By abandoning many of the nuclear arms agreements negotiated in the last 50 years, the US has been sending mixed signals to North Korea, Iran and other states with the technical knowledge to create nuclear weapons.

Proposed agreements with India compound this quagmire and further undermine the global pact for peace represented by the nuclear nonproliferation regime.

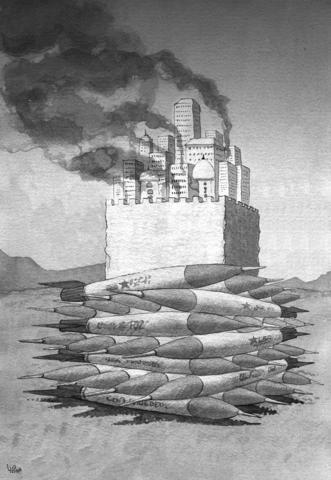

At the same time, no significant steps are being taken to reduce the worldwide arsenal of almost 30,000 nuclear weapons now possessed by the US, Russia, China, France, Israel, Britain, India, Pakistan and perhaps North Korea. A global holocaust is just as possible now, through mistakes or misjudgments, as it was during the depths of the Cold War.

The key restraining commitment among the five original nuclear powers and more than 180 other countries is the 1970 Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). Its key objective is "to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology ... and to further the goal of achieving nuclear disarmament."

In the last five-year review conference at the UN in 2005, only Israel, India, Pakistan, and North Korea were not participating -- the first three have nuclear arsenals that are advanced, while the fourth's are embryonic.

The US government has not set a good example, having already abandoned the Anti-Ballistic Missile treaty, binding limitations on testing nuclear weapons and developing new ones and a long-standing policy of foregoing threats of "first use" of nuclear weapons against non-nuclear states. These recent decisions have encouraged China, Russia and other NPT signatories to respond with similar actions.

Knowing since 1974 of India's nuclear ambitions, I and other US presidents imposed a consistent policy: no sales of nuclear technology or uncontrolled fuel to India or any other country that refused to sign the NPT.

Today, these restraints are in the process of being abandoned.

I have no doubt that Indian leaders are just as responsible in handling their country's arsenal as leaders of the five original nuclear powers. But there is a significant difference: the original five have signed the NPT and have stopped producing fissile material for weapons.

Indian leaders should make the same pledges and should also join other nuclear powers in signing the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. Instead, they have rejected these steps and insist on unrestricted access to international assistance in producing enough fissile material for as many as 50 weapons a year, far exceeding what is believed to be India's current capacity.

If India's demand is acceptable, why should other technologically advanced NPT signatories, such as Brazil, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Japan -- to say nothing of less "responsible" states -- continue to restrain themselves?

Having received at least tentative approval from the US for its policy, India still faces two further obstacles: an acceptable agreement with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and an exemption from the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), a 45-country body that -- until now -- has barred nuclear trade with any nation that refuses to accept international nuclear standards.

The non-nuclear NSG members are Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey and Ukraine.

The role of these states and the IAEA is not to prevent India's development of nuclear power or even nuclear weapons, but rather to assure that it proceeds as almost all other responsible countries on earth do, by signing the NPT and accepting other reasonable restraints.

Nuclear powers must show leadership, by restraining themselves and by curtailing further departures from the NPT's international restraints. One-by-one, the choices they make today will create a legacy -- deadly or peaceful -- for the future.

Jimmy Carter is a former president of the US. Copyright: Project Syndicate

Concerns that the US might abandon Taiwan are often overstated. While US President Donald Trump’s handling of Ukraine raised unease in Taiwan, it is crucial to recognize that Taiwan is not Ukraine. Under Trump, the US views Ukraine largely as a European problem, whereas the Indo-Pacific region remains its primary geopolitical focus. Taipei holds immense strategic value for Washington and is unlikely to be treated as a bargaining chip in US-China relations. Trump’s vision of “making America great again” would be directly undermined by any move to abandon Taiwan. Despite the rhetoric of “America First,” the Trump administration understands the necessity of

US President Donald Trump’s challenge to domestic American economic-political priorities, and abroad to the global balance of power, are not a threat to the security of Taiwan. Trump’s success can go far to contain the real threat — the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) surge to hegemony — while offering expanded defensive opportunities for Taiwan. In a stunning affirmation of the CCP policy of “forceful reunification,” an obscene euphemism for the invasion of Taiwan and the destruction of its democracy, on March 13, 2024, the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) used Chinese social media platforms to show the first-time linkage of three new

If you had a vision of the future where China did not dominate the global car industry, you can kiss those dreams goodbye. That is because US President Donald Trump’s promised 25 percent tariff on auto imports takes an ax to the only bits of the emerging electric vehicle (EV) supply chain that are not already dominated by Beijing. The biggest losers when the levies take effect this week would be Japan and South Korea. They account for one-third of the cars imported into the US, and as much as two-thirds of those imported from outside North America. (Mexico and Canada, while

I have heard people equate the government’s stance on resisting forced unification with China or the conditional reinstatement of the military court system with the rise of the Nazis before World War II. The comparison is absurd. There is no meaningful parallel between the government and Nazi Germany, nor does such a mindset exist within the general public in Taiwan. It is important to remember that the German public bore some responsibility for the horrors of the Holocaust. Post-World War II Germany’s transitional justice efforts were rooted in a national reckoning and introspection. Many Jews were sent to concentration camps not