I never used to believe in e-books. How could an electronic device hope to replace the beauty of the printed book form, the elegance of its design, the tactile sensation of turning the pages and the smell of good-quality paper? I love libraries. I love bookshops. I love the scent of the leather bindings and the musty pages.

The mere presence of a large number of books induces a profound sense of wellbeing in me.

And this is all still true. But recently I’ve been intrigued by the idea that e-books could be a greener way to distribute the printed word. And since I started using one, my position has begun to evolve.

Printed books are not what they were — many are cheaply produced, smell peculiarly of chemicals and bow or split before you’ve even finished reading them. Many of my parents’ books, paperbacks bought in the 1960s and 1970s, are now unreadable: The glue in the spines has turned to brittle flakes and the pages are yellowed, falling out as soon as you open them. I always thought I’d keep my books forever, but it begins to be clear that they, like so many other products, have a built-in obsolescence.

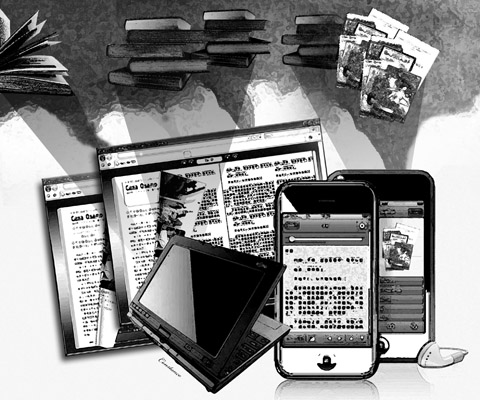

Meanwhile, my iLiad e-book reader is sleek and beautiful. It’s a pleasant object to hold and with its useful page-turning bar, one-handed reading is simple. The matt non-backlit screen is easy on the eye, the design is elegant and unfussy and it is simple to make notes in the text using the stylus or to make the font larger or smaller. Perhaps my attachment to the physical form of the book was a little childish. After all, the words are the same whatever format I read them in and surely it’s the words that matter.

It’s been striking to me how many book-lovers can immediately see the use of an e-book reader. I’ve taken my iLiad to writers’ gatherings, book launches and meetings with editors. The very people I’d have expected to resist it — bookish people, who both read and write a lot — are the people who have looked at it, played with it, cooed over it and said decisively, “I need one of these.” If these people take to the e-book reader with ease, the future of books may indeed be electronic.

And will this be a good thing for the environment? It’s hard to judge. A report by the US book industry study group last year found that producing the average book releases more than 4kg of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere — that’s the equivalent of flying about 30km. Then there’s the cost of warehousing and transport to consider and the waste and toxic chemicals produced by paper mils.

What about the electronic alternative? While the digital books themselves have a relatively low impact — recent figures suggest that transferring one produces around 0.1g of carbon dioxide — there are other factors to take into account. Charging the reader and turning virtual pages all have an energy cost, as does turning on your computer and downloading a file. Even so, the balance may still favor the hi-tech alternative. A 2003 study by the University of Michigan concluded that “electricity generation for an e-reader had less of an environmental impact than paper production for the conventional book system.”

The heaviest burden, though, will be in making the reader itself. If one were to buy an e-book reader, then keep it for 30 years, the impact would be small. But many electronic devices don’t last that long and with the constant advances in processing power and functionality, it’s unlikely that we would want to keep a single e-book reader as long as we might keep a book.

Disposal of electronic items is extremely problematic. More than 6 million electronic items are thrown away in the UK alone every year, and the cadmium from one discarded mobile phone is enough to pollute 600,000 liters of water. Even recycling electronic equipment — or processing them into constituent parts — isn’t without environmental damage.

A recent study by Hong Kong Baptist University examining the environment around a Chinese village intensely involved in e-waste recycling showed that lead levels in the area — including schools — were raised to an extent that might be dangerous.

Paper books are, at least, eventually biodegradable, while e-book readers might pose a lasting environmental problem.

E-books present another ethical problem — piracy. Music piracy has become ubiquitous since the advent of the iPod, and authors might fear e-books for that reason. JK Rowling has refused to allow her books to be produced in digital form and it’s little use buying an e-book reader if you can’t read your favorite authors on it. As an author I’m more cheerful about the possibilities the e-book reader opens up. I may be a foolish optimist, but I doubt the book world will be so rife with piracy as long as publishers act now to allow people to buy e-books cheaply online. The demographics of music fans and readers are different: Seekers of new music tend to be much younger, time-rich and money-poor. Seekers of new literature tend to be older, with less time but more money to spend. The e-book also presents exciting creative possibilities for authors. Imagine being able to create a book that gives different content depending on where the reader is; or one that alters itself as it is read. The e-book could become a whole new art form.

Books have been an object of veneration in our culture for centuries. It is natural — and green — not to want to toss them out. It would be best for the environment if we carried those habits over into the e-book. Just as we strive to prolong the life of printed books, passing them on when we have read them, we need to avoid making the e-book reader another annually replaced gadget. If the e-book revolution is to be a green one, we will need not only robust designs but also a new trade: the e-book repairer.

US President Donald Trump’s second administration has gotten off to a fast start with a blizzard of initiatives focused on domestic commitments made during his campaign. His tariff-based approach to re-ordering global trade in a manner more favorable to the United States appears to be in its infancy, but the significant scale and scope are undeniable. That said, while China looms largest on the list of national security challenges, to date we have heard little from the administration, bar the 10 percent tariffs directed at China, on specific priorities vis-a-vis China. The Congressional hearings for President Trump’s cabinet have, so far,

US political scientist Francis Fukuyama, during an interview with the UK’s Times Radio, reacted to US President Donald Trump’s overturning of decades of US foreign policy by saying that “the chance for serious instability is very great.” That is something of an understatement. Fukuyama said that Trump’s apparent moves to expand US territory and that he “seems to be actively siding with” authoritarian states is concerning, not just for Europe, but also for Taiwan. He said that “if I were China I would see this as a golden opportunity” to annex Taiwan, and that every European country needs to think

For years, the use of insecure smart home appliances and other Internet-connected devices has resulted in personal data leaks. Many smart devices require users’ location, contact details or access to cameras and microphones to set up, which expose people’s personal information, but are unnecessary to use the product. As a result, data breaches and security incidents continue to emerge worldwide through smartphone apps, smart speakers, TVs, air fryers and robot vacuums. Last week, another major data breach was added to the list: Mars Hydro, a Chinese company that makes Internet of Things (IoT) devices such as LED grow lights and the

US President Donald Trump is an extremely stable genius. Within his first month of presidency, he proposed to annex Canada and take military action to control the Panama Canal, renamed the Gulf of Mexico, called Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy a dictator and blamed him for the Russian invasion. He has managed to offend many leaders on the planet Earth at warp speed. Demanding that Europe step up its own defense, the Trump administration has threatened to pull US troops from the continent. Accusing Taiwan of stealing the US’ semiconductor business, it intends to impose heavy tariffs on integrated circuit chips