Anyone attempting to take a train to or from the southwest of England last weekend could be forgiven for wondering if they had accidentally strayed on to the set of a disaster movie -- or perhaps an episode of the BBC's recent exercise in futurology, If. Trains appeared on boards and then simply vanished. Announcers on the London Underground pronounced litanies of lines progressively going out of service. As for those who had to watch their homes and businesses succumb to the rising tide, among them there was a general sense of disbelief. Disbelief that a downpour so short should wreak such havoc, disbelief that such scenes should be occurring at all.

The disbelief is justified. This, after all, is a country famed for its wetness. Rain is our national weather. Snow -- well, we all know what happens when Britain is dusted with a few millimeters of snow. Excessive heat, like last summer's, causes difficulties, too -- but rain? Given our extensive experience, surely we should lead the world in rain management.

Alas, it seems not. Thousands had to be evacuated last weekend, thousands more were trapped in their homes. That's thousands to add to those still unable to go home after floods in the north of England last month, which killed eight people -- and untold millions to add to a national insurance bill eventually expected to top ?2.5 billion (US$5.1 billion). Evesham, in Worcestershire, in central England, the worst-hit town last weekend, experienced floods of up to five metres.

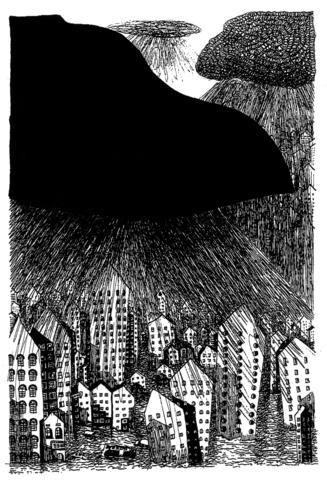

illustration: mountain people

All are entitled to ask how such relatively short bursts of rain -- just one hour in London, somewhat longer in places such as Oxfordshire -- could have such devastating results.

In fact, the answer lies partly in how quickly it all happened. Brize Norton in Oxfordshire received 121.2mm of rain between midnight on July 19 and 5pm on July 20 -- a sixth of what it would expect for the whole year. Further north, South Yorkshire got a month's worth of rain on June 25.

"It's extremely unusual to have such a high depth of rainfall in such a short duration," said Adrian Saul, research director of the Pennine Water Group at Sheffield University, South Yorkshire, an expert in urban drainage systems and one of the authors of the 2004 Flood and Coastal Defence Project, the most wide-ranging analysis of future flood risk ever conducted in the UK.

He also points out that prevailing pressure systems have been dropping rain on to the country for weeks now, "and the ground is very wet, so immediately you get rainfall, you get runoff."

It isn't just a case of the ground not being able to absorb so much so fast -- drainage systems can't either, and have simply been overwhelmed.

"When you design a system you have to take a level of risk, and generally the level of risk is sufficient to protect our communities," Saul said. "But once the design criteria have been beaten, the systems become overwhelmed and the defenses are overtopped. It's very fortunate that the Victorians built the systems as big as they did. In London in particular, [they] had the foresight to see that there would be change and it's protected London ever since."

Which is, of course, impressive, and true, but it is also true that they were built when London's population was a quarter of what it is now -- and on July 20, they simply didn't hold up.

"Our sewers are not designed to deal with that capacity of water flowing through them," said Nicola Savage, a spokeswoman for Thames Water, the utility which supplies the British capital.

They are also not designed for the way we currently treat them. We each, personally, use far more water than ever before.

There is also "a tendency for the public to use the sewers as a litter bin," Savage said.

People flush nappies down toilets, sanitary products, tights; in particular "we need to encourage people not to be pouring stuff down the sink -- for example, fat, oil and grease. The sewers were never designed to cope with this sort of material. They were only ever designed for rainwater and foul water," she said.

Fat, liquid when it's hot and poured away by fast-food outlets, for example, coagulates as it cools.

"Increasingly, our sewer flushers' time is being taken up clearing deposits of fat, oil and grease out of the sewers, which is obviously impeding the free flow of liquid through them," Savage said.

The arteries of the city of London, it seems, are furred with cholesterol, and its citizens are suffering the consequences.

Thames Water says that it is spending ?323 million upgrading its sewers but, as Jean Venables, chief executive of the Association of Drainage Operators, puts it, carefully, large-scale investment in sewers has not generally been the order of the day in this country.

"There is a need for the water companies to be allowed ... to invest not only in replacing the drains because they've come to the end of their life, but also to extend the system to cope with the new development that's taking place, and our increased use of water. Until recently, Ofwat [the economic regulator for the water and sewerage industry in England and Wales] has been reluctant to allow very much investment by water companies, because they wanted to keep water bills down," Venables said.

Partly as a result of his work on the Foresight report, Saul has for the past three years been involved in ?5.6 million project called the Flood Risk Management Research Consortium, which is attempting to come up with both short and long-term solutions to a problem that climate change means will only get worse.

Saul manages research into urban flood risk and is attempting to come up with mathematical models that might predict the potent interactions of surface, sewer and river flows that cause urban flash floods -- "trying to better understand how we can manage the floods, channel them away from urban areas."

But overloaded urban drainage systems are only one of a complex set of reasons why we have been overwhelmed with water. The consortium is also looking into land use management -- essentially, how farmers can control the flow of water off land, which can be affected by all sorts of things. The direction a farmer ploughs, for example -- if he or she goes across hills rather down them -- can decrease runoff. Strategically placed trees can trap it. Stocking levels can be adjusted -- the more animals there are on a piece of land, the more they pack the ground down, and the less able it is to absorb water.

"Stocking densities and drainage patterns have been changed already [in response to the floods in the north last month]," Venables said, "particularly in upland areas."

Unfortunately, this hasn't happened soon enough to avoid "a considerable amount of crop damage," he said.

At the moment farmers in some areas can't access their crops to see if they might be salvageable, and "that's going to be showing up very quickly in our shops," he said.

Earlier this month the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals spoke of growing fears for intensively farmed animals -- no drinking water for 48 hours will mean widespread livestock death, which might also in turn affect the price of food.

The consortium, which will soon learn whether it has secured more funding with which to continue its work, is also looking at the infrastructure of British rivers -- whether embankments are high enough, whether there are ways to divert floods when they occur -- and attempting to use modelling to predict how floods move and change the landscape. (When a river floods, for example, the topography of the river bed changes, and thus the behavior of the river changes.)

It is also looking at small-scale ways in which individuals can help reduce a problem that, in fact, they have helped create -- adding extensions to houses, paving driveways, car parks -- all of this activity decreases the amount of soft ground that water can disappear into, and increases the amount of runoff into drains and rivers.

"In essence, the latest thinking is that anything that runs off the house should be stored locally," Saul said.

This can mean rainwater harvesting systems, which ensure that rainfall doesn't go straight into the sewerage system; it can be collected -- in storage tanks under driveways, for example -- and used to flush toilets or run washing machines or regulate the sewerage system. Small trenches, called soakaways, can be dug in gardens and filled with stones, which trap the water and release it into the ground a bit more slowly. Every little bit helps.

For the fact remains that while what Britain has experienced over the past month is, as experts keep pointing out, a series of freak weather events, our changing climate means that there may well be more of them, more frequently.

This past week Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire were having to rush to the barricades, to get out the sandbags and evacuate the citizens. Tomorrow, next month, next year -- who knows?

The international women’s soccer match between Taiwan and New Zealand at the Kaohsiung Nanzih Football Stadium, scheduled for Tuesday last week, was canceled at the last minute amid safety concerns over poor field conditions raised by the visiting team. The Football Ferns, as New Zealand’s women’s soccer team are known, had arrived in Taiwan one week earlier to prepare and soon raised their concerns. Efforts were made to improve the field, but the replacement patches of grass could not grow fast enough. The Football Ferns canceled the closed-door training match and then days later, the main event against Team Taiwan. The safety

There are moments in history when America has turned its back on its principles and withdrawn from past commitments in service of higher goals. For example, US-Soviet Cold War competition compelled America to make a range of deals with unsavory and undemocratic figures across Latin America and Africa in service of geostrategic aims. The United States overlooked mass atrocities against the Bengali population in modern-day Bangladesh in the early 1970s in service of its tilt toward Pakistan, a relationship the Nixon administration deemed critical to its larger aims in developing relations with China. Then, of course, America switched diplomatic recognition

The National Immigration Agency on Tuesday said it had notified some naturalized citizens from China that they still had to renounce their People’s Republic of China (PRC) citizenship. They must provide proof that they have canceled their household registration in China within three months of the receipt of the notice. If they do not, the agency said it would cancel their household registration in Taiwan. Chinese are required to give up their PRC citizenship and household registration to become Republic of China (ROC) nationals, Mainland Affairs Council Minister Chiu Chui-cheng (邱垂正) said. He was referring to Article 9-1 of the Act

Strategic thinker Carl von Clausewitz has said that “war is politics by other means,” while investment guru Warren Buffett has said that “tariffs are an act of war.” Both aphorisms apply to China, which has long been engaged in a multifront political, economic and informational war against the US and the rest of the West. Kinetically also, China has launched the early stages of actual global conflict with its threats and aggressive moves against Taiwan, the Philippines and Japan, and its support for North Korea’s reckless actions against South Korea that could reignite the Korean War. Former US presidents Barack Obama