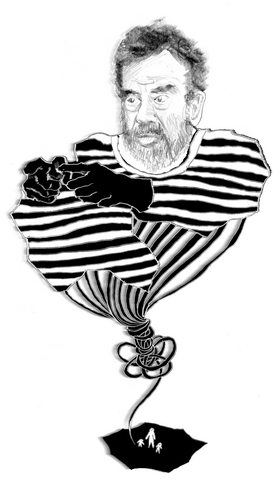

What is at stake in the trial of former Iraqi president Saddam Hussein, which began yesterday? Coming just four days after the referendum on Iraq's constitution and touted as a "constitutional moment" akin to the trials of Kings Charles X and Louis XVI, the proceedings are supposed to help advance Iraq's transition from tyranny to democracy. Will they?

So far, all signs suggest that the trial is unlikely to meet its ambitious aims. From the outset in postwar Iraq, criminal justice resembled deracinated constitutionalism: atomistic trials, radical purges and compromised elections. Most egregious was the post-invasion rush to "de-Baathification," which eviscerated many of the country's existing institutions.

The mix of individual and collective responsibility associated with repressive regimes often creates a dilemma concerning how to deal with the old institutions. But, in Iraq, flushing out the military and the police merely left the country in a domestic security vacuum. By the time that mistake was recognized, the damage was done, needlessly sacrificing security. Moreover, potential sources of legitimacy in Iraq's ongoing constitutional reform, such as parliament, were also destroyed.

The lack of legitimate institutions needed to rebuild the rule of law is evident in the debate over what authority and whose judgment ought to be exercised over Saddam. Should the tribunal be national or international? This question highlights the problematic relationship of international humanitarian law to the use of force.

In the Balkans, the indictment of Slobodan Milosevic by the UN's International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) provided a boost to political change in the region. Regime delegitimation has become a leading function of the new permanent International Criminal Court.

But Iraq was different. Instead of recurring to an international forum, a devastating war was declared that went beyond deposing Saddam, wreaking damage on tens of thousands of civilians, and thus confounding the message of condemnation.

The origins of successor justice in the war means that the debate over its legitimacy overlaps with the broader schism over the intervention itself. So far, the UN, the EU and most human-rights groups have not cooperated with the Iraqi Special Tribunal (IST), owing to their opposition to the original military intervention, as well as the IST statute's authorization of the death penalty.

Ultimately, the debate over international versus national jurisdiction reflects a dichotomy that is no longer apt in contemporary political conditions, for it obscures the fact that international law is increasingly embedded within domestic law. Despite being putatively "national," the Iraq tribunal couches the relevant offenses in terms of "crimes against humanity."

But it is only now, after the war, that successor justice is being aimed at refining and consolidating the message of delegitimation and regime change. Despite its close links to the invasion, Saddam's trial is expected somehow to represent an independent Iraqi judgment, thereby constituting local accountability without exacerbating tensions and destabilizing the country further. Can it succeed?

From the start, the IST must constitute a robust symbol of Iraqi sovereignty. But its close association with the US-led invasion leaves it vulnerable to the charge of "victor's justice." Although officially adopted in December 2003 by the Iraqi Governing Council, the IST's statute was framed under contract to the US government and approved by Paul Bremer, the Coalition Provisional Authority's administrator. The US remains the driving force behind the IST, supplying the needed expertise.

For many Iraqis, it is hard to view the IST as anything other than an expression of the occupiers' will.

Indeed, the IST's close association with the establishment of a successor regime is fraught with political pitfalls. Transitional criminal justice must be broad enough to reconcile a divided Iraq, and, therefore, include Shiite and Kurdish crimes against humanity, while it apparently must also avoid embarrassing the US or its allies, particularly regarding their extensive dealings with Saddam's regime. But the appearance of selective or controlled justice will defeat the tribunal's purpose.

So will the specter of illiberal trial procedures -- another reason for the lack of international support for the IST. The original selection of judges by what was widely viewed as a wing of the occupation exposes the tribunal to allegations of bias and partiality, as have issues regarding access and transparency for defendants and others.

Moreover, the IST statute says nothing about the standard of proof, which means that guilt does not clearly have to be established beyond a reasonable doubt. While the first set of charges concerns the well-documented killings in Dujail and elsewhere in the 1980's, Milosevic's trial by the ICTY shows that it is far more difficult to establish "superior authority," linking the killings to the leader.

According to Iraqi President Jalal Talabani, this problem has ostensibly been "solved" by means of extracted confessions. Of course, if the IST's aim is to evoke the possibility of show trials rather than bolstering the rule of law, Talabani is quite right: problem solved. Criminal proceedings may then be downsized to a confession of a single massacre, as subsequent trials are shelved to open the way for punishment -- unlike, say, the Milosevic trial, which is now dragging into its fourth year.

But rapid punishment -- most likely execution -- threatens to bury the full record of decades of tyranny under the apparently overriding purpose of fighting the insurgency by other means.

Saddam's trial will thus demonstrate the limits of the law in jumpstarting regime transition. An intractable dilemma of transitional justice is that societies ravaged by brutal human rights legacies often appeal to the law to shore up the legitimacy of the successor regime, only to see these salutary aims subverted by the challenges and compromises that are inherent to the transition itself.

Ruti Teitel is a professor of comparative law at New York Law School. Copyright: Project Syndicate

Concerns that the US might abandon Taiwan are often overstated. While US President Donald Trump’s handling of Ukraine raised unease in Taiwan, it is crucial to recognize that Taiwan is not Ukraine. Under Trump, the US views Ukraine largely as a European problem, whereas the Indo-Pacific region remains its primary geopolitical focus. Taipei holds immense strategic value for Washington and is unlikely to be treated as a bargaining chip in US-China relations. Trump’s vision of “making America great again” would be directly undermined by any move to abandon Taiwan. Despite the rhetoric of “America First,” the Trump administration understands the necessity of

US President Donald Trump’s challenge to domestic American economic-political priorities, and abroad to the global balance of power, are not a threat to the security of Taiwan. Trump’s success can go far to contain the real threat — the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) surge to hegemony — while offering expanded defensive opportunities for Taiwan. In a stunning affirmation of the CCP policy of “forceful reunification,” an obscene euphemism for the invasion of Taiwan and the destruction of its democracy, on March 13, 2024, the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) used Chinese social media platforms to show the first-time linkage of three new

If you had a vision of the future where China did not dominate the global car industry, you can kiss those dreams goodbye. That is because US President Donald Trump’s promised 25 percent tariff on auto imports takes an ax to the only bits of the emerging electric vehicle (EV) supply chain that are not already dominated by Beijing. The biggest losers when the levies take effect this week would be Japan and South Korea. They account for one-third of the cars imported into the US, and as much as two-thirds of those imported from outside North America. (Mexico and Canada, while

I have heard people equate the government’s stance on resisting forced unification with China or the conditional reinstatement of the military court system with the rise of the Nazis before World War II. The comparison is absurd. There is no meaningful parallel between the government and Nazi Germany, nor does such a mindset exist within the general public in Taiwan. It is important to remember that the German public bore some responsibility for the horrors of the Holocaust. Post-World War II Germany’s transitional justice efforts were rooted in a national reckoning and introspection. Many Jews were sent to concentration camps not