, but it is not clear how it differs from other visitor visas for nationals of those countries, CNA wrote. The NDC last year said that it hoped to attract 100,000 “digital nomads,” according to the report. Interest in working remotely from abroad has significantly increased in recent years following improvements in