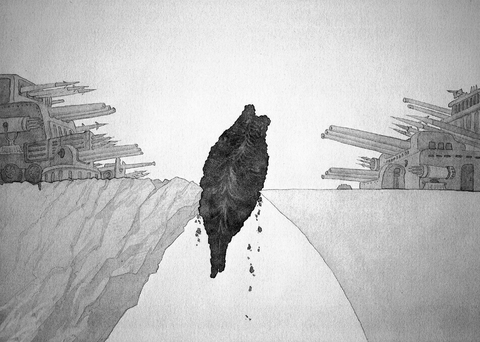

The National People's Congress has never been what you could call a radical body. So when it adopted the "Anti-Secession" Law, a measure that gives China the right -- in its own eyes at least -- to take military action against any attempt by Taiwan to declare formal independence, it is obvious to everyone that this is the voice of the Chinese party-state.

In Shanghai a few days after the measure was adopted, I asked China's foreign ministry spokesman what China could possibly gain by military action against Taiwan.

"It would," he said, "restore the territorial integrity so beloved of the Chinese people."

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

This is a saga that goes back to 1949, (Editor's note: The question of Taiwan's sovereignty has been in doubt in the modern era since at least 1874, after the Mutan Incident) when two political paths diverged: the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), led by Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石), retreated offshore to Taiwan after losing the civil war to Mao Zedong's (毛澤東) communist forces.

US support kept Taiwan, no doubt unreasonably, in the security council until, in the last twist of the Cold War narrative, President Richard Nixon played his China card. Taipei was dumped; Beijing became the new best friend (Editor's note: Nixon's trip to Beijing marked the thawing of diplomatic relations between the US and the People's Republic of China, however Beijing was not diplomatically recognized by the US until 1979, under then president Jimmy Carter).

Since then, it would be tempting to read in the twin tracks of Taiwan and the People's Republic of China the inevitable eclipse and eventual absorption of Taiwan by Beijing. China would certainly like to read history that way and, as its power expands, its impatience has grown. There is one China, says Beijing, and the world, its eye on China's growing power, or covetously on its booming market, nods in agreement. How to make the facts on the ground conform to the rhetorical position, though, is re-emerging on the international agenda in a worryingly dangerous fashion.

The military option would be so detrimental to China's real interests that it is hard to imagine that even in Beijing it is regarded as a serious option. More than 50 years have elapsed since Beijing's military occupation of Tibet, and it remains a troubled project. To force an occupation of Taiwan now would set in train a resistance a hundred times more powerful. Diplomatically isolated Taiwan may be, but that does not mean the world would be indifferent to its fate.

In the last few weeks the issue of Taiwan has been discussed almost exclusively in military terms: first a subtle shift in diplomatic language in Japan provoked an indignant response from Beijing. Now Taiwan has reacted furiously to Beijing's Anti-Secession Law, and Washington has been forced to express disapproval and reiterate US willingness to defend Taiwan.

At the same time, Washington has been putting heavy pressure on the EU to prevent it lifting the arms embargo to China imposed after the 1989 Tiananmen Massacre. Normally sober senators are talking excitedly about trade sanctions and are citing growing tensions over Taiwan in support of their censure of what they describe as an irresponsible European move.

There is a case against lifting the arms embargo, but it is more a moral than a military one, a question of signals rather than hardware. As far as hardware is concerned, US indignation might have been better spent on China's second most important supplier of lethal and hi-tech hardware, Israel. (Editor's note: The US has often prevented Israel from selling weapons to China or upgrading its weapons systems, as the author herself notes below).

Israel repays US military generosity by reverse-engineering US weaponry and selling it on. Among other items, Israel has sold China advanced fighter planes and Python 3 missiles. Only last December the US stepped in to prevent Israel from upgrading an unnamed "sensitive weapons system" sold to China in the 1990s. Should it ever come to blows, US forces will find themselves defending Taiwan against missiles sold to the Chinese by Israel.

Coming to blows, though, would be catastrophic for all concerned.

China's military war-games focus on Taiwan regularly: it is the most significant project of the People's Liberation Army, apart from the task of keeping the home front in order. They like to be ready for any move by Taiwan toward formal independence, however unlikely.

A senior Chinese official recently confided that Beijing was haunted by the thought that Taiwan planned to declare independence on the eve of the Beijing Olympics, on the assumption that Beijing would not wish to spoil the party with a war.

But all of this moves the issue in the wrong direction. The only way Beijing will achieve its stated objective of "reunification" with Taiwan is by becoming a country with which the Taiwanese people would wish to be "reunited."

After decades of dictatorship, Taiwan has become a functioning democracy. Why should its people want to give that up for arbitrary rule from Beijing? If Beijing really wants to advance the prospects of unification it should offer reassurance, rather than threats.

There is, indeed, one immediate step Beijing could take: to give Hong Kong a full franchise and allow the direct election of its next chief executive. Not only could Beijing gain brownie points, but it could demonstrate to Taiwan that "one country, two systems," was a formula that could be trusted.

If Beijing believes in peaceful unification, it is time it began to show it.

George Santayana wrote: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” This article will help readers avoid repeating mistakes by examining four examples from the civil war between the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) forces and the Republic of China (ROC) forces that involved two city sieges and two island invasions. The city sieges compared are Changchun (May to October 1948) and Beiping (November 1948 to January 1949, renamed Beijing after its capture), and attempts to invade Kinmen (October 1949) and Hainan (April 1950). Comparing and contrasting these examples, we can learn how Taiwan may prevent a war with

A recent trio of opinion articles in this newspaper reflects the growing anxiety surrounding Washington’s reported request for Taiwan to shift up to 50 percent of its semiconductor production abroad — a process likely to take 10 years, even under the most serious and coordinated effort. Simon H. Tang (湯先鈍) issued a sharp warning (“US trade threatens silicon shield,” Oct. 4, page 8), calling the move a threat to Taiwan’s “silicon shield,” which he argues deters aggression by making Taiwan indispensable. On the same day, Hsiao Hsi-huei (蕭錫惠) (“Responding to US semiconductor policy shift,” Oct. 4, page 8) focused on

Taiwan is rapidly accelerating toward becoming a “super-aged society” — moving at one of the fastest rates globally — with the proportion of elderly people in the population sharply rising. While the demographic shift of “fewer births than deaths” is no longer an anomaly, the nation’s legal framework and social customs appear stuck in the last century. Without adjustments, incidents like last month’s viral kicking incident on the Taipei MRT involving a 73-year-old woman would continue to proliferate, sowing seeds of generational distrust and conflict. The Senior Citizens Welfare Act (老人福利法), originally enacted in 1980 and revised multiple times, positions older

Nvidia Corp’s plan to build its new headquarters at the Beitou Shilin Science Park’s T17 and T18 plots has stalled over a land rights dispute, prompting the Taipei City Government to propose the T12 plot as an alternative. The city government has also increased pressure on Shin Kong Life Insurance Co, which holds the development rights for the T17 and T18 plots. The proposal is the latest by the city government over the past few months — and part of an ongoing negotiation strategy between the two sides. Whether Shin Kong Life Insurance backs down might be the key factor