he US' self-confidence is on the wane.

It is not just that the economy seems to be in a recession, although that is no doubt a big part of it. Foreign policy reversals and worries that the US cannot compete in a changing world also play a role.

Similar fears have arisen before and have eventually been proved wrong. But that has always taken time, perhaps because such deep fears can be self-fulfilling as both businesses and consumers cut back spending -- something that appears to be happening now.

Evidence of the loss of confidence came last week when the Conference Board released its consumer confidence survey for last month. What stood out was how far economic expectations have fallen.

The amount of pessimism -- as shown by people who forecast things will get worse -- is not quite at record highs. But the amount of optimism that things will get better is as low as it has been in the four decades that the Conference Board has been asking questions.

Why is that? It is not just the decline in home prices and the increase in mortgage defaults. Nor is the seemingly interminable war in Iraq the major cause, although it, too, is probably playing a role.

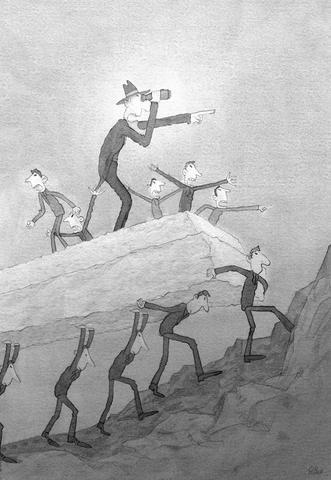

Instead, it is evidence that the US is no longer a leader, or perhaps even competent, in one area in which we believed it excelled.

That area is finance. Only months ago, US financial institutions were pre-eminent in the world economy. It was the country that invented all the new financial products and made lots of money from them. It was US investment banks that were called upon to advise companies and governments in other countries, and then to arrange the financing they needed.

Now that reputation lies in tatters. Our big banks have been forced to turn to places like China and Abu Dhabi for capital as losses have mounted. But no similar angel turned up for Bear Stearns, and the US Federal Reserve Board had to step in to avert disaster.

The Fed, which only months ago seemed omniscient, now seems to be making it up as it goes along.

Perhaps the most similar loss of confidence -- at least since the end of the Great Depression -- came in late 1973, when a sudden increase in the price of oil brought on a severe recession. The continuing war in Vietnam also hurt confidence, and then-US president Richard Nixon was under siege in the Watergate scandal, which led to his resignation the following year.

It was in December 1973 that the Conference Board's consumer expectations index hit the lowest level ever, 45.2. Last week's reading, 47.9, ranks second.

In some ways, there is even less optimism now than there was then. A lower proportion of those surveyed expect business conditions to improve within six months, and the percentage of people who think their own income will rise is much lower now than it was then.

Only in jobs is there more optimism now, and the difference is small.

The other time that is comparable in terms of a loss of confidence was early 1980, when the country was facing a new recession and imposing credit controls in what seemed to be a panicky -- and unsuccessful -- response to rising inflation. The Iranian hostage crisis seemed insoluble and then-US president Jimmy Carter was facing a primary challenge within his own party.

Expectations also declined in 1990, although not quite as far. That came after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait and amid worries about a seeming inability to compete with Japan, whose economic success was envied and resented. In fact, the Japanese bubble was bursting, but that was not clear then.

US Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson has tried to be reassuring. But squabbling in Washington over what should be done may have contributed to a sense of drift.

In a speech last month, Paulson dismissed as "not yet ready for the starting gate" some proposals by congressional Democrats.

He said he was trying to avoid "unnecessary capital market turmoil," which seemed to imply he had no problem with necessary turmoil, and he cautioned against efforts to "slow the housing correction" that he deemed healthy.

That statement may not have encouraged fearful homeowners.

"I am constantly asked how much longer will this take to play out and if this is the worst period of market stress I have experienced," he said in a speech to a Chamber of Commerce group.

"I respond that every period of prolonged turbulence seems to be the worst until it is resolved. And it always is resolved," he said.

"Our economy and our capital markets are flexible and resilient, and I have great confidence in them," he said.

That confidence is not shared by many in the public, however.

Nor is it only consumers who are scared. Corporate executives tell pollsters they are worried and are cutting back on capital spending. Many, according to a poll of chief financial officers by Duke University and CFO magazine, think the recession will not end until next year.

By then, there will be a new US president. And the political seers may want to note that the Conference Board's expectation index, which dates to 1967, has fallen below 60 in just 10 surveys before this year -- in 1973 to 1974, 1980 and 1990 to 1991.

In the presidential election after each of those crises of confidence, the incumbent party lost the White House.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its