Once upon a time — not so long ago, actually — the UK university admissions service UCAS was considered by many young British people to hold the golden ticket to adulthood. Having selected your university choices, you’d sit tight and wait for the offers — offers that you knew would change the course of your life and cut those apron strings with a pleasing snip.

How things have changed. Parents have been granted a license to manage their offspring’s university applications for the first time. One in 10 of this year’s half a million university applicants have ticked a new box on the form that enables them to name a parent or guardian as their agent, allowing them to act on their children’s behalf in the fight to get a place at university.

“Your experience of form-filling will be invaluable to your child!” the UCAS Web site boasts.

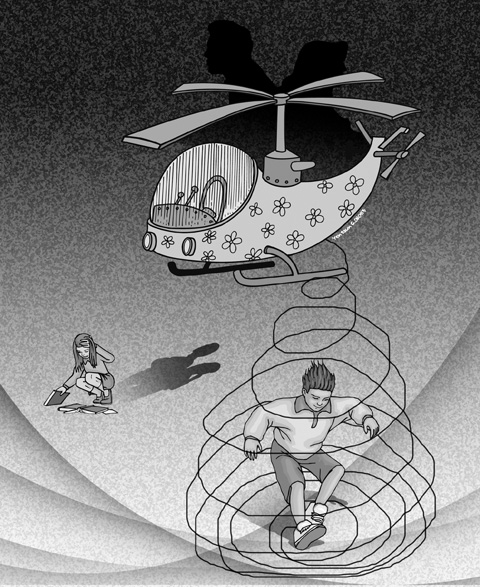

Welcome to the age of helicopter parenting, so named because these moms and dads hover closely overhead, rarely out of reach, whether their children need them or not. Even having arrived at university, students are increasingly found to be phoning mom and dad during lectures and asking them to attend open days and careers fairs. Huddersfield University in northern England has had to set up a “family liaison officer” to feed information to parents round-the-clock about their kids’ progress.

Graduation isn’t even the rite of passage it once was. One major accounting firm reports that it has had mothers pretending to be their graduate children’s secretaries so they can find out more about the job they’re applying for and, at Hewlett-Packard, parents have gone as far as trying to negotiate their son’s or daughter’s salary or relocation package.

No wonder the mobile phone has been termed “the world’s longest umbilical cord.” With parents admitting to calling their offspring several times a day well into their 20s, they are essentially micro-managing their lives. So used to being able to communicate with them 24/7 (not to mention chauffeuring them to every “enrichment activity,” taking on their school projects, badmouthing teachers who tell them off and being their all-round best friend) that they think nothing of making calls both to and on behalf of their adult offspring.

“I want to make sure you don’t offer my daughter an overdraft, as she doesn’t deal well with debt”; “My son won’t be coming into work today, he’s got a cold”; and “My daughter always travels first class. Is she really expected to travel second class on business?” are all genuine examples.

Far from begging mom and dad to please, please give it up, many over-18s seem to welcome such indulgence. In one case, a new recruit to a transport company was overheard on the phone to his mother, saying: “I have got to go to London tomorrow and they haven’t even told me how to get there.”

“The employer threw up her hands in anger and frustration — here was someone working for a transport company, was 21 and had spent three years at university who was aggrieved because he hadn’t been given a detailed map,” said Carl Gilleard, chief executive of the Association of Graduate Recruiters (AGR), who reports that such examples are not rare.

Sue Beck makes no apology for offering to attend job interviews with her 25-year-old daughter and sees no irony in offering the explanation that children are “slower to grow up these days.”

“Sometimes she’ll ask me to do things like call the doctor to say she’ll be late, and until recently, there were a few times when she wanted me to phone her work to say she’d be late or that she was ill. I’m happy to help. Why not?” Beck said.

Bank managers, universities, employers, landlords and the rest of society could, of course, tell these parents and their offspring to get a grip. But what is actually happening, as UCAS illustrates, is quite the opposite.

Newcastle Business School at Northumbria University in northern England is by no means exceptional in its decision to run special sessions for parents.

“In the past, parents wouldn’t typically come to university open days, but in the past three years it’s become the norm,” said Tim Nichol, associate dean for undergraduate programs.

“We felt the only way round it was to start running two sessions — one for the students and one for the parents, who seem to be particularly interested in the UCAS application system, as well as the finances, accommodation and even meeting the academics,” Nichol said.

Intrigued by just how much influence parents have over their offspring’s decision, Nichol decided to carry out a survey.

“We found that 80 percent say their parents have a lot or some influence,” he said.

Just 2 percent said they had none at all — a far cry from my own experience in the 1980s, when my friends and I would rather have given up drinking for a year than ask our parents where we should go to university. Most of us knew the answer already — as far away as possible — whereas a growing number of today’s undergraduates are studying at the university nearest to their family.

At Keele University in central England, a staggering 70 percent of all complaints come from parents. These range from “Why hasn’t my child got a place in medical school?” to “I realize that my daughter failed a couple of exams, but does that really mean she can’t go into her second year?”

But Helena Thorley, an academic registrar, believes there are advantages to this.

“Unlike many students, they understand organizations. So while parents might start off cross or defensive, once we explain why we can’t prioritize their son out of the 500 other people who we’re also finding accommodation for, they do seem to accept it and be able to explain to him,” she said.

It’s no coincidence that helicoptering has coincided with students in the UK — i.e., their parents — having to pay tuition fees, universities believe. And their financial involvement doesn’t stop there, according to Hamptons estate and letting agents, which reports that more and more parents are paying for their undergraduate — and even graduate — offspring’s rent upfront, often a year at a time.

“I’ve just let my own property to a 26-year-old, whose parents have paid a year’s rent in advance,” says Phil Tennant, regional sales director. “For any landlord, that’s obviously nice, so of course we encourage it.”

Actually buying their offspring houses, as former British prime minister Tony Blair and his wife did, is increasingly popular, too.

“Alternatively, they’ll pay a proportion. At the top end, it might be that their daughter is starting at Goldman Sachs on a £50,000 [US$88,000] salary and mum and dad pitch in so that she can afford a one-bedroom flat in a nice part of London, which starts at around £325,000,” Tennant said.

Grandparents are even getting involved in over-18s’ lives at Manchester Metropolitan University in northern England.

“In the past couple of years, we’ve seen a significant increase in the number of grandparents who drive them to half a dozen open days,” says Susan McGrath, head of recruitment and admissions. “Anything that increases the chances of applicants making good decisions is to be welcomed, although I think the parents and grandparents can influence their children too much sometimes. That worries me because an adult who makes their own decision is far more likely to stick with that decision and be successful.”

Parents have been known to call the clearing helplines saying things like: “My daughter’s out of the country/in bed and I need to get her a place.” “Personally, I’d never agree to that without speaking to the applicant,” said McGrath, who added: “I think it becomes particularly dangerous when the parent acts as though they were the child, using language like. ‘We would like ...’”

Other universities, including Liverpool in northwest England, are drawing the line at careers fairs. It’s not that they’re judging parents. They understand all too well that parents have been encouraged to take an active role in their children’s education and long-term future. In fact, many universities say they see increased parental involvement simply as a reflection of how friendly we are with our children now. It’s just that it’s becoming too difficult to identify who the jobseekers are.

Donna Miller, European human resources director for Enterprise Rent-A-Car, did a double-take when she started noticing parents at careers fairs two years ago.

“They come right up to us and say: ‘What would my son be doing if he worked for you?’ while the son is standing right there. It’s like they’re asking about a nursery place,” she said.

The next thing she knew, parents were turning up at their offspring’s job interviews.

“Again, we were amazed, although we try to be polite and say, ‘Gosh, it’s lovely you’re here, but can you wait in reception?’ Most recently, we’ve seen parents responding to the job offer, asking: ‘What will they be doing? Can you explain the benefits? My son doesn’t understand what a stakeholder is,’” she said.

Miller, who works both in the US and the UK, believes that what sociologists have called the “infantilization” of society is more prevalent in Britain.

“It has become so common that we’ve taken the attitude: ‘If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em.’ It’s the way it is for this generation so if you can’t include their parents, you risk missing out on talent,” she said.

To this end, Enterprise increasingly involves parents and even offers to send them a welcome package. Snippets from the personalized letter from the managing director include: “With the recent hire of your son ‘Brett,’ I would like to take this opportunity to tell you about Enterprise ...” and “I am very happy that your son ‘Brett’ has decided to join us. You can be assured that the choice was a good one.”

Other employers take a different view.

“I was shocked when a mother called up and said: ‘I’ve seen a job online. I’d like to inquire about it on behalf of my son,’” says Liz Moss, UK human resources manager at the international public relations firm, Lewis.

“I mean, if someone in their 20s who wants to work in PR — which is a communications industry — hasn’t got the confidence to call us up himself, then I think it’s only fair that we reject him,” Moss said.

The utility company RWE npower is grateful for such attitudes.

“The more firms that attempt to stop moms and dads at the door, the more chance npower has of being an employer of choice among parents,” graduate recruitment manager Bob Athwal said.

“Parents have become best friends, even mentors, to their children and why should we be frightened of that? I don’t see what’s wrong with them coming to careers fairs or induction weeks. In fact, I’d have no problem hosting a dinner just for parents to meet senior management — anything to reassure them. I intend to use this trend to our advantage,” Athwal said.

Sherrilynne Starky, managing director at Strive PR on the Isle of Man, isn’t convinced.

“The father of a 21-year-old new hire called me up the week before her start date to let me know she was particularly sensitive and emotional and would be best suited to work in a harmonious environment. That was three months ago. He was right — this week I gave her a bit of a pep talk asking her to think about the quality of her work. She immediately ‘defriended’ me on Facebook. Today’s her last day,” Starky said.

Not every helicopter parent wears the T-shirt with pride (there really are T-shirts available).

“My 20-year-old son is horrifyingly attached to me. This summer, he called us from a trip to Canada to ask what he should do because the car had broken down. I genuinely want him to make his own way in life, but it seems we’ve given him too comfortable a life and now he doesn’t even want to move out,” Karen Jones said.

Sarah Briggs — a university communications manager who admits that she’s only just weaned herself off helicoptering her two children, aged 20 and 25 — puts it down to her own experiences of growing up in the baby-boom generation.

“Our sheer numbers caused us to compete strenuously for places on sports teams and at the top of the class, for admission to the best colleges and later the best graduate and professional schools, and finally for the top jobs. As our children have come along, we have felt compelled to make the way easier for them, to clear away the obstacles that may lie in their path to success,” Briggs said.

Baby-boomers, Briggs believes, have made nurturing an extreme sport. Like many of her peers, she would regularly put in requests at school for specific teachers to ensure her kids got the best, as well as monitoring their deadlines and lining up their summer jobs.

“While my husband and I have worked hard to ensure that our children are independent thinkers, we still inject ourselves into their decision-making far more than our parents did in ours. ‘Never leave anything to chance’ has become our mantra in parenting,” she said.

Patricia Somers, an associate professor at the University of Texas at Austin — one of very few academics to have studied helicopter parenting — believes this rejection of the less-attentive child-rearing style of baby-boomers’ own parents should not be underestimated.

“Many of them were latchkey children who don’t want to replicate that same level of removal from their own kids’ lives,” she told Kay Randall in a feature that appears on the university Web site.

When their children are called to the headteacher’s office to be disciplined, it’s often they who arrive at the office before the child, she said.

Somers believes technology is equally significant. One minute, you’re setting up a nanny cam, the next you’re regularly texting your 14-year-old — then your 24-year-old daughter.

“It’s just extremely easy to cross the line between being involved in a child’s life to being overinvolved,” she said.

And — although this is more relevant to the US — she says parents’ safety concerns have escalated massively since incidents such as Sept. 11 and Columbine.

“They worry more about children being far away from home and feel helpless to protect them,” she said.

Somers has found that helicoptering is not an exclusively middle or upper-class phenomenon.

“All income levels are represented to some extent, as well as both genders and every race and ethnicity. We did find, however, some differences between how mothers and fathers hover,” she said.

Indeed, she and her colleagues discovered that about 60 percent of helicoptering is by mothers who remain hyper-involved in the social, domestic and academic life of their sons. Meanwhile, fathers tend to intervene in and correct “big picture” issues such as bad grades or refunds, often invoking their real or imagined positions of power, title and support in order to intimidate staff.

Such is the extent of helicoptering that some US universities have started offering counseling to students and introducing policies focused on gradual disengagement. The problem back here is that although there is undoubtedly some resistance to over-parenting, UCAS looks set to pave the way in the opposite direction — entrenching into our society even further the message that Generation Y are incapable of taking care of themselves, a diva generation unwilling or unable to learn from their own mistakes and address their own disappointments in life. And that’s not fair on them.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion