Communism was behind some of the most mammoth economic disasters of the past century. This would be bad enough on its own, but the creed also claimed 100 million victims, a number greater that of all the wars in the 20th century. Meanwhile, a fifth of the world's population still lives under the yoke of communist regimes.

After escaping its own economic disasters from communist experiments, China is beginning to adopt the discredited theories and policies of a revived Keynesianism. As such, Beijing has traded class struggle and central planning for the dubious tools for the management of aggregate demand.

Like many of the advanced industrial economies, Beijing is showing signs of addiction to fiscal spending used for juicing current economic growth. Out of this has come growing deficits and ballooning public-sector debt that undermine China's long-term economic prospects.

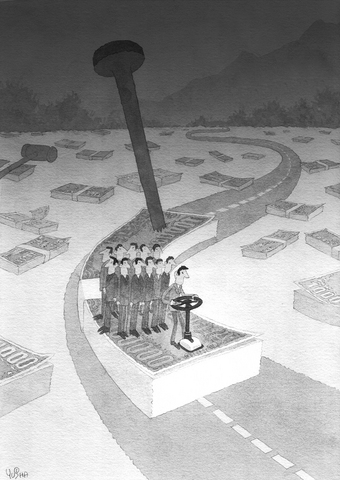

One of the forgotten lessons of the Keynesian-inspired stagflation of the 1970s is that economic growth based on increased government spending is unsustainable. It also introduces distortions and imbalances in the overall production structure of the domestic economy. And this is exacerbated by China's special problem of endemic corruption that has ensured that much of its investment has brought low-quality economic growth.

Much of the massive spending has gone into fixed-asset purchases of capital expenditures for local-government or state-owned enterprises (SOEs). For its part, the central government accounts for more than two-thirds of investment spending in China. Recently, such expenditures have outpaced GDP growth by a multiple of three.

Adding to the pressures to expand central government deficits are plans for funding an expanded social welfare program as well as the need to address obligations arising from reform of the banking sector. Like other countries caught in the sway of Keynesian thinking, Historically, Beijing's use of fiscal stimulus has pushed up its budget deficits and expands its outstanding debt that bodes ill for the future.

Besides Beijing's large and growing deficits, there are other contingent liabilities that will balloon existing public-sector debt. These include recapitalizing state-owned banks and fulfilling pension obligations. Other government debt and total bad debts held by SOEs could push the ratio of public-sector debt to GDP up to 70 percent.

China's leaders are taking a dangerous course by trading long-term costs in exchange for short-term gains that are likely to be illusory in the bestcase. The harsh reality of public-sector deficit spending is future generations of taxpayers must repay money spent badly today. This will mean slower future economic growth and fewer employment opportunities for today's youth.

But Beijing is making a familiar and "rational" political choice to spend beyond its means in reaction to new political pressures. Higher levels of state spending are also motivated by a nagging deflationary cycle and a fear of a slowdown in economic growth.

As it is, judging the merits of deficit spending is a bit muddled. While it gives the appearance of providing some positive short-term economic results, it is counter-productive in the long-term when the bills have to be paid.

The best evidence of the failure of Keynesian cures is found in Japan. After its "bubble economy" collapsed at the end of the 1980s, Tokyo financed its additional public-sector expenditures with fiscal deficits. Japan's public-sector spending during the 1990s exceeded ?800 trillion (US$7 trillion), an amount five times greater than America's fiscal expenditures during its restructuring in the 1980s.

Nonetheless, neither massive expenditures nor the expansionary credit policies with a zero-interest rate worked very well. In the end, average economic growth in Japan during the 1990s was only about 1.1 per cent.

However, Tokyo's outstanding debt rose from 56 percent of GDP at the beginning of the 1990s to about at least 130 percent. Many independent observers and credit-rating agencies put the figure at a much higher level.

What happened in Japan was that public officials were either unaware or wary of initiating the needed radical restructuring of the domestic economy. If Beijing follows Tokyo down a similar path, the Chinese economy will slow down markedly in the medium to long term.

There are similarities in the necessary restructuring for these two economies. Both Japan and China have large numbers of small and medium-sized enterprises that cannot gain access to capital. But industrial dinosaurs are kept on life lines from banks.

Both countries also have high levels of personal savings, but the funds are allocated poorly and are often guided by political expediency rather than economic logic. Japan and China also suffer from weak domestic capital markets so that most borrowing goes through the banking system.

The problem is that bank lending is subject to political pressures that often leads to inefficient outcomes. Politicized decisions on the use of capital are at the heart of the financial sector problems.

Since capital markets require greater transparency and accountability, massive failures tend to be less likely. Consequently, both countries would be well served if they allowed their domestic stock and bond markets to become wider and deeper.

China and Japan must go beyond cutting costs to execute their economic restructuring since reductions tend to be limited to fixing temporary problems. Complete restructuring involves a dynamic perspective to implement fundamental changes in management and the scope of government involvement in the economy.

Changes are needed in their respective corporate and political cultures in Beijing and Tokyo so that policies evolve to encourage real entrepreneurial initiatives in the private sector.

Christopher Lingle is senior fellow at the Center for Civil Society in New Delhi and visiting professor of economics at Universidad Francisco Marroquin in Guatemala.

If you had a vision of the future where China did not dominate the global car industry, you can kiss those dreams goodbye. That is because US President Donald Trump’s promised 25 percent tariff on auto imports takes an ax to the only bits of the emerging electric vehicle (EV) supply chain that are not already dominated by Beijing. The biggest losers when the levies take effect this week would be Japan and South Korea. They account for one-third of the cars imported into the US, and as much as two-thirds of those imported from outside North America. (Mexico and Canada, while

US President Donald Trump’s challenge to domestic American economic-political priorities, and abroad to the global balance of power, are not a threat to the security of Taiwan. Trump’s success can go far to contain the real threat — the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) surge to hegemony — while offering expanded defensive opportunities for Taiwan. In a stunning affirmation of the CCP policy of “forceful reunification,” an obscene euphemism for the invasion of Taiwan and the destruction of its democracy, on March 13, 2024, the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) used Chinese social media platforms to show the first-time linkage of three new

I have heard people equate the government’s stance on resisting forced unification with China or the conditional reinstatement of the military court system with the rise of the Nazis before World War II. The comparison is absurd. There is no meaningful parallel between the government and Nazi Germany, nor does such a mindset exist within the general public in Taiwan. It is important to remember that the German public bore some responsibility for the horrors of the Holocaust. Post-World War II Germany’s transitional justice efforts were rooted in a national reckoning and introspection. Many Jews were sent to concentration camps not

Deflation in China is persisting, raising growing concerns domestically and internationally. Beijing’s stimulus policies introduced in September last year have largely been short-lived in financial markets and negligible in the real economy. Recent data showing disproportionately low bank loan growth relative to the expansion of the money supply suggest the limited effectiveness of the measures. Many have urged the government to take more decisive action, particularly through fiscal expansion, to avoid a deep deflationary spiral akin to Japan’s experience in the early 1990s. While Beijing’s policy choices remain uncertain, questions abound about the possible endgame for the Chinese economy if no decisive