Yesterday, US President George W. Bush was set to -- reluctantly -- announce a new policy for the US in Iraq. A new policy is needed not only to halt the US' drift into impotence as it tries to prevent Iraq from spiraling into full-scale civil war, but also because the map of power in the Middle East has changed dramatically.

That map has been in constant flux for the last 60 years, during which the main players -- Egypt, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Israel, and Iran -- have formed and broken alliances. Now, something like a dividing line is emerging, and if Bush finally begins to understand the region's dynamics, he may be able to craft a policy with a chance of success.

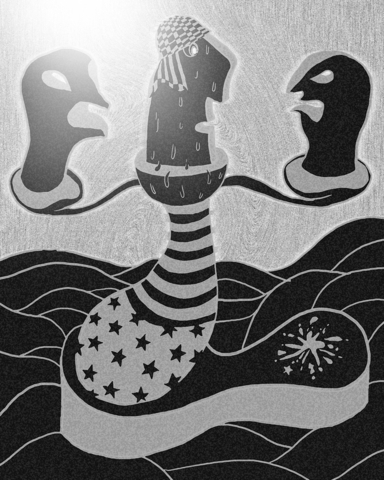

This regional realignment is typified by the emergence of a de facto alliance that dare not speak its name. Israel and Saudi Arabia, seemingly the most unlikely of allies, have come together to contain their common enemy: Iran, with its mushrooming influence in Iraq, Lebanon and Palestine. Iran not only threatens Israel (and the region) with its desire for a nuclear capability and its Shiite proxy militants; it is also seeking to usurp the traditional role of moderate Sunni Arab regimes as the Palestinians' defenders.

After decades of using concern for the Palestinian cause to shore up popular support for their own ineffective and undemocratic regimes, these moderate Arab leaders have now been put on the defensive by Iran's quest for hegemony. If Iran succeeds in being seen as the genuine patron of Palestinian national aspirations, it will also succeed in legitimizing its claim for dominance in the Middle East.

Israel, a country in shock following its failure to destroy Hezbollah last summer, and humiliated by Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's vow to "wipe Israel off the map" -- a threat backed up by Iran's support of Hamas and Hezbollah -- now talks about a "quartet of moderates" as the region's only hope. Indeed, Israel now sees its security as relying not so much on a US guarantee, but on Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and Turkey (which is seeking regional influence in fear of rejection by the EU) restraining Iran and its paid proxies. According to Israeli Vice Premier Shimon Peres, Israel hopes to isolate and contain the Shiite/Farsi spheres of power by forging open cooperation with the Sunni/Arab domain.

Saudi Arabia is just as eager to contain the Iranian threat and the growing "Shiite crescent" that, with the empowerment of the Shiites in Iraq, has moved westward to begin to include the Shiite regions of the Kingdom. So it should be no surprise that the Saudi regime was the first to condemn Shiite Hezbollah at the start of the war with Israel, and that it announced last month that it would support Iraq's Sunnis militarily should a precipitate US withdrawal incite a Sunni/Shiite civil war there.

The Shiite threat to the Saudi government is ideological. Indeed, it goes to the heart of the Saudi state's authority, owing to the Al Saud royal family's reliance on Wahhabi Islam to legitimate its rule. Since the Wahhabis consider the Shiite apostates, the challenge from the Shiites -- both within and without Saudi Arabia -- represents a mortal threat.

So Saudi Arabia is ready to cooperate with Israel not only against Iran, but also against other "radicals," such as Hamas. Remarkably, Palestine's Hamas prime minister, Ismael Haniyeh, was not received in Saudi Arabia last month, when he was traveling through the region pleading for support for his beleaguered government. Conservative Saudi Arabia prefers dealing with traditional and predictable leaders, such as Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas and Lebanon's Prime Minister Fouad Siniora, rather than firebrand populist leaders like Hezbollah's Hassan Nasrallah, Hamas' Khalid Meshal and Iran's Ahmadinejad.

Last year, Saudi Arabia's King Abdullah, worried by Shiite expansionism, was persuaded by Prince Bandar bin Sultan, the head of his National Security Council, to coordinate policy with Israel to counter Iran's growing influence. Israel, after all, is a "reliable enemy" for Saudi Arabia, having destroyed Nasser's Egyptian army in 1967 -- a time when the Saudis were fighting Egypt by proxy in Yemen. So Prince Turki al-Faysal, the long time head of Saudi intelligence, has met with Meir Dagan, the head of Israel's Mossad, while Bandar met with Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert in Jordan the same month.

Yet covert support from Israel, the US and the Saudis for Abbas and Siniora does little to help them in their domestic battles. From Morocco, Algeria, Libya and Sudan to Bahrain and Yemen -- indeed, throughout the Muslim world from Jakarta to Nigeria -- Islamic radicals have won the popularity sweepstakes. A recent poll in Egypt ranked Nasrallah, Meshal and Ahmadinejad as the three most popular figures. This leads to an unavoidable dilemma: Bush will have to choose between supporting democracy and backing those who want to fight Islamic radicalism.

Yet Israel, the US and the region's moderates can benefit from the deepening schism in the Arab/Muslim world. That schism is being consolidated by Saudi support of all the region's Sunni Muslims. It is this sense of "Sunni solidarity" that is becoming the decisive factor in the war for the soul of Islam, and in the struggle for mastery in the Middle East that is now underway.

Mai Yamani is an author and broadcaster. Her most recent book is Cradle of Islam.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

Donald Trump’s return to the White House has offered Taiwan a paradoxical mix of reassurance and risk. Trump’s visceral hostility toward China could reinforce deterrence in the Taiwan Strait. Yet his disdain for alliances and penchant for transactional bargaining threaten to erode what Taiwan needs most: a reliable US commitment. Taiwan’s security depends less on US power than on US reliability, but Trump is undermining the latter. Deterrence without credibility is a hollow shield. Trump’s China policy in his second term has oscillated wildly between confrontation and conciliation. One day, he threatens Beijing with “massive” tariffs and calls China America’s “greatest geopolitical

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairwoman Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) made the astonishing assertion during an interview with Germany’s Deutsche Welle, published on Friday last week, that Russian President Vladimir Putin is not a dictator. She also essentially absolved Putin of blame for initiating the war in Ukraine. Commentators have since listed the reasons that Cheng’s assertion was not only absurd, but bordered on dangerous. Her claim is certainly absurd to the extent that there is no need to discuss the substance of it: It would be far more useful to assess what drove her to make the point and stick so

The central bank has launched a redesign of the New Taiwan dollar banknotes, prompting questions from Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislators — “Are we not promoting digital payments? Why spend NT$5 billion on a redesign?” Many assume that cash will disappear in the digital age, but they forget that it represents the ultimate trust in the system. Banknotes do not become obsolete, they do not crash, they cannot be frozen and they leave no record of transactions. They remain the cleanest means of exchange in a free society. In a fully digitized world, every purchase, donation and action leaves behind data.

A large majority of Taiwanese favor strengthening national defense and oppose unification with China, according to the results of a survey by the Mainland Affairs Council (MAC). In the poll, 81.8 percent of respondents disagreed with Beijing’s claim that “there is only one China and Taiwan is part of China,” MAC Deputy Minister Liang Wen-chieh (梁文傑) told a news conference on Thursday last week, adding that about 75 percent supported the creation of a “T-Dome” air defense system. President William Lai (賴清德) referred to such a system in his Double Ten National Day address, saying it would integrate air defenses into a