The pineapples that grow on the steep hills above the Mekong River are especially sweet, the red and orange chilies unusually spicy, and the spring onions and watercress retain the freshness of the mountain dew.

For years, getting this prized produce to market meant that someone had to carry a giant basket on a back-breaking, daylong trek down narrow mountain trails cutting through the jungle.

That is changing, thanks in large part to China.

Villagers ride their cheap Chinese motorcycles, which sell for as little as US$440, down a dirt road to the markets of Luang Prabang, a charming city of Buddhist temples along the Mekong that draws flocks of foreign tourists. The trip takes one-and-a-half hours.

"No one had a motorcycle before," said Khamphao Janphasid, 43, a teacher in the local school whose extended family now has three of them. "The only motorcycles that used to be available were Japanese, and poor people couldn't afford them."

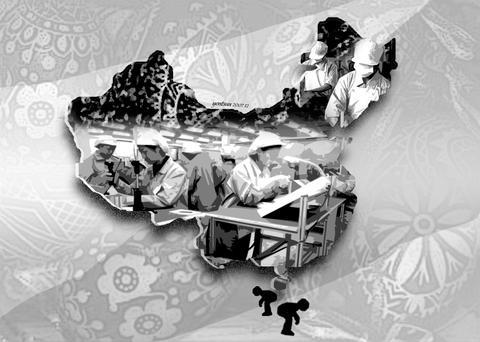

Inexpensive Chinese products are flooding China's southern neighbors like Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam. The products are transforming the lives of some of the poorest people in Asia, whose worldly possessions a few years ago typically consisted of not much more than one or two sets of clothes, cooking utensils and a thatch-roofed house built by hand.

The concerns in the West about the safety of Chinese toys and pet food are largely moot for the people in the remote villages here. As an introduction to global capitalism, Chinese products are met with deep appreciation.

"Life is better," Khamphao said, "because prices are cheaper."

Chinese television sets and satellite dishes connect villagers to the world. Stereos fill their houses with music. And the Chinese motorcycles often serve as transportation for families.

The motorcycles, typically with small but adequate 110cc engines, literally save lives, said Saidoa Wu, the village leader of Long Lao Mai, in a valley at the end of the dirt road adjacent to Long Lao Gao.

"Now, when we have a sick person, we can get to the hospital in time," said Wu, 43.

The improvised bamboo stretchers that villagers here used as recently as a decade ago to carry the gravely ill on foot are history. In a village of 150 families, Wu counts 44 Chinese motorcycles. There were none five years ago.

Chinese motorbikes fill the streets of Hanoi, Vientiane, Mandalay and other large cities in upland Southeast Asia. Thirty-nine percent of the 2 million motorcycles sold annually in Vietnam are Chinese brands, according to Honda, which has a 34 percent market share.Chinese exports to Myanmar, Laos and Vietnam amounted to US$8.3 billion in the first eight months of the year, up about 50 percent from the same period last year.

About seven years ago, residents here say, Chinese salesmen began arriving with suitcases filled with smuggled watches, tools and small radios; they would close up and move on when the police arrived.

More recently, Chinese merchants who speak only passable Lao received permission to open permanent stalls in the towns and small cities across the region. In Laos, these are called talad jin, or Chinese markets.

Khamphao and his neighbors all have US$100 Chinese-made television sets connected to Chinese-made satellite dishes and decoders, causing both joy and occasional tension among family members sitting on the bare concrete or dirt floors of their living rooms.

"I like watching the news," Khamphao said. "My children love to watch movies."

A two-hour interview with Khamphao was interrupted twice; once when his buffalo in the adjoining field gave birth to a healthy calf, and a second time when a cable TV channel was showing a scene from Lost in Translation in which Bill Murray's character sings an off-key rendition of Roxy Music's More Than This.

Khamphao's children, whose daily lives are largely confined to the mountain village, have picked up the Thai language from television, and they sing along to commercials broadcast from Thailand.

The enthusiasm for Chinese goods here is tempered by a commonly heard complaint: maintenance problems.

"The quality of the Japanese brands is much better," said Gu Silibapaan, a 31-year-old motorcycle mechanic in Luang Prabang.

People with money, he said, buy Honda, Yamaha and Suzuki motorcycles. People with lots of money buy cars.

Gu said he could distinguish a Japanese brand made in Thailand just by listening to the engine.

"It sounds more firm, and the engine noise is softer," Gu said.

Some Thai-made Japanese motorcycles can go 10 years without an engine overhaul. Chinese bikes, he said, usually need major repairs within three to four years.

"I want a motorcycle from Thailand, but I don't have the money," said Kon Panlachit, a police officer who brought his Jinlong 110cc motorcycle to Gu's shop for repairs recently.

"When I ride it, it makes a noise -- dap, dap dap," Kon said. "It's the second time I've brought it here for this problem."

The cheapest Thai-made Honda goes for 55,000 baht (US$1,670) -- four times the price of the cheapest Chinese bikes, which are sold under many brands.

The influx of Chinese motorcycles is keeping mechanics busy in Luang Prabang. A decade ago there were two or three repair shops in the city, Gu said. Now he counts 20.

Gu does not worry about maintenance for his own motorcycle.

"I have a Honda," he said.

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) caucus whip Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) has caused havoc with his attempts to overturn the democratic and constitutional order in the legislature. If we look at this devolution from the context of a transition to democracy from authoritarianism in a culturally Chinese sense — that of zhonghua (中華) — then we are playing witness to a servile spirit from a millennia-old form of totalitarianism that is intent on damaging the nation’s hard-won democracy. This servile spirit is ingrained in Chinese culture. About a century ago, Chinese satirist and author Lu Xun (魯迅) saw through the servile nature of

Monday was the 37th anniversary of former president Chiang Ching-kuo’s (蔣經國) death. Chiang — a son of former president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石), who had implemented party-state rule and martial law in Taiwan — has a complicated legacy. Whether one looks at his time in power in a positive or negative light depends very much on who they are, and what their relationship with the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) is. Although toward the end of his life Chiang Ching-kuo lifted martial law and steered Taiwan onto the path of democratization, these changes were forced upon him by internal and external pressures,

In their New York Times bestseller How Democracies Die, Harvard political scientists Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt said that democracies today “may die at the hands not of generals but of elected leaders. Many government efforts to subvert democracy are ‘legal,’ in the sense that they are approved by the legislature or accepted by the courts. They may even be portrayed as efforts to improve democracy — making the judiciary more efficient, combating corruption, or cleaning up the electoral process.” Moreover, the two authors observe that those who denounce such legal threats to democracy are often “dismissed as exaggerating or

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) caucus in the Legislative Yuan has made an internal decision to freeze NT$1.8 billion (US$54.7 million) of the indigenous submarine project’s NT$2 billion budget. This means that up to 90 percent of the budget cannot be utilized. It would only be accessible if the legislature agrees to lift the freeze sometime in the future. However, for Taiwan to construct its own submarines, it must rely on foreign support for several key pieces of equipment and technology. These foreign supporters would also be forced to endure significant pressure, infiltration and influence from Beijing. In other words,