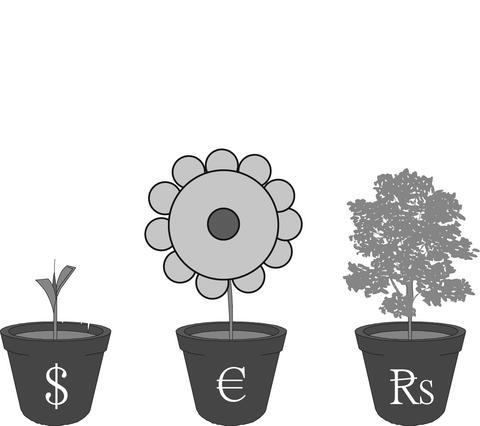

The Taj Mahal, one of the world's architectural masterpieces, welcomes about 2.5 million visitors each year -- provided they don't try to buy tickets with US dollars. India's most popular shrine announced last month that it would stop accepting the US currency and take only rupees, hurling yet another insult at the once mighty greenback.

The dollar, which has been snubbed by everybody from government officials in Kuwait and South Korea to top-earning Brazilian supermodel Gisele Bundchen, may not recover its luster. Economists say the currency, which has declined in five of the past six years against the euro, is caught in a downdraft as investors pour into Asia, prompting a tectonic shift in economic power from the US.

"Can it be turned around? Probably not totally," says Riordan Roett, a professor of political science at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. "The century of Asia has arrived, and the US and its European allies will need to adjust to that."

In Asia, an investment boom has boosted local currencies. China's roaring economy has grown an average of 10.4 percent in the past four years, fueled by record exports and a flood of foreign funds. That's pushed up the yuan since the government ended the currency's peg to the dollar in July 2005. As of Wednesday, the yuan -- managed against a basket of currencies -- climbed 12 percent against the dollar.

The Indian economy has grown at its fastest pace in the past four years since independence in 1947. That's helped to lift the rupee 12 percent against the US currency this year through Wednesday.

Dollar bulls say the currency, which rose to its highest in seven weeks against the euro on Wednesday, could rally further next year. They cite this year's fiscal US budget deficit, which fell to US$162.8 billion compared with US$412.8 billion three years earlier. And the current account deficit narrowed to US$178.5 billion in the third quarter after reaching a record US$217.3 billion in the period last year.

Deutsche Bank AG, the world's largest currency trader, predicts the dollar next year will rise about 2 percent more versus the euro, a currency shared by 15 nations as of next month.

Longer-term, the slowing US economy -- hurt by a banking and consumer credit meltdown that's only getting worse -- will weigh heavily on the dollar. Since August, the Federal Reserve has cut interest rates three times to 4.25 percent this month and traders in federal funds futures see about an even chance the rate will be 3.75 percent by May.

The Fed's moves, coupled with the European Central Bank's threat this month to raise rates, have tilted the odds against the US currency. This year, it fell 8 percent against the euro and 2 percent versus the British pound through Wednesday.

Asian and Persian Gulf nations are concerned that the flight from the dollar is feeding on itself and may spur a crisis of confidence.

Kuwait abandoned a dollar peg in May due to its weak buying power. South Korea's central bank last month urged shipbuilders to issue invoices in won, the country's currency, and take out more hedging policies to guard against the weakened dollar.

Peter Kenen, a professor of international finance at Princeton University, raises the possibility that the dollar's role as the world's dominant reserve currency may be coming to an end. The dollar's share of central banks' currency portfolios slid to 64.8 percent in this year's second quarter from 71 percent in 1999, the year the euro debuted, the IMF says.

Cash-rich governments, mostly in Asia and the Middle East, may shift as much as US$1.2 trillion in dollar holdings to other currencies in the next five years, Merrill Lynch & Co economists say.

"The dollar will not recover completely its dominant role in the system, although it may well share that role with the euro and even the pound," says Kenen, a former Treasury adviser. "What some of us thought could happen in the distant future may be upon us now."

Lester Thurow, a professor of economics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, disputes the assertion that the dollar has lost its clout. Historical trends of developing nations suggest China's economic output and per-capita income may not catch up to the US's for about a century.

"A reserve currency needs to be the currency of a world power," Thurow says. "China may pass the US, but not until 2100."

China, with US$1.46 trillion in foreign exchange reserves, is a wild card. Its financial leaders are combing the world's markets for investments that pay more than the return of about 4 percent on 10-year US Treasury bonds.

Chinese investors reduced their holdings of U.S. Treasuries by 8 percent to US$388.1 billion in October from a peak in March. Then, early this month, China's Ministry of Commerce gave a boost to the dollar, saying it would encourage more businesses to buy US assets.

Morgan Stanley, the second-largest US securities firm, on Wednesday said it received a US$5 billion infusion from the state-controlled China Investment Corp. The firm lost US$3.56 billion in the fourth quarter amid the subprime mortgage market collapse.

Economists debate whether the administration of US President George W. Bush wants the dollar to appreciate. After US trading partners in Europe and Japan criticized the currency's decline, US Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson last month stepped up his rhetoric about the economy's long-term growth prospects to instill confidence in the dollar, says Jens Nordvig, an economist at Goldman Sachs Group Inc in New York.

With the weak dollar spurring US exports -- one of the few bright spots in the economy -- some economists don't take Paulson at his word.

"The Bush administration is not sincere in saying it wants a strong dollar," says Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson, a professor emeritus at MIT. "The long-run trend for the dollar is very likely to be downward."

The currency will be barred from more places than the Taj Mahal in the event Samuelson is right.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion