On the day he decided to run away, nine-year-old Coli awoke on a filthy mat.

Like a pup, he lay curled against the cold, pressed between dozens of other children sleeping head-to-toe on the concrete floor.

His T-shirt was damp with the dew that seeped through the thin walls. The older boys had yanked away the square of cloth he used to protect himself from the draft. He shivered.

It was still dark as he set out for the mouth of a freeway with the other boys, a tribe of seven, eight and nine-year-old beggars.

Coli padded barefoot between the stopped cars, his head reaching only halfway up the windows. His scrawny body disappeared under a ragged T-shirt that grazed his knees. He held up an empty tomato paste can as his begging bowl.

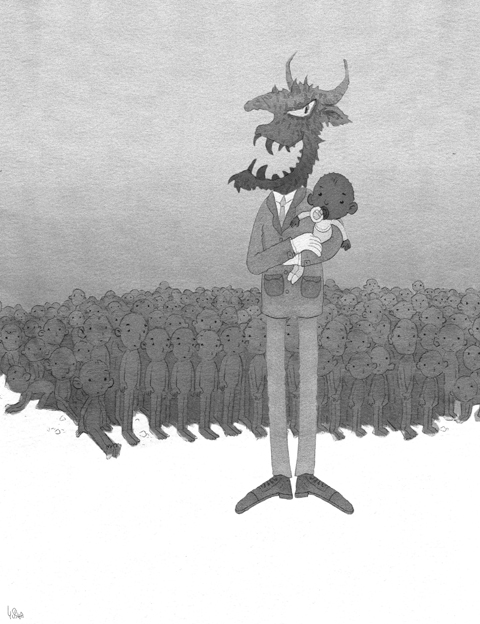

There are 1.2 million Colis in the world today, children trafficked to work for the benefit of others. Those who lure them into servitude make US$15 billion annually, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO).

It’s big business in Senegal. In the capital of Dakar alone, at least 7,600 child beggars work the streets, according to a study released in February by the ILO, the United Nations Children’s Fund and the World Bank. The children collect an average of 300 African francs (US$0.72) a day, reaping their keepers US$2 million a year.

Most of the boys — 90 percent, the study found — are sent out to beg under the cover of Islam, placing the problem at the complicated intersection of greed and tradition. For among the cruelest facts of Coli’s life is that he was not stolen from his family. He was brought to Dakar with their blessing to learn Islam’s holy book.

In the name of religion, Coli spent two hours a day memorizing verses from the Koran and over nine hours begging to pad the pockets of the man he called his teacher.

It was getting dark. Coli had less than half the amount of money he was told to bring back. He was afraid. He knew what happened to children who failed to meet their daily quotas.

They were stripped and doused in cold water. The older boys picked them up like hammocks by their ankles and wrists. Then the teacher whipped them with an electrical cord until the cord ate their skin.

Coli’s head hurt with hunger. He could already feel the slice of the wire on his back.

He slipped away, losing himself in a tide of honking cars.

Three years ago, a man wearing a skullcap came to Coli’s village in the neighboring country of Guinea-Bissau and asked for him.

Coli’s parents immediately addressed the man as “Serigne,” a term of respect for Muslim leaders on Africa’s western coast. Many poor villagers believe that giving a Muslim holy man a child to educate will gain an entire family entrance to paradise.

Since the 11th century, families have sent their sons to study at the Koranic schools that flourished on Africa’s western seaboard with the rise of Islam. It is forbidden to charge for an Islamic education, so the students, known as talibe, studied for free with their marabout, or spiritual teacher. In return, the children worked in the marabout’s fields.

The droughts of the late 1970s and 1980s forced many schools to move to cities, where their income began to revolve around begging.

Today, children continue to flock to the cities as food and work in villages run short.

Not all Koranic boarding schools force their students to beg. But for the most part, what was once an esteemed form of education has degenerated into child trafficking. Nowadays, Koranic instructors net as many children as they can to increase their daily take.

“If you do the math, you’ll find that these people are earning more than a government functionary,” said Souleymane Bachir Diagne, an Islamic scholar at Columbia University. “It’s why the phenomenon is so hard to eradicate.”

Middlemen trawl for children as far afield as the dunes of Mauritania and the grass-covered huts of Mali. It’s become a booming, regional trade that ensnares children as young as two years old who don’t know the name of their village or how to return home.

One of the largest clusters of Koranic schools lies in the poor, sand-enveloped neighborhoods on either side of the freeway leading into Dakar.

This is where Coli’s marabout squats in a half-finished house whose floor stirs with flies. Amadu Buwaro sleeps on a mattress covered in white linen. The 30 children in his care sleep in another room with dirty blankets on the floor. It smells rotten and wet, like a soaked rag.

Buwaro is a thin man in his 30s who wears a pressed olive robe and digital watch. The children wear T-shirts black with filth. He expects them to beg to pay the rent, because there are no fields here to till.

But their earnings far exceed his rent of US$50. If the boys meet their quotas, they bring in around US$650 a month in a nation where the average person earns US$150.

Buwaro expects the children to suffer to learn the Koran, just as he did at the hands of his teacher.

So when Coli failed to return, Buwaro was furious. He flipped open his flashy silver cellphone and called another marabout who kept a blue planner with names of runaway boys. The list stretched down the page. He added Coli’s name.

His tomato can tucked under one arm, Coli jumped on the back of a bus, holding on to the swinging rear door. He was hundreds of kilometers from the village where he grew up speaking Peuhl, a language not commonly heard in Dakar.

He could not ask the Senegalese for help. So he got directions in Peuhl from other child beggars, who like him were trafficked here from the zone of green savannah just outside Senegal.

Coli made his way to a neighborhood where he had heard of a place that gave free food to children like him. The shelter’s capacity is 30 children, but it usually houses at least 50.

“Do you know where you come from?” asked the kind-faced woman at Empire des Enfants.

Coli knew the name of his mother, but not how to reach her. He knew the name of the region where he was born, but not his village.

“My mother is black,” he said. “I’m sure I’ll recognize her.”

The shelter worker told Coli what to do if his marabout came. We will protect you, she said. If he tries to grab you, scream.

Days went by. Maybe weeks. Then Coli’s marabout arrived.

In 2005, Senegal made it a crime punishable by five years in prison to force a child to beg. But the same law makes an exception for children begging for religious reasons. Few dare to cross marabouts for fear of supernatural retaliation.

Coli’s marabout entered the shelter flanked by a column of religious leaders in cascading robes that tumbled onto the ground.

One of them stabbed his finger at the clouds and yelled out, “The sky will fall down on you if you don’t hand over our children.”

The shelter is used to such threats. But this time the group of marabout had discovered the center’s legal paperwork was not complete. They threatened to close the shelter if it did not hand over 11 boys.

To save more than 40 others, the shelter handed over the 11. Coli was on the list.

Back at the school, they beat the nine-year-old until he thought he was going to faint. At night, they dragged him off the floor, doused him in water and beat him again.

Three days later, he ran away again. When he arrived at the shelter, he said: “I want to go home to my mom.”

To find Coli’s mother, aid workers broadcast his name on the radio in Guinea-Bissau.

The names of over a dozen children also from Guinea-Bissau played in a continuous loop, like sonic homing pigeons trying to find their target.

No response. Some boys worried their parents might be dead.

“I’m sure my mother is still alive,” Coli reasoned. “When I left her she was well, so why wouldn’t she be well now?”

Underneath his bright eyes is another worry. Will she be angry that he disobeyed his teacher?

Over the past two years, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) has returned over 600 child beggars to their homes.

Several had been hit by cars. Some had scars on their backs. One 10-year-old was so hungry he ate out of the trash. Soon after he returned home, he vomited worms and died.

Almost all these boys had begged on behalf of Koranic instructors in Senegal.

“Cultural habits have been manipulated for the sake of exploitation,” said the IOM’s Laurent de Boeck, deputy regional representative for West and Central Africa.

Two months went by before a shelter worker pulled Coli aside. His parents were alive.

The 13 boys from Guinea-Bissau pile into a bus. Coli screams with glee as it takes off for the airport.

“Is this Guinea-Bissau?” one of them asks as they descend onto the cracked runway and enter the small airport of the nation’s capital.

“Senegal looks better,” says another.

Though Senegal is among the world’s poorest nations, it’s visibly more developed than Guinea-Bissau, listed 160th out of 177 countries on the UN’s human development index.

The capital they left had streets clogged with taxis and flashy 4-by-4s. The buildings were tall. The capital they returned to has squat, low buildings and crumbling colonial villas.

“I’m not sure I like it,” Coli confides.

As the bus leaves the capital, they pass villages of cone-shaped huts and fields where boys herd bulls. They sing songs, clapping their hands.

As they pull into the shelter where their parents were told to expect them, the boys fall silent.

Timidly, they file off the bus. A few of the 12 and 13-year-olds recognize their families. They approach them respectfully, shaking hands.

Coli’s mother is not there.

A judge tells the parents they will be jailed if they send their children away to beg again.

They have to sign a statement promising to protect their boys from traffickers. Most are illiterate, so they leave a thumbprint in blue ink next to their names.

“You sent your kids to hell,” the judge says. “You can’t say that because you are poor you’re going to allow your kids to be abused.”

His booming voice ricochets off the cracked walls of the building. The parents stare straight ahead.

But the conditions that made these families send their children to hell still persist.

Many of the villages do not have enough food. Few have schools.

In one, the schoolhouse is a bamboo enclosure that doubles as an animal corral.

“We haven’t had classes here in over a year,” an elderly man says as he ducks into the classroom and skirts a pile of bull manure.

The aid group pays for school fees and supplies. But the stipend cannot cover the economic worth of a child. Some of the children returned in previous months now work as bricklayers and goatherds.

Others have already been sent back to the marabout by their parents.

The idea of child trafficking as a crime is so new in the region that no African language has a word for it, experts say.

With each passing day, more parents and relatives come, but not Coli’s.

On the third day, the shelter pays for another radio address.

By the fourth, half the 13 children are gone.

The others become increasingly agitated. Maybe the radio is broken, Coli muses. His wet eyes fill with the invisible color of worry.

Early on the fifth morning, a woman in a pressed peach robe walks up to the shelter.

Coli rushes outside. He stands a few meters away as tears topple down his cheeks. She covers her face with her veil and weeps.

The two sit side-by-side in plastic chairs. Coli’s mother looks at her feet. Her family is poor, she says, and she wanted Coli to get an education. It took her several days to reach the shelter because she didn’t have US$2 for the bus fare.

For more than an hour, Coli cries. Tears run down either side of his cheeks, forming two watery garlands. They meet at his chin and plop down on his collar bone, pooling above his shirt.

She stands up and wipes his chin. They leave, crossing the dusty boulevard.

Her arm reaches around his shoulder and the long sleeve of her robe falls around the little boy. It hides him from the remaining children, who silently watch Coli go home.

Soon after Coli left, his marabout traveled to Guinea-Bissau. He angrily demanded to know why Coli had run away.

Ashamed, Coli’s father promised to make up for the boy’s bad behavior.

He is sending the marabout two more sons.

US President Donald Trump’s second administration has gotten off to a fast start with a blizzard of initiatives focused on domestic commitments made during his campaign. His tariff-based approach to re-ordering global trade in a manner more favorable to the United States appears to be in its infancy, but the significant scale and scope are undeniable. That said, while China looms largest on the list of national security challenges, to date we have heard little from the administration, bar the 10 percent tariffs directed at China, on specific priorities vis-a-vis China. The Congressional hearings for President Trump’s cabinet have, so far,

US political scientist Francis Fukuyama, during an interview with the UK’s Times Radio, reacted to US President Donald Trump’s overturning of decades of US foreign policy by saying that “the chance for serious instability is very great.” That is something of an understatement. Fukuyama said that Trump’s apparent moves to expand US territory and that he “seems to be actively siding with” authoritarian states is concerning, not just for Europe, but also for Taiwan. He said that “if I were China I would see this as a golden opportunity” to annex Taiwan, and that every European country needs to think

For years, the use of insecure smart home appliances and other Internet-connected devices has resulted in personal data leaks. Many smart devices require users’ location, contact details or access to cameras and microphones to set up, which expose people’s personal information, but are unnecessary to use the product. As a result, data breaches and security incidents continue to emerge worldwide through smartphone apps, smart speakers, TVs, air fryers and robot vacuums. Last week, another major data breach was added to the list: Mars Hydro, a Chinese company that makes Internet of Things (IoT) devices such as LED grow lights and the

US President Donald Trump is an extremely stable genius. Within his first month of presidency, he proposed to annex Canada and take military action to control the Panama Canal, renamed the Gulf of Mexico, called Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy a dictator and blamed him for the Russian invasion. He has managed to offend many leaders on the planet Earth at warp speed. Demanding that Europe step up its own defense, the Trump administration has threatened to pull US troops from the continent. Accusing Taiwan of stealing the US’ semiconductor business, it intends to impose heavy tariffs on integrated circuit chips