It is now clear that microfinance can help lift people out of poverty. Millions of lives across South Asia, Africa, Latin America and Eastern Europe have been transformed through small loans provided by microfinance institutions with the backing of social organizations and international aid agencies.

The movement has attracted so much attention that one of its pioneers, Grameen Bank, along with its founder Muhammad Yunus, has been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 for its work in rural Bangladesh since the 1970s.

The more relevant question then is how to assimilate microfinance within the mainstream of international finance? How can commercial banks, insurance companies and international financial institutions work with microfinance institutions (MFIs) to increase financial services to the poor?

As we know, microfinance is the process of providing a range of financial services, including small-denomination loans without collaterals, to people who otherwise have no access to modern financial institutions, enabling them to pull themselves out of poverty.

It provides the poor with an opportunity to grow their enterprises, increase income, pay for emergencies and invest in the health and education of their families.

Bangladesh is one of the notable success stories of microfinance. There, loans are typically provided to a peer group, instead of to individuals. The peer pressure among the borrowers, who act as co-guarantors for each other, ensures a high rate of recovery of the loans, often as high as 100 percent, much higher than that seen in mainstream commercial banking.

Additionally, an overwhelming majority of the recipients of such loans in Bangladesh have traditionally been women who are seen as more responsible borrowers, making microfinance one of the key drivers for gender equality, social empowerment and financial inclusion.

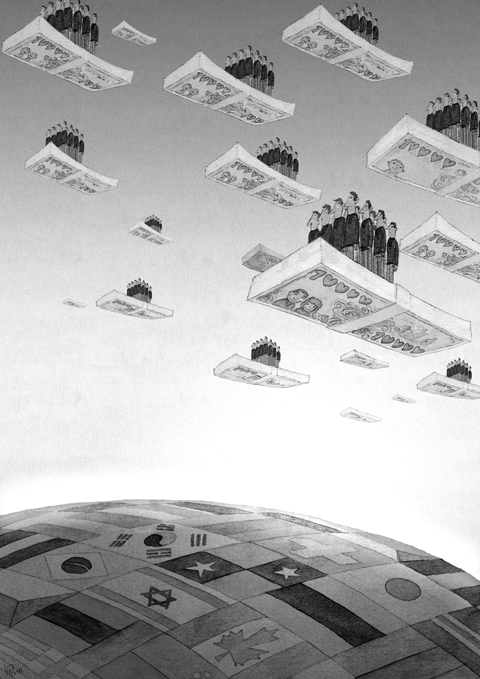

The emerging success stories have led to a growing interest in the sector, with more than $4.4 billion flowing into MFIs in 2006, up from just US$1.7 billion in 2004. The total outstanding value of microfinance loans worldwide stands at an estimated US$25 billion. South Asia alone accounts for half the global client base for microcredit.

Yet, more than 3 billion people today still lack access to any financial products or services. Therein lies an opportunity for mainstream financial services companies.

Seizing the Opportunities

Microfinance can be a powerful tool for financial services companies to bolster local economies by creating jobs, increasing skills and boosting productivity. Recent research has shown that a 10 per cent increase in private credit relative to the size of the economy can lift 3 percent of the population out of poverty.

At the same time, in an era when public companies are increasingly being measured by their “double bottom lines” of financial performance and social impact, banks and insurance companies can use the platform of microfinance to provide credit, savings, insurance and remittances, in the process expanding their reach into unbanked markets.

Thus, microfinance could be a win-win opportunity for both the local economies and the financial services industry!

Not surprisingly, funds have started to flow at a faster pace into this sector. So much so that a recent seminar on microfinance organized by Standard Chartered in New Delhi highlighted an odd problem: there are not enough investment ready MFIs and that not enough attention has been given to building sustainable institutions.

The microfinance industry remains highly concentrated, with the top 50 MFIs serving over 70 percent of all borrowers worldwide.

Banks will, for sure, face a host of challenges as they make their way into the nascent industry. For one, regulatory frameworks governing microfinance vary across regions and countries.

The geographical footprint of the industry, spanning across the underdeveloped and emerging markets, means higher political and other event risks associated with the business.

Add to that the lack of transparency among many MFIs — only a select few MFIs follow internationally recognized reporting standards, even fewer use internationally recognized auditors — and the lack of skills among the ultimate recipients of microcredit because of low financial literacy and education.

To ensure long-term viability for the industry, microfinance should be a sustainable business and not just another form of corporate responsibility enterprise. The risk-return equation must add up in the same way as it does for any other business that the banks get involved in. Moreover, social returns have to be brought into the equation while calculating the returns on investment.

Challenges

Clearly, the main task now is to build more capacity within the industry so that a larger number of MFIs can efficiently utilize the increased flow of funds. As a first step, MFIs will have to show that they are adept at managing operational and financial risks.

As the industry matures, MFIs will have to speak the language of international investors and this means greater transparency and accountability, more rigorous analysis on performance metrics and increased use of services provided by recognized auditors and ratings agencies.

Strengthening corporate governance at MFIs will also play a critical role in building investor confidence. This involves the presence of independent directors, audit committees, advisory committees — all those ingredients that help maintain a system of checks and balances.

How Banks Can Help

Large financial institutions can play a pivotal role in this exercise. Using their knowledge of emerging markets, banks can help philanthropies, charities, multilateral and bilateral aid agencies and investment funds identify robust MFI intermediaries through whom funds can be channeled gainfully.

Simultaneously, banks can assist MFIs in upgrading their skills through sharing their huge wealth of training material on credit analysis, operational risk management, process management and corporate governance and generally act as a support network that MFIs can tap into.

This is in the banks’ own interest since a more sophisticated MFI network would be better placed to utilize the full range of products and services that commercial banks offer — transaction banking, cash management, foreign exchange and other capital market services.

Indeed, some of the more mature MFIs have already started to access the debt and equity capital markets through banks as part of their efforts to diversify their funding base.

At the same time, MFIs want to use advanced banking technology such as mobile phone banking, smart cards, biometric data, voice recognition equipment and credit bureaus to expand their reach and to better manage their risks.

This process of MFIs making increasing use of capital markets, banking technology and processes needs to be encouraged because it not only engenders a wider dispersal of the risk of investing in MFIs but it also leads to more transparency and better standards of corporate governance in the industry.

Standard Chartered’s own experience in this field testifies to the fact that the challenges, though substantial, can be surmounted.

Since formulating its strategy in 2006, Standard Chartered has committed to establish a US$500 million microfinance facility over a five-year period. This facility will provide MFIs, development organizations and fund managers with credit and financial instruments as well as technical assistance. It is expected to benefit 4 million borrowers across Asia and Africa who currently have no access to financial services.

So far, the bank has provided funding of about US$180 million, supporting 48 MFI partners in 15 countries. Of the 1.2 million people Standard Chartered supported through microfinance loans last year, almost 80 percent were women. It was their first step towards financial independence.

The bank’s overall objective in partnering with MFIs is to make sure individuals, families and communities move from subsistence loans to enterprise loans, and eventually graduate to accessing formal banking services. In the process, the bank contributes to social and economic development.

Our projects range from arranging funds for BRAC in Bangladesh, the world’s largest microfinance institution, to providing a lending facility directly to cotton farmers in rural China — a first for any foreign bank in the country. Similar projects for India are on the drawing boards.

Recently, the Bank partnered with International Finance corp., a member of the World Bank Group, in the launch of the first-ever issuance of notes backed by loans to MFIs in Africa and Asia.

New products

The transaction, which made use of innovations in mainstream capital markets, established a new product to provide investors with access to microfinance as an asset class.

As part of the transaction, IFC will invest US$45 million in credit-linked notes to be issued by a special purpose vehicle set up by Standard Chartered. The notes will be linked to a portfolio of loans that the bank has made to MFIs in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

This transaction will unlock more funding for microfinance as it will enable the bank to extend additional credit to MFIs that will in turn reach more unbanked people.

It is encouraging that all these high impact initiatives are run on commercial lines. Clearly, the market opportunity is tremendous; there is a replicable and scalable business model in place; slowly, but surely, there are a growing number of robust MFI intermediaries; and, increasingly, investors see this sector as a great way to earn sustainable profits.

Our own experience makes us hopeful that, with the greater involvement of mainstream financial services institutions, the microfinance industry will be able to achieve its full potential for rebuilding economies, renewing societies and transforming lives.

Jim McCabe is president of Standard Chartered Bank (Taiwan).