It was, in more ways than one, an image pregnant with meaning. Normally a photograph of the Spanish defense minister inspecting the nation’s troops would elicit little comment beyond those with a nerdish interest in medals and battle formations. But this time the minister was Carme Chacon, a 37-year-old mother-to-be with no previous military experience.

As TV footage of the seven-months pregnant Chacon was beamed into early morning households, some of the more conservative elements of Spanish society were already choking on their breakfast churros. A leading article in El Mundo dismissed it as “political marketing,” stating that Chacon’s profile “clashes with the traditional values and culture of the Spanish army.”

Aware perhaps of the consternation she would provoke, the new minister had attempted to dress neutrally for the occasion — a tailored black jacket and a white smock-top that artfully disguised her baby bump. Yet the visual contrast between this attractive young woman, heavy with child, and the straight-backed military men standing to attention with rifles and gleaming brass buttons was undeniably striking.

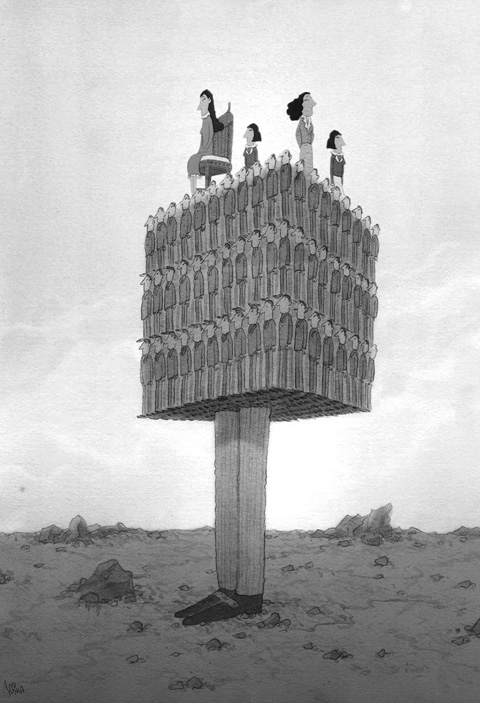

It marked a radical changing of the old guard, and from that one image a greater truth started to emerge. Chacon was one of nine women appointed last week by the Socialist Prime Minister Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero to the continent’s first female majority Cabinet. In a country still recovering from four decades of nationalist rule under General Francisco Franco — women in Spain were not allowed to have their own passports or bank accounts until after his death — Zapatero’s appointments signified a tectonic shift in social perception.

“It was a wonderful photo,” says Yvonne Galligan, director of the Center for the Advancement of Women in Politics at Queen’s University Belfast. “I am quite sure it was, to many Spaniards, an amazing sight, but you needed that media impact to unsettle the old gender order. That’s essentially what that image represented.”

Another photograph of Chacon visiting peacekeeping troops at Spain’s military base in Herat, northwest Afghanistan, on Saturday highlights the glaring juxtaposition of stereotypical male and female roles: the mother and the soldier; the protectors of the family and the protectors of the nation. She was accompanied on her trip by a medical team, including a gynecologist, and she plans to visit Spanish peacekeeping troops in Lebanon in the next few days.

Zapatero’s decision to give key roles to women is part of a broader trend. Over the past decade, Europe has seen a steady rise in the number of women in positions of political power. There are currently seven female foreign affairs ministers and, since 2000, there have been no fewer than 16 women chancellors of the exchequer. Finland and Germany have female leaders — Tarja Halonen and Angela Merkel. Sweden has adopted the unfortunately named “zipper” system, which ensures that if a man tops a party list, the second position must be occupied by a woman; in 2006, women took 164 parliamentary seats out of 349.

But while Nordic countries have long been at the vanguard of generating greater gender equality in Europe, the change has been particularly noticeable in nations that have traditionally prided themselves on their orthodox attitudes to hearth and home. In France, a country that denied women the vote until 1944, French President Nicolas Sarkozy has fulfilled an election pledge for greater parity between men and women by appointing seven women in a 15-strong Cabinet, including Minister for Justice Rachida Dati, Minister of Finance Christine Lagarde and Minister of the Interior Michele Alliot-Marie. In Italy, where prime-time television quiz shows are still presented by women wearing little more than spangly bikini bottoms and collagen-enhanced smiles, the re-elected Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi has promised that at least a third of his ministers will be women. And in Spain, a nation that provided us with the word machismo, it is now legally enshrined that no more than 60 percent of party candidates can be male.

While it might seem as though Europe has suddenly been overrun by well-groomed women who attract more attention for their handbags than their portfolios, in truth there has been a long fermentation process. Statisticians attribute the feminization of such a traditionally male-dominated environment to the socioeconomic changes that have substantially altered the demographic landscape in mainland Europe over the past decade.

Elizabeth Villagomez, a senior partner at the Almenara Economic and Social Studies Institute in Madrid, points to the lowered birth rate in Spain as an indicator that women are delaying marriage, or eschewing it altogether. Over the past two decades, there has been an 87 percent rise in the employment rate among married women and a 48 percent drop in the fertility rate (in the past five years, this has gone up slightly, a fact that Villagomez attributes to an increase in immigrant families).

“Women in this country now make up more than 50 percent of university students and they are slowly taking hold,” she says. “The marriage market is being upset by this. Even if you do have a family, wages are very low so both parents must work and that has an impact on household power structures.”

“In cohabiting professional couples across Europe, the trend is for the woman to earn more than the man. That’s also happening in the US. I think politicians are very aware that women have acquired quite a bit of education and that they cannot be kept in the home. The appointment of so many women to the Cabinet is therefore market driven,” she says.

In Italy, where the fertility rate is now one of the lowest in the West, a similar picture is emerging. In 1950 only 7 percent of 14 to 17-year-old Italian girls went to school. Now, female university students outnumber male students and 80 percent of them go into full-time employment.

Even the unenlightened Berlusconi, a man who last week criticized Zapatero for making his government “too pink,” has been forced to take note. During his re-election campaign, he promised to shower women with Cabinet jobs, somewhat ruining the effect by claiming that right- wing women were “more beautiful” than those on the left.

Of course, not everyone is tripping along in a state of emancipated bliss. In Spain one woman a week dies as a result of domestic violence. Across the board, women earn less than their male counterparts.

And, as French Minister for Health, Youth Affairs and Sport Roselyne Bachelot-Narquin said: “There’s a difference between the idea of an equality law and the application of it in practice. There’s still some way to go. Women are very under-represented.”

The political sphere remains an overwhelmingly male arena, soaked through with the sort of cigar-chomping, back-slapping testosterone one might expect to find in a Turkish hamam. On the campaign trail, the 71-year-old Berlusconi, insisted that, at 1.71m, he was taller than Sarkozy or Russian President Vladimir Putin, as if it were a matter of state importance.

Wary of their growing anachronism in an increasingly female world, it seems as though male leaders are undergoing a collective midlife crisis. Berlusconi had a hair transplant four years ago and took to sporting an ill-judged white bandana, while the current boom in French men seeking Botox injections to keep up with their younger wives has been dubbed “the Sarkozy effect.” In recent months, we have been treated to the unedifying spectacle of some of the most powerful men in the world trying to outdo each other like schoolboys comparing conker sizes. Not wishing to be outshone, Putin swiftly brought in an array of glamorous new female recruits, reportedly in a bid to “sex up” the Duma.

The new politicians included Svetlana Khorkina, a 28-year-old blonde Olympic gymnast who caused a sensation by posing nude in Playboy magazine. It seems that political power is still inextricably linked with virility, as if an excessive show of masculinity will reassure voters that the virtue of their country is being protected against the aggressive advances of a European superstate.

In the UK, the Fawcett Society, which campaigns for gender equality, has estimated that at the present rate of progress the Labour party could take another 20 years to reach a position where half its parliamentary members are women. By the same calculation, the opposition Conservatives would take 400 years.

Edwina Currie, one of the women to make it into government with the British Conservatives, remains pessimistic about the prospects for parity.

“It’s great to see the progress that women are making in countries like Spain, Italy and France, but I don’t think we’ll see the same thing happening here,” the former junior health minister says.

When Zapatero was first elected four years ago, he insisted that “the more equality women have, the fairer, more civilized and tolerant society will be.”

All of which might be true, but only if Berlusconi leaves his bandana at home. Not even the most emancipated democracy can be expected to tolerate that.

President William Lai (賴清德) attended a dinner held by the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) when representatives from the group visited Taiwan in October. In a speech at the event, Lai highlighted similarities in the geopolitical challenges faced by Israel and Taiwan, saying that the two countries “stand on the front line against authoritarianism.” Lai noted how Taiwan had “immediately condemned” the Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel by Hamas and had provided humanitarian aid. Lai was heavily criticized from some quarters for standing with AIPAC and Israel. On Nov. 4, the Taipei Times published an opinion article (“Speak out on the

Most Hong Kongers ignored the elections for its Legislative Council (LegCo) in 2021 and did so once again on Sunday. Unlike in 2021, moderate democrats who pledged their allegiance to Beijing were absent from the ballots this year. The electoral system overhaul is apparent revenge by Beijing for the democracy movement. On Sunday, the Hong Kong “patriots-only” election of the LegCo had a record-low turnout in the five geographical constituencies, with only 1.3 million people casting their ballots on the only seats that most Hong Kongers are eligible to vote for. Blank and invalid votes were up 50 percent from the previous

More than a week after Hondurans voted, the country still does not know who will be its next president. The Honduran National Electoral Council has not declared a winner, and the transmission of results has experienced repeated malfunctions that interrupted updates for almost 24 hours at times. The delay has become the second-longest post-electoral silence since the election of former Honduran president Juan Orlando Hernandez of the National Party in 2017, which was tainted by accusations of fraud. Once again, this has raised concerns among observers, civil society groups and the international community. The preliminary results remain close, but both

News about expanding security cooperation between Israel and Taiwan, including the visits of Deputy Minister of National Defense Po Horng-huei (柏鴻輝) in September and Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Francois Wu (吳志中) this month, as well as growing ties in areas such as missile defense and cybersecurity, should not be viewed as isolated events. The emphasis on missile defense, including Taiwan’s newly introduced T-Dome project, is simply the most visible sign of a deeper trend that has been taking shape quietly over the past two to three years. Taipei is seeking to expand security and defense cooperation with Israel, something officials