The Muslim call to prayer fills the halls of a Cairo computer shopping center, followed immediately by the click of locking doors as the young, bearded tech salesmen close up shop and line up in rows to pray together.

Business grinding to a halt for daily prayers is not unusual in conservative Saudi Arabia, but until recently it was rare in the Egyptian capital, especially in affluent commercial districts like Mohandiseen, where the mall is located.

But nearly the entire three-story mall is made up of computer stores run by Salafis, an ultraconservative Islamic movement that has grown dramatically across the Middle East in recent years.

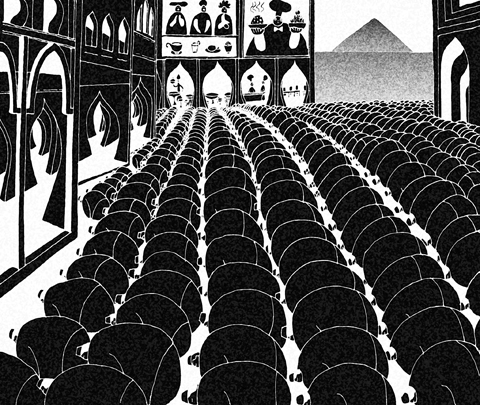

ILLUSTRATION: MOUNTAIN PEOPLE

“We all pray together,” said Yasser Mandi, a salesman at the Nour el-Hoda computer store. “When we know someone who is good and prays, we invite them to open a shop here in this mall.” Even the name of Mandi’s store is religious, meaning “Light of Guidance.”

The rise of Salafists has critics worried that their beliefs will crowd out the more liberal and tolerant version of Islam long practiced in some Middle East countries, particularly Egypt, Jordan and Lebanon. They also warn that its doctrine is only a few shades away from that of violent groups like al-Qaeda, that it effectively preaches “Yes to jihad, just not now.”

In the broad spectrum of Islamic thought, Salafism is on the extreme conservative end. Saudi Arabia’s puritanical Wahhabi interpretation is considered the forerunner of modern Salafism, and Saudi preachers on satellite TV — and more recently the Internet — have been key to the spread of Salafism.

Salafist groups are gaining in numbers and influence across the Middle East. In Jordan, a Salafist was chosen as head of the old-line opposition group, the Muslim Brotherhood. In Kuwait, Salafists were elected to parliament and are leading the resistance to any change that would threaten traditional Islamic values.

The gains for Salafists are part of a trend of turning back to conservatism and religion after major political movements like Arab nationalism and democratic reform failed to fulfill promises to improve the lives of average people. Egypt has been at the forefront of change in both directions, toward liberalization in the 1950s and 1960s and back to conservatism more recently.

The growth of Salafism is visible in many parts of Cairo since its adherents set themselves apart with their dress. Women wear the niqab, a veil that shows only the eyes — if even that — rather than the hijab scarf that merely covers the hair. The men grow their beards long and often shave off mustaches, a style said to imitate the Prophet Mohammed.

The word salafi in Arabic means “ancestor,” hearkening back to a supposedly purer form of Islam said to have been practiced by Mohammed and his companions in the 7th century. Salafism preaches strict segregation of the sexes and resists any innovation in religion or adoption of Western ways seen to be immoral.

“When you are filled with stress and uncertainty, black and white is very good, it’s very easy to manage,” said Selma Cook, an Australian convert to Islam who for more than a decade described herself as a Salafi.

“They want to make sure everything is authentic,” said Cook, who has moved away from Salafist thought but still works for Hoda, a Cairo-based Salafi satellite channel.

In most of the region, Salafism has been a purely social movement calling for an ultraconservative lifestyle. Most Salafis shun politics — in fact, many argue that Islamic parties like the Muslim Brotherhood and the Palestinians’ Hamas are too willing to compromise their religion for political gain.

Its preachers often glorify martyrdom and jihad, but always with the caveat that Muslims should not launch jihad until their leaders call for it. The idea is that the decision to overturn the political order is up to God, not the average citizen.

But critics warn that Salafis could easily slide into more violent, jihadist forms. In North Africa, some already have — the Algerian Salafi Group for Call and Combat has allied itself with al-Qaeda and has been blamed for bombings and other attacks. Small pockets of Salafis in northern Lebanon and Gaza have also taken up weapons and formed jihadi-style groups.

“I am afraid that this Salafism may be transferred to be a Jihadi Salafism, especially with the current hard socioeconomic conditions in Egypt,” says Khalil El-Anani, a visiting scholar at Washington’s Brookings Institution.

The Salafi way contrasts with Islam as it has long been practiced in Egypt, where the population is religious but with a relatively liberal slant. Traditionally, Egyptian men and women mix rather freely and Islamic doctrine has been influenced by local, traditional practices and an easygoing attitude to moral foibles.

But Salafism has proved highly adaptable, appealing to Egypt’s wealthy businessmen, the middle class and even the urban poor — cutting across classes in an otherwise rigidly hierarchical society.

In Cairo’s wealthy enclaves of Maadi and Nasr City, upper-class Salafis dressed in traditional robes can be seen driving BMWs to their engineering firms while their wives stay inside large homes surrounded by servants and children.

Sara Soliman and her businessman husband Ahmed el-Shafei both received the best education Egypt had to offer, first at a German-run school, then at the elite American University in Cairo, but they have now chosen the Salafi path.

“We were losing our identity. Our identity is Islamic,” 27-year-old Soliman said from behind an all-covering black niqab as she sat with her husband in a Maadi restaurant.

“In our [social] class, none of us are brought up to be strongly practicing,” el-Shafei, also 27, added in American-accented English, a legacy of living in the US until he was eight years old.

Now, he and his wife said, they live Islam as “a whole way of life,” rather than just a set of obligations such as daily prayers and fasting during the holy month of Ramadan.

A dozen satellite TV channels — most Saudi-funded — are perhaps the most effective way Salafism has been spread. They feature conservative preachers, call-in advice shows and discussion programs on proper Islamic behavior.

Numerous Salafist mosques in Cairo are packed on Fridays, the day of weekly communal prayers. Outside downtown Cairo’s Shaeriyah mosque, a bookstall featured dozens of cassettes by Mohammed Hasaan, a prolific conservative preacher who sermonizes on the necessity of jihad and the injustices inflicted on Muslims.

Alongside the cassettes were rows of books espousing Salafi themes about sin and Western decadence. One book, The Sinful Behaviors of Women, displayed lipstick, playing cards, perfume and mobile phones on the cover to make its point. Another was titled The Excesses of American Hubris.

Critics of Salafism say it has spread so quickly in part because of encouragement by the Egyptian and Saudi governments, which see it as an apolitical, nonviolent alternative to hardline jihadi groups.

Critics warn that the governments are playing with fire, saying Salafism creates an environment that breeds extremism. Al-Qaeda continues to try to draw Salafists into jihad, and the terror network’s No. 2, the Egyptian Ayman al-Zawahri, praised Salafists in an Internet statement in April, urging them to take up arms.

“The Salafi line is not that jihad is not a good thing, it is just not a good thing right now,” said Richard Gauvain, a lecturer in comparative religion at the American University in Cairo.

The Salafis’ talk of eventual jihad focuses on fighting Americans in Afghanistan and Iraq, not on overthrowing pro-US Arab governments denounced by al-Qaeda. Most Salafi clerics preach loyalty to their countries’ rulers and some sharply denounce al-Qaeda.

Egypt, with Saudi help, sought to rehabilitate jailed Islamic militants, in part by providing them with Salafi books. Critics say the regime of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak sees the Salafists as a counterbalance to the opposition Muslim Brotherhood.

The political quietism of the Salafis and their injunctions to always obey the ruler are too good an opportunity for established Arab rulers to pass up, said novelist Alaa Aswani, one of the most prominent critics of rising conservatism in Egypt.

“That was a kind of Christmas present for the dictators because now they can rule with both the army and the religion,” he said.

The new wave of conservatism is not inevitable, Aswani maintains, noting that his books — including his most popular, The Yacoubian Building — have risque themes and condemnations of conservatives, and yet are bestsellers in Egypt.

“The battle is not over, because Egypt is too big to be fitting in this very, very little, very small vision of a religion,” he said.The Muslim call to prayer fills the halls of a Cairo computer shopping center, followed immediately by the click of locking doors as the young, bearded tech salesmen close up shop and line up in rows to pray together.

Business grinding to a halt for daily prayers is not unusual in conservative Saudi Arabia, but until recently it was rare in the Egyptian capital, especially in affluent commercial districts like Mohandiseen, where the mall is located.

But nearly the entire three-story mall is made up of computer stores run by Salafis, an ultraconservative Islamic movement that has grown dramatically across the Middle East in recent years.

“We all pray together,” said Yasser Mandi, a salesman at the Nour el-Hoda computer store. “When we know someone who is good and prays, we invite them to open a shop here in this mall.” Even the name of Mandi’s store is religious, meaning “Light of Guidance.”

The rise of Salafists has critics worried that their beliefs will crowd out the more liberal and tolerant version of Islam long practiced in some Middle East countries, particularly Egypt, Jordan and Lebanon. They also warn that its doctrine is only a few shades away from that of violent groups like al-Qaeda, that it effectively preaches “Yes to jihad, just not now.”

In the broad spectrum of Islamic thought, Salafism is on the extreme conservative end. Saudi Arabia’s puritanical Wahhabi interpretation is considered the forerunner of modern Salafism, and Saudi preachers on satellite TV — and more recently the Internet — have been key to the spread of Salafism.

Salafist groups are gaining in numbers and influence across the Middle East. In Jordan, a Salafist was chosen as head of the old-line opposition group, the Muslim Brotherhood. In Kuwait, Salafists were elected to parliament and are leading the resistance to any change that would threaten traditional Islamic values.

The gains for Salafists are part of a trend of turning back to conservatism and religion after major political movements like Arab nationalism and democratic reform failed to fulfill promises to improve the lives of average people. Egypt has been at the forefront of change in both directions, toward liberalization in the 1950s and 1960s and back to conservatism more recently.

The growth of Salafism is visible in many parts of Cairo since its adherents set themselves apart with their dress. Women wear the niqab, a veil that shows only the eyes — if even that — rather than the hijab scarf that merely covers the hair. The men grow their beards long and often shave off mustaches, a style said to imitate the Prophet Mohammed.

The word salafi in Arabic means “ancestor,” hearkening back to a supposedly purer form of Islam said to have been practiced by Mohammed and his companions in the 7th century. Salafism preaches strict segregation of the sexes and resists any innovation in religion or adoption of Western ways seen to be immoral.

“When you are filled with stress and uncertainty, black and white is very good, it’s very easy to manage,” said Selma Cook, an Australian convert to Islam who for more than a decade described herself as a Salafi.

“They want to make sure everything is authentic,” said Cook, who has moved away from Salafist thought but still works for Hoda, a Cairo-based Salafi satellite channel.

In most of the region, Salafism has been a purely social movement calling for an ultraconservative lifestyle. Most Salafis shun politics — in fact, many argue that Islamic parties like the Muslim Brotherhood and the Palestinians’ Hamas are too willing to compromise their religion for political gain.

Its preachers often glorify martyrdom and jihad, but always with the caveat that Muslims should not launch jihad until their leaders call for it. The idea is that the decision to overturn the political order is up to God, not the average citizen.

But critics warn that Salafis could easily slide into more violent, jihadist forms. In North Africa, some already have — the Algerian Salafi Group for Call and Combat has allied itself with al-Qaeda and has been blamed for bombings and other attacks. Small pockets of Salafis in northern Lebanon and Gaza have also taken up weapons and formed jihadi-style groups.

“I am afraid that this Salafism may be transferred to be a Jihadi Salafism, especially with the current hard socioeconomic conditions in Egypt,” says Khalil El-Anani, a visiting scholar at Washington’s Brookings Institution.

The Salafi way contrasts with Islam as it has long been practiced in Egypt, where the population is religious but with a relatively liberal slant. Traditionally, Egyptian men and women mix rather freely and Islamic doctrine has been influenced by local, traditional practices and an easygoing attitude to moral foibles.

But Salafism has proved highly adaptable, appealing to Egypt’s wealthy businessmen, the middle class and even the urban poor — cutting across classes in an otherwise rigidly hierarchical society.

In Cairo’s wealthy enclaves of Maadi and Nasr City, upper-class Salafis dressed in traditional robes can be seen driving BMWs to their engineering firms while their wives stay inside large homes surrounded by servants and children.

Sara Soliman and her businessman husband Ahmed el-Shafei both received the best education Egypt had to offer, first at a German-run school, then at the elite American University in Cairo, but they have now chosen the Salafi path.

“We were losing our identity. Our identity is Islamic,” 27-year-old Soliman said from behind an all-covering black niqab as she sat with her husband in a Maadi restaurant.

“In our [social] class, none of us are brought up to be strongly practicing,” el-Shafei, also 27, added in American-accented English, a legacy of living in the US until he was eight years old.

Now, he and his wife said, they live Islam as “a whole way of life,” rather than just a set of obligations such as daily prayers and fasting during the holy month of Ramadan.

A dozen satellite TV channels — most Saudi-funded — are perhaps the most effective way Salafism has been spread. They feature conservative preachers, call-in advice shows and discussion programs on proper Islamic behavior.

Numerous Salafist mosques in Cairo are packed on Fridays, the day of weekly communal prayers. Outside downtown Cairo’s Shaeriyah mosque, a bookstall featured dozens of cassettes by Mohammed Hasaan, a prolific conservative preacher who sermonizes on the necessity of jihad and the injustices inflicted on Muslims.

Alongside the cassettes were rows of books espousing Salafi themes about sin and Western decadence. One book, The Sinful Behaviors of Women, displayed lipstick, playing cards, perfume and mobile phones on the cover to make its point. Another was titled The Excesses of American Hubris.

Critics of Salafism say it has spread so quickly in part because of encouragement by the Egyptian and Saudi governments, which see it as an apolitical, nonviolent alternative to hardline jihadi groups.

Critics warn that the governments are playing with fire, saying Salafism creates an environment that breeds extremism. Al-Qaeda continues to try to draw Salafists into jihad, and the terror network’s No. 2, the Egyptian Ayman al-Zawahri, praised Salafists in an Internet statement in April, urging them to take up arms.

“The Salafi line is not that jihad is not a good thing, it is just not a good thing right now,” said Richard Gauvain, a lecturer in comparative religion at the American University in Cairo.

The Salafis’ talk of eventual jihad focuses on fighting Americans in Afghanistan and Iraq, not on overthrowing pro-US Arab governments denounced by al-Qaeda. Most Salafi clerics preach loyalty to their countries’ rulers and some sharply denounce al-Qaeda.

Egypt, with Saudi help, sought to rehabilitate jailed Islamic militants, in part by providing them with Salafi books. Critics say the regime of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak sees the Salafists as a counterbalance to the opposition Muslim Brotherhood.

The political quietism of the Salafis and their injunctions to always obey the ruler are too good an opportunity for established Arab rulers to pass up, said novelist Alaa Aswani, one of the most prominent critics of rising conservatism in Egypt.

“That was a kind of Christmas present for the dictators because now they can rule with both the army and the religion,” he said.

The new wave of conservatism is not inevitable, Aswani maintains, noting that his books — including his most popular, The Yacoubian Building — have risque themes and condemnations of conservatives, and yet are bestsellers in Egypt.

“The battle is not over, because Egypt is too big to be fitting in this very, very little, very small vision of a religion,” he said.

The US election result will significantly impact its foreign policy with global implications. As tensions escalate in the Taiwan Strait and conflicts elsewhere draw attention away from the western Pacific, Taiwan was closely monitoring the election, as many believe that whoever won would confront an increasingly assertive China, especially with speculation over a potential escalation in or around 2027. A second Donald Trump presidency naturally raises questions concerning the future of US policy toward China and Taiwan, with Trump displaying mixed signals as to his position on the cross-strait conflict. US foreign policy would also depend on Trump’s Cabinet and

The return of US president-elect Donald Trump to the White House has injected a new wave of anxiety across the Taiwan Strait. For Taiwan, an island whose very survival depends on the delicate and strategic support from the US, Trump’s election victory raises a cascade of questions and fears about what lies ahead. His approach to international relations — grounded in transactional and unpredictable policies — poses unique risks to Taiwan’s stability, economic prosperity and geopolitical standing. Trump’s first term left a complicated legacy in the region. On the one hand, his administration ramped up arms sales to Taiwan and sanctioned

The Taiwanese have proven to be resilient in the face of disasters and they have resisted continuing attempts to subordinate Taiwan to the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Nonetheless, the Taiwanese can and should do more to become even more resilient and to be better prepared for resistance should the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) try to annex Taiwan. President William Lai (賴清德) argues that the Taiwanese should determine their own fate. This position continues the Democratic Progressive Party’s (DPP) tradition of opposing the CCP’s annexation of Taiwan. Lai challenges the CCP’s narrative by stating that Taiwan is not subordinate to the

Republican candidate and former US president Donald Trump is to be the 47th president of the US after beating his Democratic rival, US Vice President Kamala Harris, in the election on Tuesday. Trump’s thumping victory — winning 295 Electoral College votes against Harris’ 226 as of press time last night, along with the Republicans winning control of the US Senate and possibly the House of Representatives — is a remarkable political comeback from his 2020 defeat to US President Joe Biden, and means Trump has a strong political mandate to implement his agenda. What does Trump’s victory mean for Taiwan, Asia, deterrence