Eagerly they came — the young, the ambitious, the smartest of the smart. They lined up impatiently and crowded into the rafters above Charlie’s Cafe at the “Googleplex,” the curving glass and steel cathedral of the Internet age. Finally, laptops snapped shut and the room hushed. It was time for US Senator Barack Obama to preach to the converted.

“There is something improbable about this gathering,” the presidential hopeful said, gazing around a sea of T-shirts at Google’s Californian headquarters. “What we share is a belief in changing the world from the bottom up.”

It was last November and Obama was asked whether he lacked political experience. He compared himself with the founders of Google, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, who a decade ago were university students with a big dream.

“I suppose Sergey and Larry did not have a lot of experience starting a Fortune 100 company,” he said.

The rock star of US politics resonates at Google.

“He’s fresh, he’s new. There’s something about him that’s Google-like,” said Nicole Resz, a 26-year-old Google employee.

He was also the seventh presidential candidate to visit the company, following senators John McCain and Hillary Rodham Clinton, each seemingly determined to prove they had achieved that summit of modern aspiration — to be “Google-like.”

Can anyone become president of the US without the patronage of Google? It was once a ridiculous question, but not any more. The fastest growing company in history is also arguably the most powerful. It has the potential to reach into every corner of our lives, from the way we get news, watch entertainment and do our jobs to the way we communicate, seek information and comprehend the world. Its clean white homepage and breezy colorful logo have become so embedded in our psyches that we “google” without thinking (and use “google” as a verb). I think, therefore I google.

Ten years ago next month, in an innocuous suburban garage, Page and Brin, two geeky students at Stanford University, founded a company called Google. They would go on to create what is regularly voted the world’s top brand, earn accolades as the world’s best employers and become billionaires many times over.

They would also, say their critics, cut a swathe through the laws of copyright, threaten to devour media like a “digital Murdoch” and harvest more of our secrets than any totalitarian government — smashing the core certainties of advertising executives, book publishers, newspaper owners, television moguls and civil libertarians.

Brin and Page’s mission is to “organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” They are doing it every minute of every day in indexed Web searches, in blogs, in books, in e-mail, in maps, in news, in photos, in videos, in their own encyclopedia.

They have built a giant electronic brain made up of farms of computer servers connected around the world, a brain that learns and gains intelligence every time someone uses Google.

It is the stuff of science fiction and it all happened so fast that no one could quite grasp it, still less try to stop it. Now all of us, from the farmer in Africa switching on his first Internet connection to the next president of the US, are learning to live in a Google world. It is conceivable that future historians will regard the first day of Google Inc on Sept. 7, 1998, and not Sept. 11, 2001, as the true dawn of the 21st century.

“I don’t think it’s possible to exaggerate the significance of this thing,” said Andrew Keen, a British-born author and entrepreneur in California’s Silicon Valley.

“Every time I think of it, I’m amazed at every level. They’re absolutely in the business of revolutionizing the nature of knowledge; search has become integral in the way we think and act. In 50 or 100 years’ time, when the real histories get written of the Internet, it will start with those two boys at Stanford,” he said.

But Keen has a warning about the gatekeepers of cyberspace: “They have amassed more information about people in 10 years than all the governments of the world put together. They make the Stasi and the KGB look like the innocent old granny next door. This is of immense significance. If someone evil took them over, they could easily become Big Brother.”

Google’s recent acquisition of an online advertising company called DoubleClick set alarm bells ringing. There were objections that it would give the company a near monopoly of the online ad market, widening its scope to collect users’ personal data, but Google’s powerful lobbyists helped ensure the deal was cleared by regulators in the US and Europe. Politicians, such as Democratic Senator Herb Kohl, have belatedly started to ask whether is it growing too fast too soon. Last week the US House of Representatives’ Committee on Energy and Commerce heard evidence of how Google and other companies track users’ Web surfing behavior.

Search engines are probably more important than ever to navigate the hyper-inflating Internet: Google recently catalogued its trillionth Web page. The company does not dominate in every country, notably China, but has just improved its share of the US market to 70 percent. The technical wizardry surging through its colossal data centers to deliver instant results, however, only goes halfway to explaining how this altruistic start-up came to be seen as a corporate Death Star.

From the beginning Page and Brin wanted to make information available for free and did not care much for business. They were backed by investment capital for the first three years and made virtually no profit. It was only when Google started placing relevant ads beside its search results, and on other Web sites, that dollars came pouring in by the million and billion. It was a model that redefined the way business is done on the Web for all sorts of participants: Build traffic by giving content away for free, then make money from advertising. The formula is said to account for 99 percent of Google’s annual revenue of US$16.6 billion and profits of US$4.2 billion.

The change has rattled old certainties and some producers of content have cried foul. They accuse Google of infringing copyright by using material without their permission or failing to give them a fair share of the profits. The debate will only intensify as eyeballs turn away from TV and newspapers towards computer screens, where Google has an estimated two-thirds market share. Yet the company has also begun using its expertise to sell ads in the old media of newspapers, radio and TV.

Furthermore, when Google said all the world’s information, it really meant all. Google News, launched in 2002, aggregates breaking stories from traditional media sources around the world. Newspapers complain that their hard-won exclusives are being hijacked to boost Google’s profits. A group of Belgian papers successfully argued in court that Google stored their content without paying or asking permission and are now seeking damages of US$73 million.

In 2004 Google announced partnerships with leading libraries and universities to scan digitally millions of books from their collections. Today a visitor to Google Book Search can read on screen or download the full text of Oliver Twist, The Wealth of Nations or innumerable other out-of-copyright titles. A search will also bring up parts of books still in copyright.

Google Maps and Google Earth, launched in 2005, offer an astonishing interactive map of the planet, stitched together from aerial and satellite footage licensed from NASA and private companies. Google Street View, released in the US last year, takes this a step further by providing photographs taken at eye level, which has prompted media alarm about invasion of privacy; Google insists the UK version, yet to launch, will obscure faces and license plates.

But it was Google’s acquisition in 2006 of YouTube, the popular video sharing site, that caught most attention as a disrupter of the old media landscape. Its willingness to let people post and watch video clips for free has panicked the TV and film industries and provoked a US$1 billion lawsuit from the US entertainment group Viacom for “massive copyright infringement.”

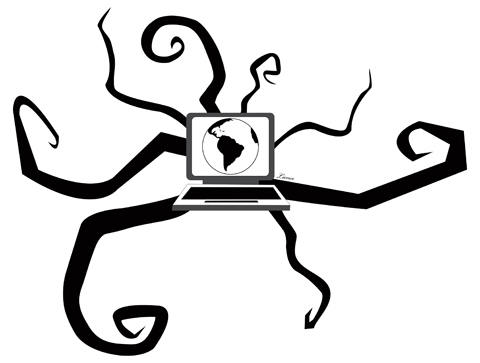

Google’s tentacles are everywhere. It runs services for blogging, e-mail, instant messaging, shopping and social networking. It offers a suite of word processing, spreadsheet and other tools to rival Microsoft’s products in the workplace. It is building a software platform for mobile phones that may challenge Apple’s iPhone and others. It has just launched Knol, a peer-reviewed encyclopedia to take on Wikipedia. In the US, Google Health enables users to maintain their own medical records. The company is also working on language translation, speech recognition and video search. Brin and Page even have their eyes on space: they have offered a US$20 million prize to anyone who can make a privately financed spacecraft able to land on the moon.

Could this be too much responsibility for any single institution, let alone a multinational corporation? Google’s informal motto, “Don’t be evil,” is put to the test every day.

An entity born in the laid-back utopianism of northern California now finds itself a US$157 billion global business empire, chasing profits, fighting or gobbling up competitors, blowing old business models away like matchsticks. And just as coal, steel and oil barons were once courted by politicians, today it is the turn of the masters of information. There is a political love affair going on with Google that both reflects and reinforces its position at front and center of world affairs.

Shortly after Obama’s pilgrimage to the “Googleplex,” it was the turn of British Conservative leader David Cameron. Cameron was accompanied there by Steve Hilton, his director of strategy, who has since moved permanently to California with his wife, Rachel Whetstone, Google’s vice-president of global communications and public affairs (she is also godmother to Cameron’s eldest son, Ivan).

Andrew Orlowski, executive editor of the technology Web site The Register, says: “The Web is a secular religion at the moment and politicians go to pray at events like the Google Zeitgeist conference. Any politician who wants to brand himself as a forward-looking person will get himself photographed with the Google boys.”

Washington is also keen to bathe in Google’s golden light. Former US vice president Al Gore, is a long-time senior adviser at the company. Obama has been taking economic advice from Google chief executive officer Eric Schmidt and received generous donations from Google and its staff. Google will be omnipresent at the Democratic and Republican national conventions, providing software for delegates such as calendars, email and graphics.

“Google has moved into the political world this year,” says its director of policy communications, Bob Boorstin, a former member of the Clinton administration.

Google’s staff in Washington include five lobbyists, among them Pablo Chavez, former general counsel for Senator John McCain. This year Google moved into new 2,508m2 headquarters in one of Washington’s most fashionable, eco-friendly buildings. Visiting senators and congressmen can now share in the famed “googly” experience of free gourmet lunches, giant plasma screens and a game room, named “Camp David,” stocked with an Xbox 360 and ping-pong.

None of this much impressed Jeff Chester, the executive director of the small but influential Center for Digital Democracy, when he was invited there.

“It puts all the other lobbying operations to shame,” he said. “They invite politicians into their Washington HQ to give advice on using Google to win re-election. It is the darling of the Democratic Party and there’s no doubt that a win by Obama will strengthen Google’s position in Washington.”

Boorstin dismisses the claims, pointing out that rivals such as Microsoft, AT&T and Verizon spend far more on lobbying and have been doing so much longer.

“It’s a statement I find both funny and pathetic,” he said.

Chester, however, is an outspoken critic on a crusade.

“Google have been very hypocritical. They try to place a digital halo around their activities. They should be at the forefront of acknowledging that these are the most powerful marketing tools around and there should be safeguards in place. Google claims it’s there to provide information but it’s really there to collect data and provide advertising, and they simply can’t own up to it,” he said.

These concerns do not apply to the US alone. As chairman of the British parliament’s Culture, Media and Sport Committee, John Whittingdale has repeatedly clashed with Google, including over whether YouTube should do more to block offensive content.

“There’s no doubt they are extraordinarily powerful,” he said. “There is concern about their dominance in online advertising. When someone is in such a strong position, you have to at least look at it. There is also the issue of behaviorally targeted advertising [the supply of ads deemed relevant based on the user’s browsing history] which needs a code of conduct.”

Like others before him, Whittingdale was struck by the peculiarity of Google’s internal culture when he visited the Californian headquarters.

“It’s a bit like a cross between The Stepford Wives and Logan’s Run: Lots of happy people in shorts always smiling, and nobody over 40. All these bright young graduates playing softball in grounds while having great thoughts,” he said.

Google’s laid-back ambience is credited as a key part of its success. Free perks for staff include three healthy meals a day, massages and laundry services as well as an on-site gym and swimming pool. Casually dressed engineers are often seen playing pool, volleyball or roller hockey, or sprawling on multi-colored beanbags.

Despite its environmental projects and its philanthropic arm, the perception of Google is slowly morphing from plucky David to sinister Goliath. In the words of former Intel chief executive Andy Grove, it is increasingly seen as a company “on steroids, with a finger in every industry.” From a garage in suburbia, they are saying, came the company that ate the world.

This is part one of a two-part series. Part two will run tomorrow.

Google by numbers

Googol — Mathematical term for the figure 1 followed by a hundred zeros, after which Sergey Brin and Larry Page named their company (complete with spelling mistake).

4 — Number of people in the firm when it started (in a Menlo Park, California, garage in September 1998).

19,604 — Number of “Googlers” (employees) worldwide, many of whom work at the “Googleplex,” the kooky HQ in Santa Clara, California.

70:30 — Ratio of male to female employees.

60% — Proportion of worldwide Internet searches made on Google.

25,000 — Number of Web pages indexed by Google early on; today it’s in the billions. Each time the company catalogues the Web, the index grows by 10 percent to 25 percent.

US$0.00 — Amount it costs Google staff to eat (breakfast, lunch and dinner are free).

US$157 billion — Google’s current market value.

40% — Proportion of online advertising controlled by Google.

1 day per week — Google engineers are encouraged to spend on other projects that interest them. Google News is said to have resulted from this policy.

112 — Number of languages Google “speaks,” allowing users to set their homepage to Latin and, of course, Klingon.

1 million+ — Number of resumes sent to Google every year from would-be employees.

Monday was the 37th anniversary of former president Chiang Ching-kuo’s (蔣經國) death. Chiang — a son of former president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石), who had implemented party-state rule and martial law in Taiwan — has a complicated legacy. Whether one looks at his time in power in a positive or negative light depends very much on who they are, and what their relationship with the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) is. Although toward the end of his life Chiang Ching-kuo lifted martial law and steered Taiwan onto the path of democratization, these changes were forced upon him by internal and external pressures,

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) caucus whip Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) has caused havoc with his attempts to overturn the democratic and constitutional order in the legislature. If we look at this devolution from the context of a transition to democracy from authoritarianism in a culturally Chinese sense — that of zhonghua (中華) — then we are playing witness to a servile spirit from a millennia-old form of totalitarianism that is intent on damaging the nation’s hard-won democracy. This servile spirit is ingrained in Chinese culture. About a century ago, Chinese satirist and author Lu Xun (魯迅) saw through the servile nature of

In their New York Times bestseller How Democracies Die, Harvard political scientists Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt said that democracies today “may die at the hands not of generals but of elected leaders. Many government efforts to subvert democracy are ‘legal,’ in the sense that they are approved by the legislature or accepted by the courts. They may even be portrayed as efforts to improve democracy — making the judiciary more efficient, combating corruption, or cleaning up the electoral process.” Moreover, the two authors observe that those who denounce such legal threats to democracy are often “dismissed as exaggerating or

The National Development Council (NDC) on Wednesday last week launched a six-month “digital nomad visitor visa” program, the Central News Agency (CNA) reported on Monday. The new visa is for foreign nationals from Taiwan’s list of visa-exempt countries who meet financial eligibility criteria and provide proof of work contracts, but it is not clear how it differs from other visitor visas for nationals of those countries, CNA wrote. The NDC last year said that it hoped to attract 100,000 “digital nomads,” according to the report. Interest in working remotely from abroad has significantly increased in recent years following improvements in