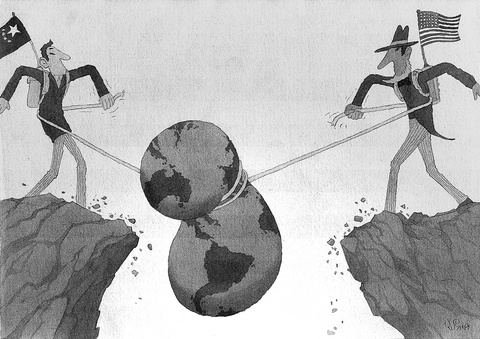

At the time of Sept. 11 and the invasion of Iraq, the US stood supreme with barely a challenge visible on any meaningful time horizon.

Almost five years on, we can clearly see both the inadequacies in the then-prevailing common sense, and the fallacies intrinsic to the neoconservative view of the world. There are, of course, always limits to power, even if they are not visible. The last five years have made the limits of US power plainly visible.

It is Iraq that has exposed those limits. The idea of US omnipotence always depended on its overwhelming military power, and the neoconservatives saw the latter as the key to a new era of US ascendancy. Iraq has demonstrated the limits of military power when it comes to subduing and governing a society. This failure has curbed the desire to intervene elsewhere: even if military action is contemplated in Iran, which now seems less likely, there will be no Iraq-style invasion and occupation.

The idea that Iraq would be a precursor to a new kind of US empire -- as advocated by Niall Ferguson, for example, in his book The Colossus -- is dead is subject to other limitations. What underpins power -- all kinds of power -- is economic strength, and in this respect the US is the subject of both a short-term crisis -- the twin deficits -- and a longer-term constraint, namely the fact that it accounts for a declining share of global GDP.

Iraq also demonstrated another profound shortcoming in the neo-conservative worldview. It was seen as both important in its own right, and as a means of reorganizing the Middle East. But this approach, magnified by the failure to subdue Iraq, led to an overwhelming preoccupation with the Middle East and, to a much lesser extent, central Asia, and the implicit relegation and neglect of US interests elsewhere. Perhaps superpowers always overreach themselves; arguably it is an occupational hazard. But history will surely judge the invasion of Iraq to have been a huge miscalculation and the moment when the geopolitical decline of the US, following the end of the Cold War, first became manifest.

In contrast to five years ago, the likely identity of the next superpower has become crystal clear. It is no longer just a possibility that it will be China; on the contrary, the probability is extremely high, if not yet a racing certainty. Nor does the timescale of this change have us peering into the distant future as it did five years ago. China is already beginning to acquire some of the interests and motivations of a superpower, and even a little of the demeanor. China feels like a parallel universe to the US, and certainly Europe. There is an expansive mood about the place. China is growing in self-confidence by the day.

And with good reason. There is no sign of China's economic growth abating, and it is this that lies behind its growing confidence. The massive contrasts between China and the US, both socially and economically, are enjoined in the argument over the US' trade deficit with China. The latter is deeply aware that its future prospects depend on the continuation of its economic growth and this remains its priority. But no longer to the exclusion of all else: China is beginning to widen its range of concerns and interests.

This has received most airplay in the context of China's search for secure supplies of oil and other commodities. To this end it has been acquiring a growing diplomatic presence in regions of the world like Africa and Latin America, making the US increasingly nervous about China's intentions.

This is understandable. China's growing economic clout and connections mean that it will increasingly offer an alternative to the US as an economic partner, and China is making it perfectly plain that it will not insist on the same kind of political strings as the US. We are only at the beginning of what will over time become a growing competition for the hearts and minds of the developing world.

In his speech at Yale University during his recent visit to the US, President Hu Jintao (胡錦濤) set out -- for the first time in such a forum -- the Chinese view of a harmonious world based on the idea of Chinese civilization. The most dramatic changes, though -- albeit sotto voce -- have been taking place in east Asia.

Though far from Europe's line of vision -- it has had little stake in the region since the postwar collapse of the European empires there -- east Asia is pivotal to China's prospects and the future of Sino-US relations. For the last decade, China has been busy overhauling its approach to the region and involving itself for the first time in its multilateral arrangements. This process has been steadily accelerating, especially since the Asian financial crisis.

The key has been China's developing relationship with ASEAN, which comprises the nations of Southeast Asia and is by far the most important regional institution. China has made the running -- ahead of Japan -- in the creation of a nascent broader regional framework.

In Northeast Asia, it has used its role in the talks over North Korea to forge a much closer relationship with South Korea. All very reasonable. The result, however, has been the slow but steady marginalization of the US, a process exacerbated by the fact that US attention has been overwhelmingly directed towards the Middle East, which in the long run is actually far less important.

It is a combination of these developments that perhaps helps to explain why Hu Jintao's visit to the US was not accorded the full status of a visiting head of state. It was a deliberate snub, reflecting the unease with which Washington views the rise of China and its possible implications. But this was more a matter of pique than substance.

It is now too late for the administration of US President George W. Bush to seriously rethink its relationship with China, but this will surely be top of the agenda for the next administration. But it admits no easy solution. Whatever the Pentagon may suggest, the Chinese have been careful to avoid posing a military challenge to the US, which lay at the heart of the Cold War antagonism between the US and the Soviet Union.

Moreover, again unlike in the Cold War, the two countries now find themselves highly economically interdependent. Yet China's continuing rise is bound to provoke growing disquiet and anxiety in Washington. It is this relationship that will lie at the center of global politics; if that is not apparent at the moment, it will be very soon.

Martin Jacques is a visiting professor at Renmin University.

Concerns that the US might abandon Taiwan are often overstated. While US President Donald Trump’s handling of Ukraine raised unease in Taiwan, it is crucial to recognize that Taiwan is not Ukraine. Under Trump, the US views Ukraine largely as a European problem, whereas the Indo-Pacific region remains its primary geopolitical focus. Taipei holds immense strategic value for Washington and is unlikely to be treated as a bargaining chip in US-China relations. Trump’s vision of “making America great again” would be directly undermined by any move to abandon Taiwan. Despite the rhetoric of “America First,” the Trump administration understands the necessity of

In an article published on this page on Tuesday, Kaohsiung-based journalist Julien Oeuillet wrote that “legions of people worldwide would care if a disaster occurred in South Korea or Japan, but the same people would not bat an eyelid if Taiwan disappeared.” That is quite a statement. We are constantly reading about the importance of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC), hailed in Taiwan as the nation’s “silicon shield” protecting it from hostile foreign forces such as the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), and so crucial to the global supply chain for semiconductors that its loss would cost the global economy US$1

US President Donald Trump’s challenge to domestic American economic-political priorities, and abroad to the global balance of power, are not a threat to the security of Taiwan. Trump’s success can go far to contain the real threat — the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) surge to hegemony — while offering expanded defensive opportunities for Taiwan. In a stunning affirmation of the CCP policy of “forceful reunification,” an obscene euphemism for the invasion of Taiwan and the destruction of its democracy, on March 13, 2024, the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) used Chinese social media platforms to show the first-time linkage of three new

Sasha B. Chhabra’s column (“Michelle Yeoh should no longer be welcome,” March 26, page 8) lamented an Instagram post by renowned actress Michelle Yeoh (楊紫瓊) about her recent visit to “Taipei, China.” It is Chhabra’s opinion that, in response to parroting Beijing’s propaganda about the status of Taiwan, Yeoh should be banned from entering this nation and her films cut off from funding by government-backed agencies, as well as disqualified from competing in the Golden Horse Awards. She and other celebrities, he wrote, must be made to understand “that there are consequences for their actions if they become political pawns of