Within the first few minutes of Barack Obama's famous address to the Democratic convention in Boston, he mentioned one word five times. "My grandfather had larger dreams"; "they, too, had big dreams"; "a common dream"; "my parents' dreams live on"; "that is the true genius of America -- a faith in simple dreams."

That speech, on July 27, 2004, lasted 15 minutes and put Obama on the map. The Chicago Herald said he "hit every note," the right-wing commentator Robert Novak called him one of the Democrats' hottest properties and the Augusta Chronicle dubbed him the party's "promising new cub."

Promising new cub. What an enormous difference three-and-a-half years can make. Obama is no longer a mere cub. With a gale now blowing in his sails after Iowa and New Hampshire, he has a real chance to become the Democratic candidate for November's presidential elections.

His potential has emerged with lightning speed; he is the political equivalent of Facebook, another phenomenon launched in 2004 that feels as though it has been around for ever.

Dreaming has played a crucial part. At crucial moments through his career he had what he calls the "audacity of hope": where others might have stepped back, he reached out, both in terms of his personal ambition and in terms of his appeal to supporters outside the natural Democratic tent.

When he made the Boston speech he was not even yet in Congress: He was a Chicago lawyer running at the time for one of two Illinois seats in the US Senate. That race was in itself a long shot: a black man, as he says in his first book Dreams from My Father, "without organizational backing or personal wealth, and with a funny name," competing to become only the third African American since the post-civil war period of Reconstruction to serve in the Senate. He won, galvanizing support in white areas as well as black.

Look further back still and the pattern is repeated. In 1990, while a second-year student at Harvard, he had the audacity to stand for election to head the Harvard Law Review, one of the country's most prestigious legal publications. He beat off 18 other candidates to become its president (savor the moment: He was elected president Obama).

REACHING OUT

David Goldberg, a civil rights lawyer who was a runner-up in that poll, recalls that Obama won by reaching out to right-wing law students, several of whom went on to become key legal advisers in the Bush administration: "We were a really polarized group of students, and he managed to span us all."

Further back still you see the dreams of his white mother from Kansas who had no money yet managed to send Barack, aged four, to an international school while they were in Indonesia. Every morning she would wake him up at 4am to give him English lessons before school.

Or go back to the very beginning and his parents' decision to pass on to him the name of his father, a black Kenyan who had come to the US to study but separated from his mother to return to Kenya when the boy was two. They gave him the name Barack ("blessed") -- an audacious act in itself in 1961, because when they married, Obama says, "miscegenation still described a felony in over half the states in the union."

Obama is, at least at this moment, truly blessed. But there is a long way to go before the inauguration ceremony at the White House on Jan. 20 next year.

Before he takes his place as first black president of the US, he has to convince not just his own party but a nation to follow him. To adopt a phrase that he himself used on victory night in Iowa last week: Is America ready to believe again?

If Obama's bid for the White House could be boiled down to cold numbers, the odds are not great. The senator from Illinois is among a tiny minority of the country's 38 million or so African Americans who have attained high elected office. He is the only serving black senator in Congress -- at 1 percent of the total, grossly beneath the 12 percent of Americans who are black. At governor level there have only been two black Americans elected since Reconstruction -- Douglas Wilder of Virginia in 1990 and Deval Patrick of Massachusetts last year.

Some black leaders look at these stark facts, ponder the relatively rare presence of African Americans at the top of the political pyramid and are sceptical about Obama's chances.

Take Robert Ford, a black state senator from South Carolina, which holds a crucial Democratic primary on Jan. 26. He is supporting Senator Hillary Clinton because he does not believe Obama can beat the Republicans. He points out that of about 8,000 black elected officials in the US, 99 percent represent districts with a 50 percent or more black population. In other words, black politicians do not get elected outside black areas.

He experienced the trend himself. When he ran for a majority white area, despite years of public service, he lost.

"I would love in my lifetime to see a black president, but is it possible this November? I don't see how," he said.

Nor do the precedents set by other black candidates running for president offer much succor. None has so far been nominated, and of those who have run in the primaries Jesse Jackson is the only candidate to have taken any states. The first to run was the comedian Dick Gregory in 1968; he garnered 47,000 votes (among them that of the writer Hunter S. Thompson). Shirley Chisholm was the first to run for nomination by one of the two main parties in 1972, and Al Sharpton also ran in 2004.

Jackson's two attempts in 1984 and 1988 were equally unsuccessful, although at this point in the reckoning the indicators start to swing toward the positive. Though he never came close to taking the Democratic nomination, Jackson did carry five states in 1984 and 11 states four years later.

WHITE AND BLACK

More importantly, he also began to enthuse white as well as black people and energized 2 million largely young new voters to go to the polls -- a strength that Obama, aided by the new tools of MySpace and Facebook, has been replicating.

Other evidence suggests that history is moving in Obama's direction. When Gallup most recently, in 2003, asked voters if they were willing to elect a black president, 92 percent said yes. Opinion polls on race are notoriously unreliable, but this statistic still contrasts strikingly with the answer given to the same question in 1958: 53 percent.

On top of that must be added the style and character of Obama's appeal. As Professor Merle Black of Emory University in Atlanta points out: "He is running as a candidate who happens to be black, not as a black candidate."

Obama is open about that strategy. In his second book, The Audacity of Hope, he says: "Rightly or wrongly, white guilt has largely exhausted itself in America; even the most fair-minded of whites tend to push back against suggestions of racial victimization."

Though he makes no attempt to hide his race, or to sweep racial issues out of sight, he does talk in general terms rather than specifics: The fight for justice has replaced the fight for racial justice, and the language of aspirations has replaced the vocabulary of anger. As Bernard-Henri Levy put it, Obama has decided "to stop playing on guilt and play on seduction instead."

Paul Sniderman, a political scientist at Stanford University, has run experiments based on random opinion polling that reveal a huge potential pool of support for politicians who talk about social justice in non-racial language.

"Our research showed that any politician that appeals on issues such as inequality, but does so in moral rather than racial terms, can draw on a big constituency. Obama is tapping into it, and showing how deep it goes," he said.

Which brings us back to the beginning and his 2004 speech. Obama is tapping into this well of support, with the explosive results we are seeing now, through the message of dreams and of hope. The paradox is that for a politician who claims to be everything new, he is wielding the oldest weapon in the American politician's armory: optimism.

OPTIMISM

"There is a stream of optimism that runs through American politics and persists," said Timothy McCarthy, a historian of race and social movements at Harvard University. "The founding fathers were dreamers: Jefferson took Locke's `life, liberty and property' and turned it into `life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.'"

More recently, two of the towering presidents of the 20th century, Franklin Roosevelt and Ronald Reagan, both drank heavily from the cup of optimism. Roosevelt used it to kick-start the country out of depression; Reagan, a student of Roosevelt's politics, embodied it in his famous catchphrase "Morning in America."

It's odd to think of Obama as the heir to Ronald Reagan, but in this regard there is something to that. And beyond Reagan, there was that other great exponent of hope and dreams: Bill Clinton.

Which is the ultimate paradox. Obama is running against the Clinton machine that should, by rights, have put its seal on the copyright of dreams so that no one else could grab it.

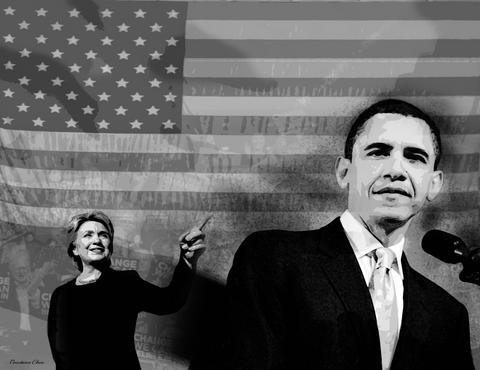

Yet, to the puzzlement of pundits, Hillary Clinton has been running a campaign that is all about the "I" of her past achievements and experience. Obama, by contrast, is all about the "we" of what the American people can achieve through faith in simple dreams.

US President Donald Trump is systematically dismantling the network of multilateral institutions, organizations and agreements that have helped prevent a third world war for more than 70 years. Yet many governments are twisting themselves into knots trying to downplay his actions, insisting that things are not as they seem and that even if they are, confronting the menace in the White House simply is not an option. Disagreement must be carefully disguised to avoid provoking his wrath. For the British political establishment, the convenient excuse is the need to preserve the UK’s “special relationship” with the US. Following their White House

Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention. If it makes headlines, it is because China wants to invade. Yet, those who find their way here by some twist of fate often fall in love. If you ask them why, some cite numbers showing it is one of the freest and safest countries in the world. Others talk about something harder to name: The quiet order of queues, the shared umbrellas for anyone caught in the rain, the way people stand so elderly riders can sit, the

After the coup in Burma in 2021, the country’s decades-long armed conflict escalated into a full-scale war. On one side was the Burmese army; large, well-equipped, and funded by China, supported with weapons, including airplanes and helicopters from China and Russia. On the other side were the pro-democracy forces, composed of countless small ethnic resistance armies. The military junta cut off electricity, phone and cell service, and the Internet in most of the country, leaving resistance forces isolated from the outside world and making it difficult for the various armies to coordinate with one another. Despite being severely outnumbered and

After the confrontation between US President Donald Trump and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy on Friday last week, John Bolton, Trump’s former national security adviser, discussed this shocking event in an interview. Describing it as a disaster “not only for Ukraine, but also for the US,” Bolton added: “If I were in Taiwan, I would be very worried right now.” Indeed, Taiwanese have been observing — and discussing — this jarring clash as a foreboding signal. Pro-China commentators largely view it as further evidence that the US is an unreliable ally and that Taiwan would be better off integrating more deeply into