Behind the hills and the skyscrapers the sun is going down on another working day, but Ren Zhirong cannot stop to talk. The carpet still has to be laid on the university’s volleyball courts, the spotlights connected, the music chosen. Only then can scores of his finest pupils show Yanan, a small town in central China, “what ballroom dancing is all about.”

“This is the moment I have been working towards all my life,” said Ren, 48, as he watched 100 contestants, all from Yanan University, putting the finishing touches to their make-up and costumes. “This is my dream.”

The couples adjusting pink nylon gowns and sequined electric blue trousers do not know it but they — and Ren — are the face of modern China. Far from Beijing, from Shanghai or from the bustling economic powerhouse of Guangdong Province, they have grown up in a poor, rural, northern-central province and are often the first in the family to receive more than a rudimentary education — and in some cases the first not to worry about basics like food and a roof.

Shi Taojao, in a yellow dress, hopes for a career in “international tourist management.” Dancing allows her “to meet boys.” These young people have watched their country evolving at an astonishing pace. In the last competition, Shi came second. Now she wants to be first.

Ren himself knows about change. He set up the club, from which he now earns a good living, with the 60,000 yuan (US$8,800) redundancy payment he received when the state-owned factory where he had worked for 26 years shut 18 months ago — bankrupted by the government’s free market reforms.

“Once it was just two of us. Now we have 400 dancers,” said Ren, a former truck driver.

And with three weeks to go until the Olympics, Ren’s ambitions of teaching all Yanan the cha-cha-cha have met with official approval.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is nothing if not flexible. What some might once have considered a bourgeois Western import has been cleverly co-opted.

“We are using ballroom dancing to mobilize young people for the Olympics,” said Shen Changliang, in Yanan’s public sports office.

As elsewhere in China, local authorities are planning a series of sporting competitions, parades and open days to crank up the popular fervor for the Olympics.

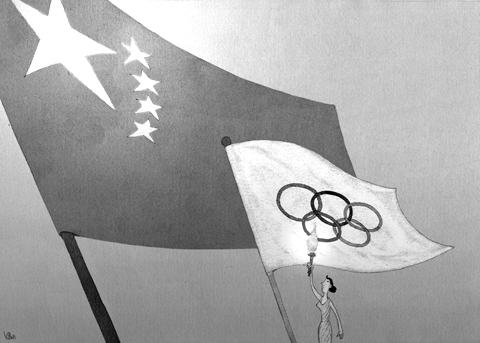

Sports authorities may insist that the Games themselves are non-political, but few in China are blind to their internal significance. Bringing the Olympics to the country is widely seen as a vindication of the government’s diplomatic skill — and therefore that of the party — as well as its economic competence. It is also seen as a key assertion of a new national identity and confidence.

“Sport is a key part of the project of the party for the nation,” said Liu Haijun, director of the Yanan Sports Institute.

So Yanan, population 340,000, now has a new 20,000-seat sports stadium, one of hundreds of such projects across the country. Every afternoon, after lessons in the morning, scores of teenage students train on the stadium’s Astroturf. Mainly from poor rural families, they are all students of Yanan’s subsidized Sports Institute. This, they hope, is their way out of poverty.

But equality, sporting or otherwise, is relative. The director’s large, new black car is parked outside the students’ squalid, rudimentary accommodation and the windows to his air-conditioned office keep the stench from the students’ communal latrines at bay.

For the government, sport not only projects national pride and prowess, but is a way of cushioning the pain of immense social and economic changes.

The parents of Lu Fan, 17, an aspiring young sprinter at the academy, live 48km north of Yanan in an apartment provided by the factory where they have worked for 20 years. If the state-owned enterprise closes they will lose income, healthcare and their home. Then the 5,500 yuan per year fees for the sports institute would be very difficult to find.

“I am always anxious,” said Lu’s mother, Li Chunmei. “But my son has talent, so I am hopeful too.”

Lu said he is “realistic.”

“I don’t dream of the Olympics. But maybe I’ll make it on the national stage one day. And I’ll make a good living too,” he said

But sport will only go so far in uniting the nation behind a repressive one-party state ... and the government has other cards to play.

Yanan is the city where Mao Zedong (毛澤東) ended the Long March and built up his forces before finally launching the campaign that brought him and the resurgent CCP to power in 1949. Scattered among the towering new apartment blocks are the simple — but perfectly maintained — huts and halls used by Mao and his comrades more than 60 years ago.

Since 2005, the government has poured huge resources into “red tourism” here. A vast station is under construction in Yanan to welcome special trains ferrying visitors from the sprawling coastal cities. The prettiest and brightest local girls are recruited to guide half a million visitors each year.

“The important thing is to transfer the spirit, diligence and patriotism of the old generation,” said Yuan Xin, 23, a guide and local student.

The visitors are mainly on coach trips from factories and schools but increasingly there are individual visitors, too. In the courtyard of Chairman Mao’s former home, one woman said she had brought her nine-year-old daughter to learn of “the sacrifices made by our leaders.” In another, two young boys dressed up as 1930s soldiers and took pictures of each other.

“The hardship the old leaders suffered is really impressive,” one said.

For their guide, there was no doubt.

“The Communist Party and the Chinese nation are inseparable. Without the Communist Party, there is no new China,” she said.

The success of “red tourism” reveals one reason for the party’s continued hold on China: the legitimacy the party has as a liberator of the country from invaders, colonial proxies and powers in the mid-20th century.

Equally important is a reputation for efficient management, which explains in part why such extraordinary precautions are being taken to ensure a trouble-free Olympics — despite the bad press they provoke overseas. For months, visas have been restricted, dissidents harassed, activists gagged, normally tolerated critics warned to stay silent and even the most innocent tourists vetted.

“If imposing the control of the party on the Games means less visitors, so be it,” one Western diplomat said. “As long as the Games are without incident, anything is acceptable.”

Few in Yanan, or elsewhere in China, mention democracy or human rights. Some are too frightened. For others, perhaps conditioned by 60 years of tightly controlled media, such ideas seem alien.

“China? Democratic? What a funny idea!” one Yanan housewife said.

Others repeat the government’s argument that China is too big and unstable for Western-style democracy to work.

Among the scores of people interviewed by this reporter in Yanan only one, a Christian woman student from the Mongolian minority, expressed a desire for greater democracy because “people would then be more free to practice their religion.” She was quick to add that Chinese President Hu Jintao (胡錦濤) and Premier Wen Jiabao (溫家寶) were the best leaders in 40 years.

The CCP is far from a tiny elite, as some commentators claim. Its official membership is 73 million and growing. Its members range from the powerful technocrats in the upper reaches of government to village chairmen. They include committed socialists, bureaucrats of every variety, quality, honesty and competence and, increasingly, ambitious young networkers.

Yet “socialism” appears as something of a relic in the new China and “communism” an inherited but empty title. Few states have embraced neo-liberal capitalism so quickly, so enthusiastically and so thoroughly. Decades of economic growth appear to vindicate the choices made by party leaders in the early 1980s and during a second wave of economic restructuring a decade later.

Alongside the legitimacy conferred by their forebears (the famines and brutality of the Mao era are carefully obscured) and the loyalty resulting from decades of social engineering, is the party’s trump card: economic development. And in Yanan, though perhaps less spectacularly than in Shanghai, the new wealth is very evident.

Outside a small rustic restaurant a new Jaguar belonging to businessman Wang Cheng, 45, is parked.

“It cost me 1.5 million yuan,” he said, tucking into a meal of pork intestines and chilli. “I have one philosophy in life: A man’s worth is his wealth, his value is his riches.”

Wang, a property developer, hotelier and son of a government clerk and a farmer, is not a party member. “That does not mean I am not a patriot,” he said.

At the university, staff are proud that the car park is full.

“Now we have more than 80 cars for 270 staff. Ten years ago there were none,” one lecturer said.

Even menial laborers living 18 to a filthy “cave” house on the slopes around Yanan insisted that life was “much better” — though they complained about rising prices, the cost of healthcare and school fees. And a 61-year-old woman who earns 13 yuan each evening from collecting plastic bottles for recycling said that life was easier, at least compared with the grim days of famine and political brutality of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution of 1966 to 1976.

Drive off the new motorway running down the fertile valley and on to the rutted road that leads east from Yanan into the hills and, for 190km, the landscape does not vary: wooded hills fissured by erosion; small ponds staked with fish nets; terraced fields sparsely planted with wheat; and villages, a hundred identical dusty clusters of brick, concrete, peeling paint, fading slogans and chickens. On the final ridge before the Yellow river gorge, Wang Zhihong, 44, is tending his apple trees.

Wang’s village, Zaho, is a long way from the sparkling image of the new China that the government hopes to showcase during the Olympics. Wang admits that, like most of his neighbors, he eats meat only about a dozen times a year. Jars beside his earth-and-brick house collect rain from the roof for drinking and washing. Though some villages have mains water, Zaho’s 280 inhabitants cannot find the 300 yuan for each connection. Most young people have gone to work in the cities.

The daughters of Wang Cui, 51, are in Beijing.

“What do you expect?” she said. “This place has not changed for 30 years.”

Even the new house she has built with cash sent by her children brings worries.

“Now all our poor relatives want to borrow money,” she said.

But however much Zaho’s villagers complain — about poor healthcare, the distant school, corruption and partisan local officials — they remain loyal “to the great project of building a new China,” as described in the slogans painted on their walls a year or so ago. They are grateful for recent tax cuts for farmers and proud that their country is hosting the Olympics. There is only a trace of nostalgia.

“In the old days, 30 years ago,” Wang said. “Everyone was poor and life was tough ... but at least we were all equal.”

Down in the gorge that funnels the Yellow river through the mountains on its way to the plains and the sea, a crowd of tourists — all Chinese — take photographs. The Games, the Chinese authoritarian model, the Western statements on Tibet, their country’s economic success, all combine in an outpouring of identity and emotion, of pride in their nation, “their” Olympics and their government.

There are, of course, threats to the party’s dominant position that could become serious in the decades to come: the global economic factors and local environmental problems could derail the economic growth that so many believe will bring them or their children wealth. It is clear that the “rush for growth” is leading to such profound inequality that stability could be threatened. In one shop in Yanan, where five pairs of Italian-made shoes, each costing what the staff earn in a month, are sold each day, there were rumblings of discontent.

“It does make me angry,” whispered one shop assistant. “The gap between the rich and the poor is getting too big.”

The real trouble for the ruling party may come not from this generation but the one that follows. But that is some time away yet. For now, in Yanan and the rest of China, the dance into a capitalist future goes on and the Communist Party continues to call the tune.

Yanan: Cradle of revolution

Population of Yanan: 340,000.

Area: 3,541km2.

Formerly known as Yanzhou, city records go back 1,400 years.

The town was used as a military headquarters during the second Sino-Japanese war (1937-1945) and China’s civil war (1927-1949) between the communists and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) led by Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石).

When the town was razed by Japanese bombing during the World War II, Yanan’s inhabitants took to living in yaodong, artificial caves carved into the surrounding hillsides.

Yanan was the end point of the Long March trek of the Red Army to escape attacks from the KMT armies. It began in October 1934.

It is the location of the general offices of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party.

The town was the venue for meetings and interviewsA between the communist leader, Mao Zedong, and the US journalist and author Edgar Snow, as well as his fellow US journalist, Anna Louise Strong, who was a communist supporter.

The town contains 140 sites that are regarded as significant in revolutionary history, such as the Wangjiaping site, the Yangjialing site, the Date garden and Pagoda Hill.

The Hukou waterfall nearby is the only Yellow River waterfall and the second-biggest waterfall in China.

The town that provided a refuge for Mao’s dream

The Long March finished in a small, simple, brick-and-mud home with basic furnishing in central Yanan. It had started almost exactly a year earlier, in 1934, when Mao Zedong and a clutch of other Chinese Communist leaders set out from southeastern Jiangxi Province with more than 100,000 men to escape the stranglehold that the powerful KMT armies had on their weakened forces.

They marched west and then north across thousands of kilometers of tough countryside and turned defeat into a stunning victory, establishing Mao’s hold on the fractious Communist Party and allowing a respite for him to develop a coherent ideology and build support among the crucial rural masses. Whether it covered 5,600km, as Western revisionist historians claim, or 12,900km, as officially maintained, the Long March was an epic. Only a tenth of those who started the trek reached its end. In one battle, 40,000 died. When Mao’s wife gave birth, the child was abandoned.

The symbolism of the Long March escaped no one, even at the time. In 1935 Mao wrote in typically blunt fashion: “The Long March is a manifesto. It has proclaimed to the world that the Red Army is an army of heroes, while the imperialists and their running dogs ... are impotent. The Long March is also a propaganda force. It has announced ... that the road of the Red Army is [the] only road to liberation.”

From their sanctuary in Yanan, the Communists launched their victorious campaign in the chaotic aftermath of World War II and the Japanese occupation. Mao held power, with brutal efficacy, from 1949 until his death in 1976.

The gutting of Voice of America (VOA) and Radio Free Asia (RFA) by US President Donald Trump’s administration poses a serious threat to the global voice of freedom, particularly for those living under authoritarian regimes such as China. The US — hailed as the model of liberal democracy — has the moral responsibility to uphold the values it champions. In undermining these institutions, the US risks diminishing its “soft power,” a pivotal pillar of its global influence. VOA Tibetan and RFA Tibetan played an enormous role in promoting the strong image of the US in and outside Tibet. On VOA Tibetan,

Sung Chien-liang (宋建樑), the leader of the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) efforts to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) Legislator Lee Kun-cheng (李坤城), caused a national outrage and drew diplomatic condemnation on Tuesday after he arrived at the New Taipei City District Prosecutors’ Office dressed in a Nazi uniform. Sung performed a Nazi salute and carried a copy of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf as he arrived to be questioned over allegations of signature forgery in the recall petition. The KMT’s response to the incident has shown a striking lack of contrition and decency. Rather than apologizing and distancing itself from Sung’s actions,

US President Trump weighed into the state of America’s semiconductor manufacturing when he declared, “They [Taiwan] stole it from us. They took it from us, and I don’t blame them. I give them credit.” At a prior White House event President Trump hosted TSMC chairman C.C. Wei (魏哲家), head of the world’s largest and most advanced chip manufacturer, to announce a commitment to invest US$100 billion in America. The president then shifted his previously critical rhetoric on Taiwan and put off tariffs on its chips. Now we learn that the Trump Administration is conducting a “trade investigation” on semiconductors which

By now, most of Taiwan has heard Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an’s (蔣萬安) threats to initiate a vote of no confidence against the Cabinet. His rationale is that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP)-led government’s investigation into alleged signature forgery in the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) recall campaign constitutes “political persecution.” I sincerely hope he goes through with it. The opposition currently holds a majority in the Legislative Yuan, so the initiation of a no-confidence motion and its passage should be entirely within reach. If Chiang truly believes that the government is overreaching, abusing its power and targeting political opponents — then