Few views of China's spectacular economic growth could be more impressive than the one offered by the property company Tomson Riviera in Shanghai. From the top floor of its sleek, luxury apartment blocks in the Pudong development zone, you can, say the brochures, look out across the Huangpu river at one of the world's most futuristic skylines.

The panorama does not come cheap. At 180 million yuan (US$22 million) for a penthouse, this is the most exclusive residential complex in the country. Unfortunately for the developers, it is also the emptiest.

Since it opened in October last year, the waterfront development has failed to attract a single buyer for any of its 74 apartments. The situation is so desperate that Tomson has decided to put a second block out to global public tender.

Even so, the price is unlikely to rise for several years. Analysts blame an optimistic initial valuation of US$15,500 peer square meter. Others point to a housing market swamped with swanky apartment blocks and luxury villas. In a single week last month, residential prices in Shanghai fell 10 percent.

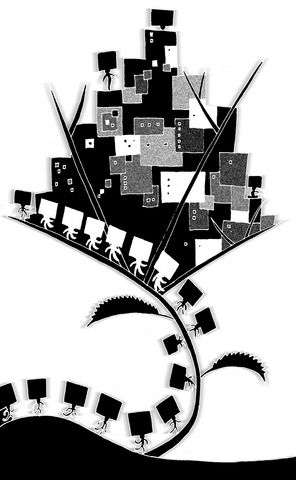

But there is another, darker explanation doing the rounds: that Tomson Riviera is the victim of a Chinese economy that is out of control. Unbalanced, overheated and wobbling on the shaky foundations of a debt-ridden banking system, the economy, say some doom-mongers, is heading for a fall.

It is not the first time such predictions have been heard. Since the start of the opening and reform policy in 1978, pessimists have intermittently warned that an average annual growth rate of 9 percent was unsustainable and would end in collapse. So far they have been wrong. China has not only maintained stable growth, it is accelerating.

On Tuesday, government figures revealed that the number of mobile phone customers in the country, already the world's biggest telecoms market, had grown to more than 431 million in the past year, up 45 percent.

But how fast is too fast? The question is once again being asked, and not just by the perennial pessimists. In a survey published last month in the respected Caijing magazine, 56 percent of Chinese economists saw signs of overheating, up from 15 percent in April.

After the latest quarterly GDP figures revealed an 11.3 percent surge, even President Hu Jintao (

But although the Chinese economy is growing more than twice as fast as Japan's did during its "bubble" heyday in the late 1980s, Beijing's problem is one of balance more than speed. Developing countries tend to grow rapidly as they catch up with rich countries. With a huge population that is still extremely poor by global standards, China has plenty of ground to make up.

China is unusual in many ways. It is the largest ever developing country; it is the largest country to make the transition from a command economy to a market. It is also ageing fast, and lastly it exports capital to the rest of the world rather than importing it. Where it is similar to other developing economies in the past is that there are distinct signs of overinvestment and wasted resources on a colossal scale.

The US industrialized rapidly in the 19th century, but it suffered periodic, painful and relatively short-lived boom-bust cycles as investors speculated wildly on often uneconomic projects. China, it is feared, could be on the brink of something similar: a savage but temporary slowdown that will not affect the country's long-term growth prospects.

The National Development and Reform Commission, the pilot of China's economy, noted with alarm recently that fixed asset investment increased 29.8 percent in the first six months of the year. In the car and textiles sectors, the increase was more than 40 percent.

The trigger for a crash could be a period of weakness in the US, the main customer for low-priced goods from Chinese factories. Exports and fixed investment account for more than 80 percent of China's GDP, and any sudden fall in US demand would feed through into factory closures and higher unemployment in China. The initial shock would, it is feared, be compounded by a financial crisis as it brought to light numbers of under-performing bank loans.

In the short term, the government would throw money at the problem by expanding public spending. In the longer term, the solution would be to expand consumption -- the mainstay of developed economies but a poor third behind investment and exports in China.

According to the commerce ministry, domestic supply exceeds demand for about 70 percent of consumer goods. The gap is evident at many of the new shopping centers. In Beijing's Golden Resources Mall, whose owners claimed it was the biggest in the world when it was opened in 2004, sales staff far outnumber customers. Half of the restaurants have closed, so has the spa and beauty salon. Several chain stores have moved out.

"Business isn't what we expected," said a sales clerk at the Lancel outlet. The French handbag shop has a turnover of about US$28,000 a month.

"We've been open two years, but there has been no improvement," the clerk said.

The mall's management company had to abandon a plan to open a car center because the market is so glutted that prices have nosedived. China's factories can turn out 2 million more cars than needed.

The mismatch between what the economy can produce and what it consumes has resulted in a big current account surplus and trade tensions with the EU over items such as bras, shoes and pull-overs, and with the US over everything from textiles to steel.

In June, China's monthly trade surplus hit a record US$14.5 billion, putting the country on course to surpass last year's record US$100 billion annual trade surplus. With money flowing in from all over the world, China overtook Japan this summer as the country with the world's largest foreign exchange reserves. By the end of the year, its holdings are expected to pass US$1 trillion.

The government is worried that the flood of money washing into an already loose credit system will add to the glut of villa developments, shopping malls, steel mills and car plants. It has ordered banks to tighten their lending policies and instructed local governments, a major driver of investment and development, to slow the allocation of land for new projects.

Most analysts believe that these measures will have to be supplemented by an appreciation of the yuan exchange rate, which was partially unpegged from the dollar last year, and still dearer borrowing. But the impact of monetary policy is uncertain. Far more important and difficult is the task of reining in local authorities, which are addicted to expansion.

These municipalities are the wildest speculators in China's economy. Free from electoral pressures, provincial leaders are judged on the size and growth of their economies. Many also have the incentive of kickbacks to push development projects, whatever the impact on the environment and local people's rights, and often regardless of central government instructions.

With Beijing's grip on its provinces so shaky, the talk is once again of whether China can slow gently to a more sustainable level or whether it will crash.

Morgan Stanley, the investment bank, estimates June's 19.5 percent surge in industrial output was the strongest since China launched its reforms.

"The unbalanced growth model has now gone to excess," wrote Stephen Roach, economist and China expert at the bank. "The coming downshift in Chinese economic growth could well be a good deal bumpier than widely thought. The longer it waits, the bigger the bumps."

Stephen Green, of Standard Chartered Bank, believes the absence of inflation suggests China has room to grow even faster.

"I think the restructuring we've seen -- more private sector, more foreign investment, more openness -- plus efforts to sort out energy bottlenecks mean the economy can grow pretty fast without inflation. Why not 12 percent or higher?" he said.

Chinese policymakers argue that the problems of growth are best solved by more growth. So far, this has worked, but there are long-term limits to the approach.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion