Minoru Mori, Japan's most prolific developer, will finish the world's tallest building in May. Many of his colleagues might consider the 101-story Shanghai World Financial Center the crowning achievement of a long career, but Mori has lots of plans for a 73-year-old.

As president of Mori Building of Tokyo, he has remade the city's skyline with half a dozen high-rises, including a US$4 billion megacomplex, Roppongi Hills. Now, he is fielding offers to build skyscrapers like the Shanghai center in Bangkok and Singapore. And he is planning to build or help build 10 more huge complexes like Roppongi Hills in downtown Tokyo, including one that could be Japan's tallest, over the next 10 to 15 years.

He is also talking to Chinese and Middle East sovereign wealth funds about raising tens of billions of dollars to finance the projects.

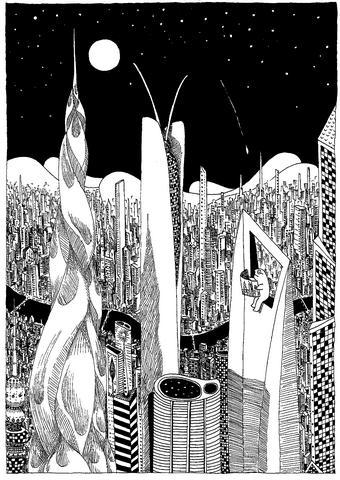

At a time when urban planners in the West frown on hulking high-rises as forbidding, Mori presents a new Asian urban sensibility, where architecture reflects soaring economic ambition, leading to mighty projects that dwarf the individual.

"Asia is different from the United States and Europe," Mori said in an interview in his Roppongi Hills office. "We dream of more vertical cities. In fact, the only choice here is to go up and use the sky."

Even in a region where builders churn out skyscrapers as on an assembly line, Mori's have stood out. His projects have won attention, and their share of controversy, for their great impact and scale, helping make him one of the few real estate investors in Asia known by name, like the Hong Kong billionaires Stanley Ho (何鴻燊) and Li Ka-shing (李嘉誠).

By focusing on a few long-term projects and shunning speculative buying and selling, his company escaped the real estate bubble of the 1980s and its collapse soon thereafter.

Mori's unlikely career began when he set aside an existentialist novel he was working on in 1959 to join his father's fledgling real estate business. Over the next half-century, the family-owned Mori Building grew from a single rice shop into a US$12 billion empire of 121 buildings, most around the southern Toranomon-Roppongi international business district of Tokyo.

"I shifted from writing literature to making buildings," said Mori, who played a leading role in the company even before formally taking over from his retired father, Taikichiro, in 1993.

"Both are creative efforts and attempts to enrich people somehow," he said.

Mori exudes the air of a university professor rather than a real estate mogul. But the Mori clan, which has included his two brothers, elbowed its way to the top of an insider-dominated business, competing with industrial groups and politically connected construction companies.

Real estate specialists say the Moris succeeded by reading the future better than their rivals and putting up buildings that fit the needs of a fast-developing Japanese economy.

The business attracted global tenants by constructing some of the city's first modern office buildings; the first 45 had numbers instead of names. In the 1980s, Mori steered the family toward building high-rise complexes, helping earthquake-prone Tokyo overcome its fear of skyscrapers.

Projects can move slowly in Japan. Roppongi Hills and Mori's first big high-rise complex, Ark Hills, which opened in 1986, each took 17 years to complete. Much of that time was spent cutting through red tape and persuading residents to move.

Even in the 1990s, when land prices were tumbling, he persuaded banks and investors to lend him billions of dollars for his projects. But his heavy borrowing loaded Mori Building with debt of around US$8 billion, almost six times its annual revenue.

Mori's willingness to use debt led to a parting of ways with his younger brother, Akira, who started his own real estate company, Mori Trust. The oldest brother, Kei, died in 1990.

Within his company, Mori is known for both long-term vision and a preoccupation with small details. At a recent meeting to plan a 46-story building -- one of his 10 new complexes -- he spent most of an hour discussing what type of landscaping would best attract fireflies and keep away crows. And he is about to begin construction of a skyscraper in Tokyo that, when completed in 2012, will have taken more than 28 years to finish.

His patience has paid off overseas. The Shanghai tower required 14 years, with long interruptions from the Asian financial crisis of 1997 to 1998 and the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington on Sept. 11, 2001.

The building in Tokyo, when completed late in May, will briefly hold the title of the world's tallest before a higher one is finished later in the year in Dubai.

With Mori's successes have come detractors. Japanese nationalists accuse him of cozying up to foreigners because he has so many international tenants. Preservationists assail his skyscrapers for destroying Tokyo's traditional low-rise feeling. Academics call him dated for wanting to erect monolithic high-rises at a time when smaller-scale, pedestrian-friendly developments are in vogue among urban planners.

"Mr Mori has been remarkable in his ability to bring a strong vision to a city that has otherwise lacked an overall vision," said Junichiro Okata, a professor of urban planning at the University of Tokyo.

"Whether Mr Mori has brought the correct vision or not is an entirely different matter," Okata said.

Controversy has also surrounded the best-known development, Roppongi Hills, with its 54-story barrel-like office tower.

When it was completed in 2003, the opulent complex -- which includes fashion boutiques, condominiums and a television studio -- was heralded as a symbol of the end of the country's "lost decade."

But it soon turned into a symbol of the excesses of the Japanese revival, when its most famous tenant, a Ferrari-driving Internet entrepreneur, Takafumi Horie, was arrested for insider trading.

Mori says his aim is to replace Tokyo's chaotic, low-rise industrial-era neighborhoods with a more modern and convenient urban environment.

Not everyone approves of his designs.

"Mr Mori knows these kind of projects better than anyone," said Yuichi Fukukawa, a professor of urban planning at Chiba University.

"It's scary, but if he wants to fill Tokyo with more Roppongi Hills, he can do it," Yuichi said.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its