Latin America, as the late Venezuelan author Carlos Rangel once wrote, has always had a "love-hate relationship" with the US. The love is expressed in its purest form: imitation. The hate -- more akin to resentment -- boils down to a frustrated desire to get Washington's attention.

Cuba's Fidel Castro pulled it off in the 1960s, torturing the Kennedy brothers with his cigar and his Marxism; and now, in Venezuela, President Hugo Chavez is giving us a rerun. At least, this is the refrain of Nikolas Kozloff, a British-educated American who has written Hugo Chavez: Oil, Politics, and the Emerging Challenge to the United States.

Kozloff apparently believes that Americans have much to fear from Venezuela. His admiring study of Chavez, an up-by-the-bootstraps lieutenant colonel who tried and failed to take power in a coup and subsequently succeeded at the ballot box, is peppered with phrases like "in an alarming warning sign for George Bush," and, "in an ominous development for [US] policy makers."

Why does Kozloff think, as stated on the book jacket, that Venezuela represents a "potentially dangerous enemy to the [US]?" Caracas is the US' fourth-biggest oil exporter, so maybe some day, the implication is, it could cut us off.

And Chavez, with his friend you-know-who in Cuba, has taken to taunting the US and lobbying other Latin American countries against the brand of free-trade liberalism that Washington has advocated. Chavez has even been trying to form an energy alliance with Argentina and Brazil, for the ostensible purpose of using oil as a "weapon" against the gringos, and he has refused to permit US overflights in the war against cocaine.

Is this really worth getting all steamed up about? I lived in Venezuela during the 1970s, also a period of high oil prices and, not coincidentally, a time when the government was strutting its stuff as a regional (and vaguely anti-capitalist) power. Getting the US to worry -- or minimally to care -- was a high priority, as I realized when a friendly Venezuelan reporter eagerly asked me which of two left-wing political parties Americans "feared the most."

One of these parties was known by the acronym MIR and the other as MAS. The truth was that no Americans I knew had heard of either. My own relatives could barely distinguish Venezuela from Colombia or Peru. I didn't say that, of course. The local journalists were unfailingly kind to me, and I had no wish to hurt their feelings. I allowed, "I guess we fear each of them about the same." Anyway, in a few years, the price of oil collapsed, and the posturing from Caracas went with it.

Kozloff will perhaps appreciate the personal anecdote because his book is replete with them. He lets us in on his travels, Kerouac-style, so we are with him when he is hiking in the Andes, observing rural poverty, or acquainting himself with indigenous tribes.

Then the author is back in England, where he joins an "anti-capitalist May Day protest," at which one of his confreres defaces a statue of Winston Churchill. Then he is watching Chavez on TV, then protesting against globalism, then, in 2000, doing research for his dissertation in Caracas. He watches Al Gore and George Bush on the tube, cannot see much difference between them and casts his lot with Ralph Nader.

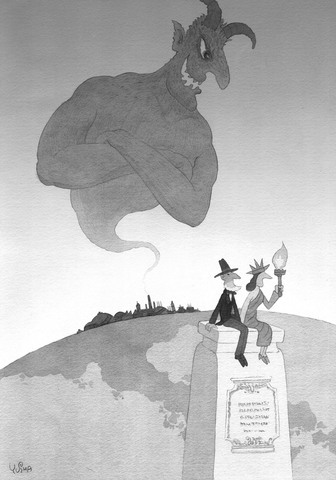

As for Chavez, the author portrays him, convincingly, as a soldier indignant about the moral flabbiness and corrupt ways of the career politicians he replaced. We learn that Chavez's antipathy toward American culture stems, in some measure, from his partly Indian blood lines. So it is that Chavez, a phrase maker to be sure, has rechristened Columbus Day "Indigenous Resistance Day." Resistance to what? He is no fan of liberal economics, free trade, cross-border investment, the prescriptions of the IMF nor, indeed, of capitalism itself.

This is all well and good with Kozloff. His analysis is essentially Marxist -- he sees trade as a one-way street that helps the rich and hurts the poor. His book is filled with the sort of new-lefty rhetoric I had thought went out in the 1970s. He applauds the Venezuelan president's idea for an alternative trade association -- meaning one not aligned with the US -- that, in Chavez's tedious phraseology, would be a "socially oriented trade bloc rather than one strictly based on the logic of deregulated profit maximization."

But neither Kozloff nor Chavez can escape the fact that the 1970s are over. Socialism hasn't worked; it's kaput. Free-market medicine (which Kozloff refers to by the more sinister-sounding "neo liberalism") hasn't always worked, but it's worked better than anything else.

And in fact, Kozloff's fantasy of a US threatened by left-wing Latinos is a vestige of a world that was dominated by a Moscow-Washington rivalry -- a world that no longer exists. The only way Venezuela could truly stop supplying the US with oil (which trades in a global market) would be to stop selling it to everyone, which isn't in the cards.

The right question to ask is not what the US has to fear from Chavez, but rather what Venezuelans have to fear from Chavez. The answer would seem to be plenty. He has militarized the government, emasculated the country's courts, intimidated the media, eroded confidence in the economy and hollowed out Venezuela's once-democratic institutions.

Chavez's rhetoric has provided a pleasing distraction to the country's poor, but it has not eradicated poverty. The real riddle of Venezuela today, as it was a generation ago, is why, despite its bountiful oil reserves, its fertile plains and its democratic traditions, it has been persistently unable to make an economic leap similar to that of Chile or of the various success stories in Asia. And writers who serve as cheerleaders for the failed idea of blaming the US are anything but Venezuela's friends.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its