The rolling thunder of an oncoming monsoon storm provided the appropriate soundtrack to Ratanak Akthun's entrance into the ring.

The self-assured young fighter eyed his opponent, Puth Khemarak, who seemed less solid and a little dazed by the applause that greeted his own entrance into the gymnasium in Phnom Penh's Olympic Stadium.

Their clash was to be the first full-contact fight of last month's National Bokator Championships and the crowd, made up of students from opposing fighting schools, clapped and shouted itself into a frenzy.

Cambodia's ancient martial art of bokator is enjoying a sudden revival after centuries of neglect and its near extinction under the communist Khmer Rouge regime, which outlawed the practice and murdered its masters.

But practitioners are struggling for legitimacy and purists say a younger generation's fascination with foreign martial arts is threatening this symbol of the country's past military might.

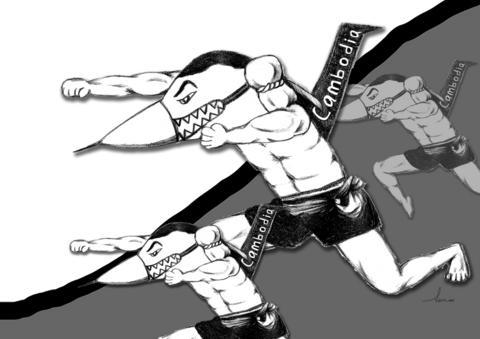

More an art form than a sport, bokator -- which literally means "lion fighter" in Cambodian -- has been somewhat derisively described as a dance with a little bit of fighting thrown in for effect.

This is not entirely untrue. Those who have mastered the thousands of punches, sweeping high kicks, take-downs and feints have a fluid animal grace that lulls the spectator into forgetting that this is a seriously dangerous fighting form.

But then erupts a violence that is found in few fighting rings. Like Saturday night brawlers, nearly bare-knuckled bokator fighters pummel, stomp and throttle each other into submission.

Ratanak Akthun's earlier cockiness could not save him from a crushing kick that broke ribs and sent him to a humiliating, semi-conscious departure from the ring.

The next two full-contact matches ended just as abruptly in knock-outs.

The championships last month were only the second ever to be held and were the result of one man's singular crusade not just to return bokator to Cambodia, but also to introduce it to the rest of the world.

Sean Kim San, a bokator grandmaster and founder of the Cambodian Yuthkun Federation, returned from the US in the 1990s and in 2004 opened a school to teach the craft to a new generation of Cambodians otherwise fed a diet of Thai kickboxing and Western professional wrestling.

"We had been sleeping for 1,000 years, but 2004 was the new birth for bokator," the 62-year-old master said.

Speaking recently in the converted space above a parking garage that he shares with several other martial arts schools, Sean Kim San took out a few vinyl folders that he said are the sport's bible.

Inside he is creating, in painstaking detail, an index of the hundreds, if not thousands of moves that must be mastered at each level of bokator.

"Before there was nothing," he said, explaining that before he took up his quest to revive bokator, knowledge of the fighting form lay scattered across the country among its few surviving yet reluctant masters.

Scenes of bokator are carved into the walls of the Angkor temples, inextricably linked to a rich cultural heritage that goes back many hundreds of years.

But the Khmer Rouge who seized control of the country in 1975 and unleashed one of the 20th century's most devastating upheavals, inexplicably sought to destroy bokator along with every other vestige of modern Cambodia.

Most of its practitioners were among the two million left dead by the time the regime was overthrown in 1979, and those still alive hid their talents out of fear, Sean Kim San said.

"The Khmer Rouge -- everything interesting they destroyed," he said, adding that after his return to Cambodia he unearthed about a dozen elderly bokator masters.

"But they were still scared about the killings, about Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge -- they were afraid to speak the truth," he said.

Still, he pieced together this puzzle, logging each swing or kick into his catalogue of bokator moves and slowly rebuilding interest in the ancient form.

Three years ago, he said he had only seven students in one school. Now more than 1,000 practice bokator in schools across 10 provinces.

"We have about 400 or 500 students here, including some foreigners," he said of his own gym at the end of a ramshackle Phnom Penh side street. "This is how far we've raised up the sport."

Mathew Olsen, an Australian instructor of the Korean martial art hapkido and a bokator convert, said he had not known Cambodia had its own martial art.

"I was surprised there was something with such a wide spectrum -- the weapons, the punches, kicks, the ground fighting and pressure points makes it very lethal," he said during a recent training session.

"Bokator is a very complete martial art, very interesting to foreigners," he said. "Basically I think there is more art in this martial art than a lot of other martial arts."

While one of Sean Kim San's hopes is to introduce bokator to the wider world -- and eventual inclusion in international martial arts competitions -- a larger and more immediate goal is to keep this very Cambodian tradition alive at home.

"It is very important to pass this from generation to generation because this is our blood. This was passed down from grand masters and our kings," he said.

He has a dream, he said, that bokator training will become a regular feature in Cambodian primary schools.

"That means millions and millions of people know very well bokator," he said.

Concerns that the US might abandon Taiwan are often overstated. While US President Donald Trump’s handling of Ukraine raised unease in Taiwan, it is crucial to recognize that Taiwan is not Ukraine. Under Trump, the US views Ukraine largely as a European problem, whereas the Indo-Pacific region remains its primary geopolitical focus. Taipei holds immense strategic value for Washington and is unlikely to be treated as a bargaining chip in US-China relations. Trump’s vision of “making America great again” would be directly undermined by any move to abandon Taiwan. Despite the rhetoric of “America First,” the Trump administration understands the necessity of

US President Donald Trump’s challenge to domestic American economic-political priorities, and abroad to the global balance of power, are not a threat to the security of Taiwan. Trump’s success can go far to contain the real threat — the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) surge to hegemony — while offering expanded defensive opportunities for Taiwan. In a stunning affirmation of the CCP policy of “forceful reunification,” an obscene euphemism for the invasion of Taiwan and the destruction of its democracy, on March 13, 2024, the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) used Chinese social media platforms to show the first-time linkage of three new

If you had a vision of the future where China did not dominate the global car industry, you can kiss those dreams goodbye. That is because US President Donald Trump’s promised 25 percent tariff on auto imports takes an ax to the only bits of the emerging electric vehicle (EV) supply chain that are not already dominated by Beijing. The biggest losers when the levies take effect this week would be Japan and South Korea. They account for one-third of the cars imported into the US, and as much as two-thirds of those imported from outside North America. (Mexico and Canada, while

The military is conducting its annual Han Kuang exercises in phases. The minister of national defense recently said that this year’s scenarios would simulate defending the nation against possible actions the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) might take in an invasion of Taiwan, making the threat of a speculated Chinese invasion in 2027 a heated agenda item again. That year, also referred to as the “Davidson window,” is named after then-US Indo-Pacific Command Admiral Philip Davidson, who in 2021 warned that Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) had instructed the PLA to be ready to invade Taiwan by 2027. Xi in 2017