The first time Jose Freeman heard his tribe's lost language through the crackle of a 70-year-old recording, he cried.

"My ancestors were speaking to me," Freeman said of the sounds captured when American Indians still inhabited California's Salinas Valley. "It was like coming home."

The last native speaker of Salinan died almost 50 years ago, but today many indigenous people are finding their extinct or endangered tongues, one word or song at a time, thanks to a linguist who died in 1961 and academics at the University of California, Davis, who are working to transcribe his life's obsession.

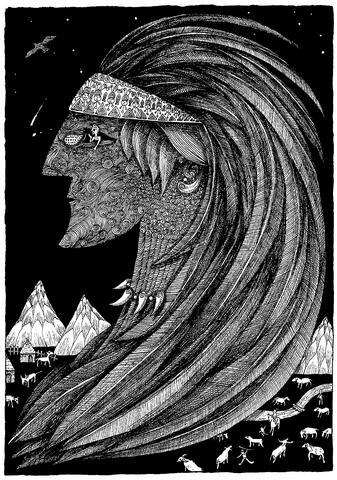

ILLUSTRATION: MOUNTAIN PEOPLE

Linguist John Peabody Harrington spent four decades gathering more than 1 million pages of phonetic notations on languages spoken by tribes from Alaska to South America. When the technology became available, he supplemented his written records with audio recordings -- first using wax cylinders, then aluminum discs. In many cases his notes provide the only record of long-gone languages.

Martha Macri, who teaches California Indian Studies at UC Davis and is one of the principal researchers on the J.P. Harrington Database Project, is working with American Indian volunteers to transcribe Harrington's notations. Researchers hope the words will bridge the decades of silence separating the people Harrington interviewed from their descendants.

Freeman hopes his four-month-old great-granddaughter will grow up with the sense of heritage that comes with speaking her ancestors' language.

"When we lose our language, we're getting cut off from our roots," he said. "The world view that our ancestors carried is quite different from the Euro-American world view. And their language can carry that world view back to us."

Although it will be years before all the material can be made available, some American Indians connected to the Harrington Project have already begun putting it to use. Members of Freeman's tribe gather on their ancestral land every month to practice what they have learned -- a few words, some grammar, old songs.

"The ultimate outcome is to get it back to the communities it came from," Macri said.

By all accounts, Harrington was a devoted, if somewhat eccentric, scholar. Sometimes he spent 20 or 30 minutes on one word, saying it over and over until the person he was interviewing agreed he had gotten the pronunciation correct, said Jack Marr, who met Harrington as a 12-year-old and worked as his assistant into his 20s.

"They trusted him," Marr said of the Indians they worked with.

"A lot of people, if they tried to walk in and say `I want to record you,' they'd get thrown out. But not Harrington. I think people recognized that we were doing this for posterity."

Harrington's sense of urgency animates the letters he sent to Marr nearly every day.

"Rain or no rain, rush," Harrington said in one letter. "Dying languages depend on you."

However, that same drive has confounded efforts to pass the words down to new generations.

For instance, Harrington was so focused on gathering information that he spent little time polishing his work for publication, according to Marr. He hated wasting precious time being cooped up in an office.

And he was so deeply mistrustful of other researchers that he stashed much of his research as he traveled, deliberately keeping it out of reach of his colleagues. He kept even his employers at the Bureau of American Ethnology -- now the National Anthropological Archives -- in the dark about where he was and what he was doing, routing his mail through Marr's mother to cover his tracks.

After his death, the federal archives received boxes of Harrington's notes, recordings and other material from people who found them in barns and basements across the West. It took the archives until 1991 to transfer the voluminous notes to microfilm.

While linguists, archeologists, botanists and others have spent the years since combing through the files, Macri says the trove of information has remained all but inaccessible to members of the tribes themselves.

The Harrington Project was created with the goal of returning the words to the people who can imbue them with life again, as well as making the material more accessible to academics.

The researchers are teaching tribal members across California how to read Harrington's cramped handwriting and decipher his notation system.

Macri's team focuses on the more than 100 California languages Harrington catalogued, such as Wiyot, Serrano and Luiseno, for which there are few other records.

"It would be hard to exaggerate the linguistic diversity that existed at one time in California," Macri said. "It was more common to be multilingual than not."

Jacob Gutierrez, a member of the San Gabriel Band of Mission Indians -- Pipiimaram, in the tribe's own language -- has decoded all the material Harrington gathered on his people -- over 6,000 pages, and is now working on information about their linguistic neighbors.

"I find it to be the most rewarding work I have ever done," he said. "Every new word, story or song is an absolute treasure for me and my people."

Karen Santana, who started working on Harrington's notes about her Central Pomo tribe while she was a student at UC Davis, is drawing plans for a dictionary with phonetic spellings.

"I want to develop a system that will make sense to others," Santana said. "It's a lifelong goal, publishing something ... that my tribe can refer to."

Marr said Harrington would have been satisfied to see languages born again from his notes and recordings.

"But he would have felt very sad he didn't get more. He always wanted to do more," Marr said.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its