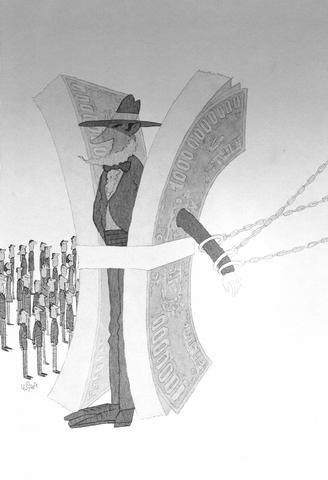

The falling US dollar has emerged as a source of profound global macro-economic distress. The question now is how bad that distress will become. Is the world economy at risk? There are two possibilities. If global savers and investors expect the US dollar's depreciation to continue, they will flee the currency unless they are compensated appropriately for keeping their money in the US and its assets, implying that the gap between US and foreign interest rates will widen. As a result, the cost of capital in the US will soar, discouraging investment and reducing consumption spending as high interest rates depress the value of households' principal assets: their houses.

The resulting recession might fuel further pessimism and cutbacks in spending, deepening the downturn. A US in recession would no longer serve as the importer of last resort, which might send the rest of the world into recession as well. A world in which everybody expects a falling US dollar is a world in economic crisis.

By contrast, a world in which the US dollar has already fallen is one that may see economic turmoil, but not an economic crisis. If the US dollar has already fallen -- if nobody expects it to fall much more -- then there is no reason to compensate global savers and investors for holding US assets.

On the contrary, in this scenario there are opportunities: the US dollar, after all, might rise; US interest rates will be at normal levels; asset values will not be unduly depressed; and investment spending will not be affected by financial turmoil.

Of course, there may well be turbulence: When US wage levels appear low because of a weak US dollar, it is hard to export to the US, and other countries must rely on other sources of demand to maintain full employment. The government may have to shore up the financial system if the changes in asset prices that undermined the US dollar sink risk-loving or imprudent lenders.

But these are, or ought to be, problems that we can solve. By contrast, sky-high US interest rates produced by a general expectation of a massive ongoing US dollar decline is a macroeconomic problem without a solution.

Yet so far there are no signs that global savers and investors expect a US dollar decline. The large gap between US and foreign long-term interest rates that should emerge from and signal expectations of a falling US dollar does not exist. And the US$65 billion needed every month to fund the US current-account deficit continues to flow in. Thus, the world economy may dodge yet another potential catastrophe.

That may still prove to be wishful thinking. After all, the US' still-large current-account deficit guarantees that the US dollar will continue to fall. Even so, the macroeconomic logic that large current-account deficits signal that currencies are overvalued continues to escape the world's international financial investors and speculators.

On one level, this is very frustrating: We economists believe that people are smart enough to understand their situation and capable enough to pursue their own interests. Yet the typical investor in US dollar-denominated assets -- whether a rich private individual, a pension fund, or a central bank -- has not taken the steps to protect themselves against the very likely US dollar decline in our future.

In this case, what is bad for economists is good for the world economy: We may be facing a mere episode of financial distress in the US rather than sky-high long-term interest rates and a depression. The fact that economists can't explain it is no reason not to be thankful.

J. Bradford DeLong, professor of economics at the University of California at Berkeley, was assistant US Treasury secretary during the Clinton administration.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its