The question that has dominated Russian politics, and world discussion of Russian politics -- "Will he [Russian President Vladimir Putin] or won't he stay in power?" -- has now been settled. He will and he won't.

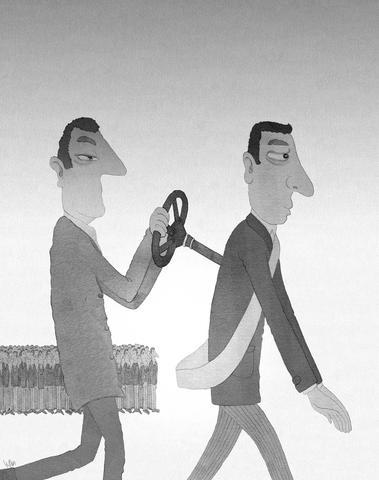

The election of Putin's longtime acolyte and handpicked successor, Dmitri Medvedev, as Russia's president means that Putin is formally surrendering all the pomp and circumstance of Kremlin power. But now it looks like 21-gun salutes and first place in protocol lines are the only things that Putin is giving up -- if that. In opting to become Medvedev's prime minister, Putin sees himself as coming closer to the machine of power, because he will obtain minute-by-minute control of the government.

This bizarre transfer of office but not power -- perhaps a slight improvement on state governors in the US south who used to hand their offices to their wives when their term-limits expired -- is Putin's scenario. But what if it is not Medvedev's? What if Medvedev, after a few years, becomes as independent of his patron as Putin became of former Russian president Boris Yeltsin, the man who put him on the Kremlin throne? Should that turn out to be the case, it will be useful to know what, if anything, Medvedev stands for.

One thing immediately stands out about Medvedev: he has only indirect ties to the siloviki, the ex-KGB and military men who have dominated the Putin era. As a trained lawyer, he should in principle understand the importance of the rule of law. And, as deputy prime minister since 2005, he oversaw the Russian National Priority Projects (a set of policies to develop social welfare), which has given him a clearer insight into Russia's deep flaws than any of the silovik, with their focus on getting and maintaining personal power, could ever have.

Medvedev's promises to modernize the feudal conditions of Russia's army also set him apart, given the absolute failure of military reform during the Putin era. Moreover, he appears to believe that confrontations between the state and civil society are counterproductive. Indeed, he insists that the government's job is to strengthen civil society based on the rule of law.

All of this sounds good. The problem is that we have heard it all before from Putin -- another trained lawyer -- at the start of his presidency, when he promised a "dictatorship of law," military reform, land reform, and, consequently, a return of Russia's agriculture dream, ruined by the post-1917 planned economy. Instead, he and his ex-KGB comrades-in-arms placed themselves above the law, abandoned meaningful social and economic reform, and coasted on high world oil prices.

There is hope, however slight, that, unlike Putin, Medvedev may mean what he says. His non-KGB, non-military background suggests that his conception of the rule of law may not be entirely shaped by a cynical love of power.

But Medvedev's track record is not encouraging. As Russia's deputy prime minister since 2005, he has not gone beyond consoling rhetoric. For eight years, he carried out silovik orders, combining the role of Kremlin gray cardinal with treasurer of the main source of silovik power, the chairmanship of state-owned energy giant Gazprom. Medvedev also coordinated Russia's interference in the 2004 Ukrainian election, which led to that country's "Orange Revolution."

More broadly, as the head of Putin's presidential administration, Medvedev directly oversaw the construction of today's authoritarian system of Russian governance. So it was only appropriate that he should become deputy prime minister for social affairs in 2005, because he had already succeeded in largely bringing these affairs to a halt.

Russia is supposed to be a mystery, but it rarely surprises the world in living down to expectations: most analysts were certain that Putin would find a way to stay in power even without amending the Constitution. And so he did.

Indeed, Russia's liberal promises have been shattered time after time. Communist Party general secretary Nikita Khrushchev's de-Stalinization reforms ended with his successor Leonid Brezhnev's stagnation; Yeltsin's democratization resulted in Putin's authoritarianism. In the sadly immortal words of Victor Chernomyrdin, prime minister during the Yeltsin era, "We wanted for the better, but it turned out to be like always."

But, as predictable as Russia's undemocratic system of governance usually is, the country does defy expectations once in a while. Khrushchev denounced his mentor, Stalin. Former Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev was originally installed in power to press on with his predecessor Yuri Andropov's KGB-inspired vision of communism, but instead diverted the Soviet Union's course into glasnost and perestroika, and accidentally into freedom.

What if Putin is wrong in his choice of successor, and Medvedev refuses to be his clone, but instead follows in the footsteps of Khrushchev, Gorbachev and Yeltsin? What if the supposed puppet starts to pull the strings?

Nina Khrushcheva teaches international affairs at The New School and is senior fellow at the World Policy Institute in New York.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

US president-elect Donald Trump continues to make nominations for his Cabinet and US agencies, with most of his picks being staunchly against Beijing. For US ambassador to China, Trump has tapped former US senator David Perdue. This appointment makes it crystal clear that Trump has no intention of letting China continue to steal from the US while infiltrating it in a surreptitious quasi-war, harming world peace and stability. Originally earning a name for himself in the business world, Perdue made his start with Chinese supply chains as a manager for several US firms. He later served as the CEO of Reebok and

Chinese Ministry of National Defense spokesman Wu Qian (吳謙) announced at a news conference that General Miao Hua (苗華) — director of the Political Work Department of the Central Military Commission — has been suspended from his duties pending an investigation of serious disciplinary breaches. Miao’s role within the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) affects not only its loyalty to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), but also ideological control. This reflects the PLA’s complex internal power struggles, as well as its long-existing structural problems. Since its establishment, the PLA has emphasized that “the party commands the gun,” and that the military is

Since the end of former president Ma Ying-jeou’s (馬英九) administration, the Ma Ying-jeou Foundation has taken Taiwanese students to visit China and invited Chinese students to Taiwan. Ma calls those activities “cross-strait exchanges,” yet the trips completely avoid topics prohibited by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), such as democracy, freedom and human rights — all of which are universal values. During the foundation’s most recent Chinese student tour group, a Fudan University student used terms such as “China, Taipei” and “the motherland” when discussing Taiwan’s recent baseball victory. The group’s visit to Zhongshan Girls’ High School also received prominent coverage in

India and China have taken a significant step toward disengagement of their military troops after reaching an agreement on the long-standing disputes in the Galwan Valley. For government officials and policy experts, this move is welcome, signaling the potential resolution of the enduring border issues between the two countries. However, it is crucial to consider the potential impact of this disengagement on India’s relationship with Taiwan. Over the past few years, there have been important developments in India-Taiwan relations, including exchanges between heads of state soon after Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s third electoral victory. This raises the pressing question: