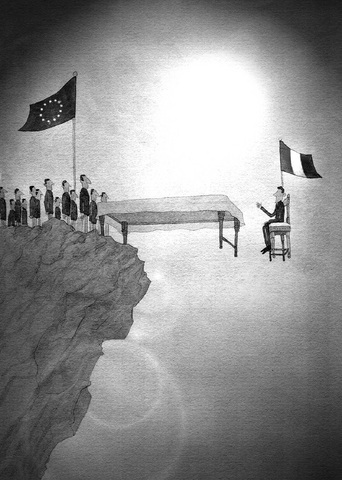

Voting "no" on the EU Constitution would not constitute a French "no" to Europe, as some believe; it would merely be a vote of no confidence in Jacques Chirac's presidency. Anything that diminishes Chirac -- who has weakened the EU by pushing a protectionist, corporate state model for Europe and telling the new smaller members to "shut up" when they disagreed with him -- must be considered good news for Europe and European integration.

So those desiring a stronger integrated EU should be rooting for a French "no," knowing full well that some voting "no" would be doing the right thing for the wrong reasons.

Even before this month's referendum, there have been indications that France's ability to mold the EU to its interests has been waning.

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

Just recently, Romanian President Traian Barescu signed the treaty to join the EU. In the period preceding the signing, however, French Foreign Minister Michel Barnier chastised him for lacking a "European reflex." The reason? Barescu plans to align Romania with Anglo-Saxon liberal economic policies, and wants a special relationship with Great Britain and the US to improve security in the Black Sea region. Rather than buckling to France's will, the Romanian president warned French leaders to stop lecturing his country.

This is Europe's future. Even those with close historical ties to France, like Romania, are standing up to France, because Chirac and his colleagues do not offer them the type of "European reflex" they want and need.

The Netherlands -- a traditionally pro-European country -- also may vote "no" on the Constitution in its own referendum (which takes place after the French one) -- not only as a protest against the conservative and moralistic policies of the Balkenende government, but as a rejection of a corporatist Europe dominated by French and German interests.

The corporate state simply has not delivered the goods in continental Europe, and polls are showing voters may take it out on the proposed Constitution.

Certainly the "yes" camp is concerned, with some arguing a French "no" will stall EU enlargement and sink the euro.

"What prospects would there be for constructive talks with Turkey, or progress towards entry of the Balkan states if the French electorate turned its back on the EU?" asks Philip Stephens in the Financial Times. True enough. But a "no" will not mean the French electorate has turned its back on Europe. What's at stake is not enlargement, but whether enlargement takes a more corporatist or market-based form.

Wolfgang Munchau of the Financial Times thinks French rejection of the EU Constitution could sink the euro.

"Without the prospect of eventual political union on the basis of some constitutional treaty," wrote Munchau, "a single currency was always difficult to justify and it might turn out more difficult to sustain ? Without the politics, the euro is "no"t nearly as attractive."

But French rejection of the Constitution does not imply political fragmentation of the EU. If the Constitution is not ratified, the Treaty of Nice becomes the union's operative document. There is no reason whatsoever why the EU should fall into chaos -- and the euro wilt -- now under the Treaty of Nice when it did not do so before.

The truth is that not only will the euro survive a "no" vote; it will prosper. Britain's liberal economic principles are more conducive to European economic growth and prosperity than France's protectionist, corporate-state ones. The market realizes this. With the polls forecasting a "no" vote, the euro remains strong in the currency markets.

Finally, not only will a French "no" serve to marginalize Chirac in Europe, but it will also help undermine the Franco-German alliance that has served France, Germany and Europe so badly in recent years. Europe, in fact, might be on the verge of a major political re-alignment if the French vote "no" and British Prime Minister Tony Blair wins big in the forthcoming UK election. With Chirac down and Blair up, an Anglo Saxon-German alliance might well replace the present Franco-German one. That would be progress indeed.

Melvyn Krauss is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University. Copyright: Project Syndicate

After more than three weeks since the Honduran elections took place, its National Electoral Council finally certified the new president of Honduras. During the campaign, the two leading contenders, Nasry Asfura and Salvador Nasralla, who according to the council were separated by 27,026 votes in the final tally, promised to restore diplomatic ties with Taiwan if elected. Nasralla refused to accept the result and said that he would challenge all the irregularities in court. However, with formal recognition from the US and rapid acknowledgment from key regional governments, including Argentina and Panama, a reversal of the results appears institutionally and politically

In 2009, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) made a welcome move to offer in-house contracts to all outsourced employees. It was a step forward for labor relations and the enterprise facing long-standing issues around outsourcing. TSMC founder Morris Chang (張忠謀) once said: “Anything that goes against basic values and principles must be reformed regardless of the cost — on this, there can be no compromise.” The quote is a testament to a core belief of the company’s culture: Injustices must be faced head-on and set right. If TSMC can be clear on its convictions, then should the Ministry of Education

The Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) provided several reasons for military drills it conducted in five zones around Taiwan on Monday and yesterday. The first was as a warning to “Taiwanese independence forces” to cease and desist. This is a consistent line from the Chinese authorities. The second was that the drills were aimed at “deterrence” of outside military intervention. Monday’s announcement of the drills was the first time that Beijing has publicly used the second reason for conducting such drills. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership is clearly rattled by “external forces” apparently consolidating around an intention to intervene. The targets of

China’s recent aggressive military posture around Taiwan simply reflects the truth that China is a millennium behind, as Kobe City Councilor Norihiro Uehata has commented. While democratic countries work for peace, prosperity and progress, authoritarian countries such as Russia and China only care about territorial expansion, superpower status and world dominance, while their people suffer. Two millennia ago, the ancient Chinese philosopher Mencius (孟子) would have advised Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) that “people are the most important, state is lesser, and the ruler is the least important.” In fact, the reverse order is causing the great depression in China right now,