For the past five years I have been at war with the British action group Farmers for Action. These are the neanderthals who have held up the traffic and blockaded oil refineries in the UK in the hope of persuading the government to reduce the price of fuel. It doesn't matter how often you explain that cheap fuel, which allows the supermarkets to buy from wherever the price of meat or grain is lowest, has destroyed British farming. They will stand in front of the cameras and make us watch as they cut their own throats.

But through gritted teeth I must admit that they have got something right. In January the caveman in chief, David Handley, warned that foot and mouth disease had not been eliminated from Brazil, and that imports of meat from that country risked bringing it back to Britain. The buyers brushed his warning aside. In the first half of this year beef imports into the UK from Brazil to the UK rose by 70 percent, to 34,000 tonnes. Last week an outbreak was confirmed in the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso do Sul.

You would, of course, expect British producers to throw as much mud as they can at cheap imports. You would expect them to question their competitors' hygiene standards and social and environmental impacts, and Handley has done all of these things. And, to my intense annoyance, he is on every count correct.

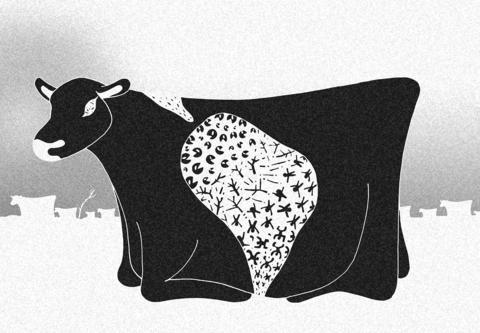

ILLUSTRATION: MOUNTAIN PEOPLE

Unlike him, I do not believe that British beef farmers have a God-given right to stay in business. We shouldn't be eating beef at all. Because the conversion efficiency of feed to meat is so low in cattle, there is no more wasteful kind of food production. British beef producers would be extinct were it not for subsidies and European tariffs. Brazilian meat threatens them only because it is so cheap that it can outcompete theirs even after trade taxes have been paid. But if it's unethical to eat British beef, it's 100 times worse to eat Brazilian.

Major exporter

Until 1990 Brazil produced only enough beef to feed itself. Since then its cattle herd has grown by some 50 million, and the country has become, according to some estimates, the world's biggest exporter: it now sells 1.9 million tonnes a year. After Russia, Egypt and Chile the UK is its fourth-largest customer. One region of Brazil is responsible for 80 percent of the growth in Brazilian beef production. It's the Amazon.

The past three years have been the most destructive in the Brazilian Amazon's history. Last year 26,000 km2 of rainforest were burned: the second-highest rate on record. This year could be worse.

And most of it is driven by cattle ranching.

According to the Center for International Forestry Research, cattle pasture accounts for six times more cleared land in the Amazon than crop land: even the notorious soya farmers, who have ploughed some 5 million hectares of former rainforest, cover just one-tenth of the ground taken by the beef producers. The four Amazon states in which the most beef is produced are the four with the highest deforestation rates.

Cattle ranching, if it keeps expanding in the Amazon, threatens two-fifths of the world's remaining rainforest. This is not just the most diverse ecosystem but also the biggest reserve of standing carbon. Its clearance could provoke a hydrological disaster in South America, as rainfall is reduced as the trees come down. Next time you see footage of the forest burning, remember that you might have paid for it.

Many Brazilians, especially those whose land is being grabbed by the cattlemen, are trying to stop the destruction. Ranchers have an effective argument: when people complain, they kill them. In February we heard an echo of the massacre which has so far claimed 1,200 lives, when the American nun Dorothy Stang was murdered -- almost certainly by beef producers. The ranchers believed to have killed her were, like cattlemen throughout the Amazon, protected by the police.

For the same reason, and despite the best efforts of President Lula, the ranchers are now employing some 25,000 slaves on their estates. These are people who are transported thousands of miles from their home states, then -- forced to buy their provisions from the ranch shop at inflated prices -- kept in permanent debt. Because of the expansion of beef production in the Amazon, slavery in Brazil has quintupled in 10 years.

So the government of a country which -- despite its best efforts -- has failed to stop slavery, murder and environmental catastrophe expects us to believe that its farm-hygiene standards are as rigorously enforced as those of any other nation. Anyone who has worked in the Amazon knows that there is no certificate which cannot be bought, and few local officials who aren't working for the people they are meant to regulate.

Foot and mouth

If foot and mouth disease is endemic in the Brazilian Amazon -- most of which is now registered by the government as "safe" -- the ministers in Brasilia will be the last to know.

When the disease last hit the UK, in February 2001, the government blamed it on meat imported by Chinese restaurants. But in April of that year we discovered that the farm on which the outbreak started, at Heddon-on-the-Wall in Northumberland, in the north east of England, had been taking slops for its pigs from the Whitburn army training camp near Sunderland, a few miles to the south.

The army had been importing some of its beef from Brazil and Uruguay, two of the strongholds of the type-O strain which infected British herds. The UK Ministry of Defence insisted that it came from "disease-free regions" of South America. One of them was Mato Grosso do Sul, the state in which foot and mouth has just erupted.

So who, in this country, has been buying it? UK supermarket giant Tesco says that "well over 90 percent" of its beef comes from the UK. It has stopped buying Brazilian since the outbreak last week, but can't tell me how much it bought before then, because that's "commercially sensitive."

I went round one of its stores and found that all the fresh beef was labelled "British" in big red letters. But six of its own-brand processed meals (generally the cheaper kinds) contained "South American beef," three contained "South American/EU beef" and one just "beef." Most of the ready meals supplied by other companies contained only "beef."

Fellow UK supermarket chain Sainsbury's admitted to buying 5 percent from Brazil until the disease was reported. The man from the Asda chain told me his chain bought "less than 2 percent" of its beef from Brazil this summer and nothing since. The main market, he claimed, is restaurants and pub chains.

I tried McDonald's and Burger King: they both say they don't buy from Brazil. So does the pub company Wetherspoons. Punch Taverns doesn't buy food, but its tenants are supplied by catering companies such as Brake Brothers. Brake Brothers admits to buying Brazilian beef, but the volume is, again, "competitively sensitive."

This doesn't necessarily mean that any of these firms have been buying beef from the Amazon: but buying beef from elsewhere in Brazil creates a hole in the domestic market, which will be filled by the growing production in the rainforest.

So, given that we're importing tens of thousands of tonnes a year, where has it gone? Where's the beef?

Unlike other meat, fresh beef's country of origin must in the UK -- because of bovine spongiform encephalopathy -- be printed on the packet. So, with a little detective work in shops and supermarkets and round the back of pubs, schools, hospitals and barracks, it shouldn't be too hard to trace.

Once you've found it, I suggest you back away.

Concerns that the US might abandon Taiwan are often overstated. While US President Donald Trump’s handling of Ukraine raised unease in Taiwan, it is crucial to recognize that Taiwan is not Ukraine. Under Trump, the US views Ukraine largely as a European problem, whereas the Indo-Pacific region remains its primary geopolitical focus. Taipei holds immense strategic value for Washington and is unlikely to be treated as a bargaining chip in US-China relations. Trump’s vision of “making America great again” would be directly undermined by any move to abandon Taiwan. Despite the rhetoric of “America First,” the Trump administration understands the necessity of

US President Donald Trump’s challenge to domestic American economic-political priorities, and abroad to the global balance of power, are not a threat to the security of Taiwan. Trump’s success can go far to contain the real threat — the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) surge to hegemony — while offering expanded defensive opportunities for Taiwan. In a stunning affirmation of the CCP policy of “forceful reunification,” an obscene euphemism for the invasion of Taiwan and the destruction of its democracy, on March 13, 2024, the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) used Chinese social media platforms to show the first-time linkage of three new

The military is conducting its annual Han Kuang exercises in phases. The minister of national defense recently said that this year’s scenarios would simulate defending the nation against possible actions the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) might take in an invasion of Taiwan, making the threat of a speculated Chinese invasion in 2027 a heated agenda item again. That year, also referred to as the “Davidson window,” is named after then-US Indo-Pacific Command Admiral Philip Davidson, who in 2021 warned that Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) had instructed the PLA to be ready to invade Taiwan by 2027. Xi in 2017

Sasha B. Chhabra’s column (“Michelle Yeoh should no longer be welcome,” March 26, page 8) lamented an Instagram post by renowned actress Michelle Yeoh (楊紫瓊) about her recent visit to “Taipei, China.” It is Chhabra’s opinion that, in response to parroting Beijing’s propaganda about the status of Taiwan, Yeoh should be banned from entering this nation and her films cut off from funding by government-backed agencies, as well as disqualified from competing in the Golden Horse Awards. She and other celebrities, he wrote, must be made to understand “that there are consequences for their actions if they become political pawns of