Rajesh was 14 when he disappeared. Beneath a mop of jet black hair, his clear brown eyes glance sideways out of the picture that is all his family have left of him.

He was his parents’ only son and they doted and relied on him. One morning in April last year, his mother, Sunita, asked him to go out to fetch water. She remembers him loading the empty plastic containers on to his cart and setting off cheerfully down the lane. It was the last time she saw him. Rajesh, like tens of thousands of other Indian children every year, had simply vanished.

“It would have been better that he died,” she says, tugging at her headscarf and dabbing at tears. “At least then I would have known, but now I don’t know whether he is alive or dead.”

Official figures show that 44,000 children disappear each year in India. Some are eventually recovered, but one in four remain untraced. Yet, with many parents reporting that police are reluctant to register cases or investigate and other parents complicit in the sale of their own children, the true figure is believed to be much higher — with some estimates of up to a million children every year.

Investigations by Indian authorities and aid agencies have found that many children are kidnapped and sold for adoption, into slavery, or worse. They believe that some end up in the UK.

A new report by India’s human rights commission says that while some of the children are killed almost immediately, others are “working as cheap forced labor in illegal factories/establishments/homes, exploited as sex slaves or forced into the child porn industry, as camel jockeys in the Gulf countries, as child beggars in begging rackets, as victims of illegal adoptions or forced marriages, or perhaps worse than any of these as victims of organ trade and even grotesque cannibalism.”

Every day there are pictures in the classified sections of children who have vanished. “Search for kidnapped boy,” one ad began last week. “Abhayjeet Singh, 13, 5’2’. Kidnapped on 13 August in Prashant Vihar.”

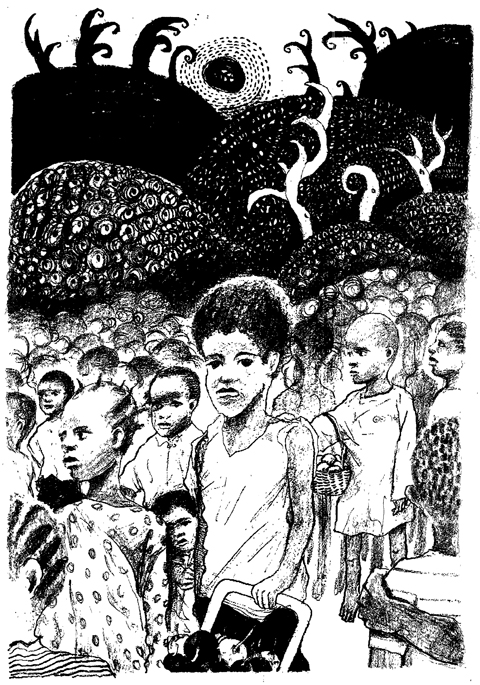

Hundreds more are listed in the books of organizations trying to help the parents who search for years in the hope of finding their lost children: Anikat, eight months old, missing since July 2003; Sultana, 5, disappeared in 2007; Nitesh Kumar, 7; Sunita, 5 ... the list goes on.

The plight of the disappeared has been brought home to India by revelations about the abduction and sale of children, often to order. An adoption agency and orphanage trading in Chennai as Malaysian Social Services is accused of acquiring children from criminal gangs who had taken them from the poorest parts of southern India.

The children were renamed and prospective adoptive parents were presented with faked pictures of mothers they believed were offering the children up for adoption. Seven people have been arrested after some of the children were found in Australia. A previous investigation into another Indian agency revealed that two children adopted by an Australian couple had been sold by their drunken and abusive father without their mother’s knowledge for the equivalent of US$40.

India has a huge problem with orphanages crammed with genuinely unwanted children; it is estimated that there are 11 million abandoned children in the country. Last year the Indian government’s Central Adoption Resource Authority announced that it planned to make international adoption easier, especially for British parents.

But it is those children who have been taken from loving homes without the consent of their parents that is causing the concern. Last week, Dan Toole, the South Asia regional director of UNICEF, said he believed the UK was one of the main destination countries, a view supported by India’s National Center for Missing Children.

“In India you also have children being trafficked to Europe, to the USA, to the Far East, primarily for labor and sexual exploitation,” Toole said.

International adoption was also a serious problem, he added, though researchers were hampered by a lack of official statistics.

Asked if some of those offered for adoption ultimately ended up in the UK, he replied: “I would guess so but we don’t have numbers on them. I know international adoptions are happening in India. [Parents] come from almost every Western nation.”

Anuj Bhargava, managing trustee of the National Center for Missing Children, said that in most cases of international adoption, parents were unaware of what had happened.

Referring to international adoption in general, he said: “In a lot of cases, children are being sent to foreign countries. We have been contacted by children who have been kidnapped in India and adopted through an orphanage by foreign parents.”

By the time the children were old enough to explain what had happened, it was too late, he said.

“A lot of cases of this type are happening. I believe people from abroad pay a lot of money to get the child adopted,” he said.

For the families whose children are snatched to meet this demand, the heartache is unbearable. Many search for years in the hope of finding their children again.

Sitting in a small room in the village of Neb Sarai in south Delhi, Sunita stares at the picture of Rajesh. She is a small woman, dressed in a black sari decorated in red and orange detail. She is unwell today, because yesterday she walked 13km to the satellite city of Gurgaon in the baking sun looking for her boy. Rajesh, who was mute because of a birth defect, disappeared on April 26 last year.

Sunita has two daughters aged four and five, but Rajesh was her only son.

“I spend most of my time crying,” she says, dabbing again at her tears.

Rajesh had left the house at 10am. When he had not come back by 1pm, she started worrying. He had only drunk a small cup of tea in the morning, and would be hungry.

“I started searching for him with my friends. Late at night, about midnight, I went to the police to file a report. They wrote it down but when I went back again the next day they threatened to slap me if I bothered them again,” she said.

“The police said it was their responsibility to file a report and that was where their job ended. They said it was my responsibility to find him. I was so terrified that I would be thrashed that I did not go again,” she said.

Instead, she started to search the city, and never stopped.

“I only knew that he may have been kidnapped. I don’t know why someone would take him. He used to smile a lot, that’s what I remember whenever I am going to sleep. I can see his smile. But no one cares about it. No one will listen. Whenever I prepare food for my girls I think of him and how he would have enjoyed the meal too and now I don’t enjoy cooking any more,” she said.

New Delhi has the second-highest official abduction rate in India after Kolkata. The Nav Shristi (New Birth) organization helps parents in the Neb Sarai area of the city whose children have disappeared. It has a long list of children on its books, some missing for years. It produces plastic-wrapped cards for them to show to people; a photograph, the child’s name and the date reported missing. Its files contain reports on each case, sad little typed form letters with the name of the missing child inked in and a picture pinned to one corner of the sheet.

“I am the father/mother/guardian of Sanjay missing since 02/06/05,” one reads. “I did my best to locate him/her but failed. I have tried to lodge my complaint in Sangam Vihar police station but deliberately the officer in charge of said police station declined to entertain my complaint.”

Vikas was 10 when he vanished seven years ago. His black and white picture shows a small boy with big eyes. One of a family of three boys and two girls, he had been doing well at school, especially mathematics, but classes had broken up for the summer.

His mother, Kamini, remembered him running off with his friends to play. She hasn’t seen him since.

“He went to the playground with his friends at about 6am, but he did not come back. His friends said he was playing with them and then they noticed he was not there. They began searching for him but couldn’t find him. He must have been abducted,” she said.

The police took their report and said they would call if they heard anything, but seven years later, the call has never come.

“My friends said he would be fine and that one day he would come home, but he has not. For the first three or four years I spent every penny on searching for him. I searched the whole of Delhi. Once a year I go to my home in Bihar to look for him and whenever a lead comes up, I go,” she said.

Anuradha Maharishi, from the child charity Bal Raksha (formerly a branch of Save the Children) said children from the poorest areas were the most common targets.

“Sometimes they are lured with food or told they will have a better life and they come voluntarily,” she said. “Children say they have been given a sedative injection and they wake up and find they are in a railway station and if they make a sound they are burned with cigarettes.”

She said changes to the adoption laws had made it likely that more children would go abroad.

“There is a business of taking children and putting them up for adoption,” she said. “It is a big, big issue. What people think of as legitimate adoption agencies are actually stealing them and selling these children to desperate parents.”

But for parents of the children who are taken, it is often too late.

“It is true: Missing is worse than death,” Anuj Bhargava said. “If a child dies, the parents know they are gone, but if they are missing, they die every day.”

US President Donald Trump has gotten off to a head-spinning start in his foreign policy. He has pressured Denmark to cede Greenland to the United States, threatened to take over the Panama Canal, urged Canada to become the 51st US state, unilaterally renamed the Gulf of Mexico to “the Gulf of America” and announced plans for the United States to annex and administer Gaza. He has imposed and then suspended 25 percent tariffs on Canada and Mexico for their roles in the flow of fentanyl into the United States, while at the same time increasing tariffs on China by 10

Trying to force a partnership between Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) and Intel Corp would be a wildly complex ordeal. Already, the reported request from the Trump administration for TSMC to take a controlling stake in Intel’s US factories is facing valid questions about feasibility from all sides. Washington would likely not support a foreign company operating Intel’s domestic factories, Reuters reported — just look at how that is going over in the steel sector. Meanwhile, many in Taiwan are concerned about the company being forced to transfer its bleeding-edge tech capabilities and give up its strategic advantage. This is especially

US President Donald Trump last week announced plans to impose reciprocal tariffs on eight countries. As Taiwan, a key hub for semiconductor manufacturing, is among them, the policy would significantly affect the country. In response, Minister of Economic Affairs J.W. Kuo (郭智輝) dispatched two officials to the US for negotiations, and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC) board of directors convened its first-ever meeting in the US. Those developments highlight how the US’ unstable trade policies are posing a growing threat to Taiwan. Can the US truly gain an advantage in chip manufacturing by reversing trade liberalization? Is it realistic to

Last week, 24 Republican representatives in the US Congress proposed a resolution calling for US President Donald Trump’s administration to abandon the US’ “one China” policy, calling it outdated, counterproductive and not reflective of reality, and to restore official diplomatic relations with Taiwan, enter bilateral free-trade agreement negotiations and support its entry into international organizations. That is an exciting and inspiring development. To help the US government and other nations further understand that Taiwan is not a part of China, that those “one China” policies are contrary to the fact that the two countries across the Taiwan Strait are independent and