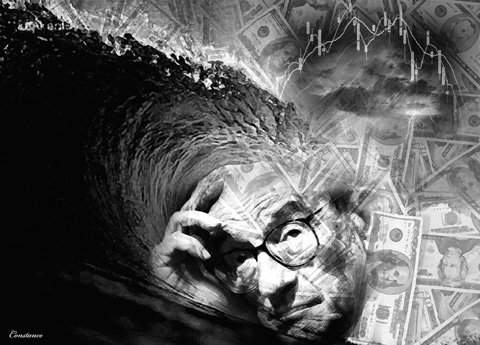

Economics, it seems, has very little to tell us about the current economic crisis. Indeed, no less a figure than former US Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan recently confessed that his entire “intellectual edifice” had been “demolished” by recent events.

Scratch around the rubble, however, and one can come up with useful fragments. One of them is called “asymmetric information.” This means that some people know more about some things than other people. Not a very startling insight, perhaps. But apply it to buyers and sellers. Suppose the seller of a product knows more about its quality than the buyer does, or vice versa. Interesting things happen — so interesting that the inventors of this idea received Nobel Prizes in economics.

In 1970, George Akerlof published a famous paper called “The Market for Lemons.” His main example was a used-car market. The buyer doesn’t know whether what is being offered is a good car or a “lemon.” His best guess is that it is a car of average quality, for which he will pay only the average price. Because the owner won’t be able to get a good price for a good car, he won’t place good cars on the market. So the average quality of used cars offered for sale will go down. The lemons squeeze out the oranges.

Another well-known example concerns insurance. This time it is the buyer who knows more than the seller, since the buyer knows his risk behavior, physical health and so on. The insurer faces “adverse selection” because he cannot distinguish between good and bad risks. He therefore sets an average premium too high for healthy contributors and too low for unhealthy ones. This will drive out the healthy contributors, saddling the insurer with a portfolio of bad risks — the quick road to bankruptcy.

There are various ways to “equalize” the information available — for example, warranties for used cars and medical certificates for insurance. But since these devices cost money, asymmetric information always leads to worse results than would otherwise occur.

All of this is relevant to financial markets because the “efficient market hypothesis” — the dominant paradigm in finance — assumes that everyone has perfect information and therefore that all prices express the real value of goods for sale.

But any finance professional will tell you that some know more than others, and that these people earn more, too. Information is king. But just as in used-car and insurance markets, asymmetric information in finance leads to trouble.

A typical “adverse selection” problem arises when banks can’t tell the difference between a good and bad investment — a situation analogous to the insurance market. The borrower knows the risk is high, but tells the lender it is low. The lender who can’t judge the risk goes for investments that promise higher yields. This particular model predicts that banks will over-invest in high-risk, high-yield projects, that is, asymmetric information lets toxic loans onto the credit market. Other models use principal/agent behavior to explain “momentum” (herd behavior) in financial markets.

Although designed before the current crisis, these models seem to fit current observations rather well: banks lending to entrepreneurs who could never repay, and asset prices changing even if there were no change in conditions.

But a moment’s thought will show why these models cannot explain today’s general crisis. They rely on someone getting the better of someone else: the better informed gain — at least in the short term — at the expense of the worse informed. In fact, they are in the nature of swindles. So these models cannot explain a situation in which everyone, or almost everyone, is losing — or, for that matter, winning — at the same time.

The theorists of asymmetric information occupy a deviant branch of mainstream economics. They agree with the mainstream that there is perfect information available somewhere out there, including perfect knowledge about how the different parts of the economy fit together. They differ only in believing that not everyone possesses it. In Akerlof’s example, the problem with selling a used car at an efficient price is not that no one knows how likely it is to break down, but rather that the seller knows perfectly well how likely it is to break down, and the buyer does not.

And yet the true problem is that in the real world no one is perfectly informed. Those who have better information try to deceive those who have worse, but they are deceiving themselves that they know more than they do. If only one person were perfectly informed, there could never be a crisis — someone would always make the right calls at the right time. But only God is perfectly informed, and He does not play the stock market.

“The outstanding fact,” John Maynard Keynes wrote in his General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, “is the extreme precariousness of the basis of knowledge on which our estimates of prospective yield have to be made.”

There is no perfect knowledge “out there” about the correct value of assets because there is no way we can tell what the future will be like.

Rather than dealing with asymmetric information, we are dealing with different degrees of no information. Herd behavior arises, Keynes thought, not from attempts to deceive but from the fact that in the face of the unknown we seek safety in numbers. Economics, in other words, must start from the premise of imperfect rather than perfect knowledge. It may then get nearer to explaining why we are where we are today.

Robert Skidelsky, a member of the British House of Lords, is professor emeritus of political economy at Warwick University, author of a prize-winning biography of the economist John Maynard Keynes and a board member of the Moscow School of Political Studies.

COPYRIGHT: PROJECT SYNDICATE

There are moments in history when America has turned its back on its principles and withdrawn from past commitments in service of higher goals. For example, US-Soviet Cold War competition compelled America to make a range of deals with unsavory and undemocratic figures across Latin America and Africa in service of geostrategic aims. The United States overlooked mass atrocities against the Bengali population in modern-day Bangladesh in the early 1970s in service of its tilt toward Pakistan, a relationship the Nixon administration deemed critical to its larger aims in developing relations with China. Then, of course, America switched diplomatic recognition

The international women’s soccer match between Taiwan and New Zealand at the Kaohsiung Nanzih Football Stadium, scheduled for Tuesday last week, was canceled at the last minute amid safety concerns over poor field conditions raised by the visiting team. The Football Ferns, as New Zealand’s women’s soccer team are known, had arrived in Taiwan one week earlier to prepare and soon raised their concerns. Efforts were made to improve the field, but the replacement patches of grass could not grow fast enough. The Football Ferns canceled the closed-door training match and then days later, the main event against Team Taiwan. The safety

The National Immigration Agency on Tuesday said it had notified some naturalized citizens from China that they still had to renounce their People’s Republic of China (PRC) citizenship. They must provide proof that they have canceled their household registration in China within three months of the receipt of the notice. If they do not, the agency said it would cancel their household registration in Taiwan. Chinese are required to give up their PRC citizenship and household registration to become Republic of China (ROC) nationals, Mainland Affairs Council Minister Chiu Chui-cheng (邱垂正) said. He was referring to Article 9-1 of the Act

The Chinese government on March 29 sent shock waves through the Tibetan Buddhist community by announcing the untimely death of one of its most revered spiritual figures, Hungkar Dorje Rinpoche. His sudden passing in Vietnam raised widespread suspicion and concern among his followers, who demanded an investigation. International human rights organization Human Rights Watch joined their call and urged a thorough investigation into his death, highlighting the potential involvement of the Chinese government. At just 56 years old, Rinpoche was influential not only as a spiritual leader, but also for his steadfast efforts to preserve and promote Tibetan identity and cultural