The last things Mohammed Salim remembered were the knees pinning him to the ground, the guns pointed at his head, and, finally, the injection that sent him into oblivion.

When he awoke, he was in agonizing pain, uncertain where he was or why he was wearing a hospital gown.

"We have taken your kidney," a masked man calmly explained. "If you tell anyone, we'll shoot you."

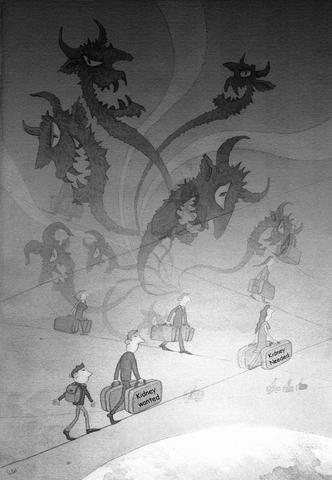

Salim was one of the last victims in an organ transplant racket that police believe sold up to 500 kidneys to clients who traveled to India from around the world over the past nine years.

Police say that when they raided the operation's main clinic in this upscale New Delhi suburb late last month, they broke up a ring spanning five Indian states and involving at least four doctors, several hospitals, two dozen nurses and paramedics and a car outfitted as a laboratory.

Subsequent raids uncovered a kidney transplant waiting list with 48 names and, in one clinic, five foreigners -- three Greeks and two Americans of Indian descent -- who authorities believe were waiting for transplants.

Only one doctor has been arrested so far and police are searching for the alleged ringleader, Amit Kumar, who has several aliases and has been accused in past organ transplant schemes elsewhere in India. Authorities believe he's fled the country.

"Due to its scale, we believe more members of the Delhi medical fraternity must have been aware of what was going on," Gurgaon Police Commissioner Mohinder Lal told reporters last week.

There long have been reports of poor Indians illegally selling kidneys, but the transplant racket in Gurgaon is one of the most extensive to come to light -- and the first with an element of so-called medical tourism.

The low cost of medical care in India has made it a popular destination for foreigners in need of everything from tummy tucks to heart surgery.

The Gurgaon kidney transplant racket, however, was not the types of operation the medical community wanted in the headlines. The case has shocked the country, sparking debate about medical ethics and organ transplant laws.

Some "donors" were forced onto the operating table at gunpoint, while others were tricked with promises of work, Lal said. There were also some who sold kidneys willingly, usually for between US$1,125 and US$2,250, the Hindustan Times newspaper reported. The sale of human organs is illegal in India.

Salim, 33, a laborer with five children, said he was lured from his home town a few hours outside New Delhi by a bearded stranger offering a construction job that paid 150 rupees (US$3.75) a day, as well as food and lodging. He was told the work would last three months.

"I thought I could earn money and save it for my children," he said from a government hospital in Gurgaon, where he is recovering under police protection.

He was first taken to a two-room house "in the jungle" outside New Delhi where two gunmen held him for six days, he said. Then he was taken to a bungalow in Gurgaon, where armed men took a blood sample at gunpoint.

Salim said he tried to escape, but the doors were locked and within moments, the men were on top of him, sticking him with another needle while he slowly lost consciousness.

When he awoke and learned what happened, Salim thought he was soon to die -- he didn't know you could live with one kidney. He lay in a haze of pain and confusion for about a day, when the men, apparently tipped off to the coming raid, told him they had to move him.

Minutes later, police burst into the house and rescued Salim and two other men who also had their kidneys taken. He never received any money, he said.

"I don't know how I will survive," said Salim, whose five children were at the hospital. "I am the only earner in the family and the doctors said I can't do heavy work."

Shakeel Ahmed, 28, was in the hospital bed next to Salim, wincing in pain as he told his story. He is unmarried and has no children, but he is responsible for five nieces and nephews, he said.

"I'm sad, I'm angry. I don't know how I will care for them," Ahmed said, pointing to his elderly parents sitting on the foot of his bed. "Why me?"

US President Donald Trump created some consternation in Taiwan last week when he told a news conference that a successful trade deal with China would help with “unification.” Although the People’s Republic of China has never ruled Taiwan, Trump’s language struck a raw nerve in Taiwan given his open siding with Russian President Vladimir Putin’s aggression seeking to “reunify” Ukraine and Russia. On earlier occasions, Trump has criticized Taiwan for “stealing” the US’ chip industry and for relying too much on the US for defense, ominously presaging a weakening of US support for Taiwan. However, further examination of Trump’s remarks in

As the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and its People’s Liberation Army (PLA) reach the point of confidence that they can start and win a war to destroy the democratic culture on Taiwan, any future decision to do so may likely be directly affected by the CCP’s ability to promote wars on the Korean Peninsula, in Europe, or, as most recently, on the Indian subcontinent. It stands to reason that the Trump Administration’s success early on May 10 to convince India and Pakistan to deescalate their four-day conventional military conflict, assessed to be close to a nuclear weapons exchange, also served to

China on May 23, 1951, imposed the so-called “17-Point Agreement” to formally annex Tibet. In March, China in its 18th White Paper misleadingly said it laid “firm foundations for the region’s human rights cause.” The agreement is invalid in international law, because it was signed under threat. Ngapo Ngawang Jigme, head of the Tibetan delegation sent to China for peace negotiations, was not authorized to sign the agreement on behalf of the Tibetan government and the delegation was made to sign it under duress. After seven decades, Tibet remains intact and there is global outpouring of sympathy for Tibetans. This realization

After India’s punitive precision strikes targeting what New Delhi called nine terrorist sites inside Pakistan, reactions poured in from governments around the world. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) issued a statement on May 10, opposing terrorism and expressing concern about the growing tensions between India and Pakistan. The statement noticeably expressed support for the Indian government’s right to maintain its national security and act against terrorists. The ministry said that it “works closely with democratic partners worldwide in staunch opposition to international terrorism” and expressed “firm support for all legitimate and necessary actions taken by the government of India