Countries that are rich in natural resources are often poor, because exploiting those resources has taken precedence over good government. Competing oil and mining companies, backed by their governments, are often willing to deal with anyone who can assure them of a concession.

This has bred corrupt and repressive governments and armed conflict. In Africa, resource-rich countries like Congo, Angola and Sudan have been devastated by civil wars. In the Middle East, democratic development has been lagging.

Curing this "resource curse" could make a major contribution to alleviating poverty and misery in the world, and there is an international movement afoot to do just that. The first step is transparency; the second is accountability.

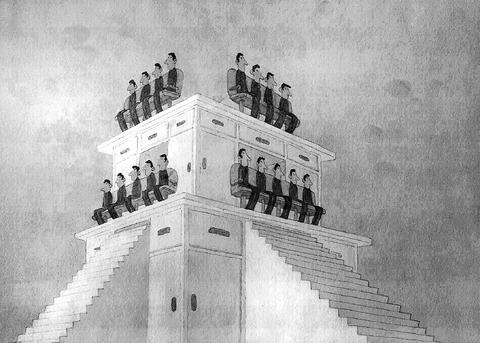

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

The movement started a few years ago with the Publish What You Pay campaign, which urged oil and mining companies to disclose payments to governments. In response, the British government launched the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). Three years into the process, the UK convened an important EITI conference in London attended by representatives of governments, business and civil society.

Much has already been accomplished. On the business side, the major international extractive companies have started to acknowledge the value and necessity of greater transparency. British Petroleum has undertaken to disclose disaggregated payment information on its operations in Azerbaijan, and Royal Dutch Shell is doing the same in Nigeria. ChevronTexaco recently negotiated an agreement with Nigeria and Sao Tome that includes a transparency clause requiring publication of company payments in the joint production zone.

Most encouraging is that producing countries themselves are beginning to seize the initiative. Nigeria is reorganizing its state oil company, introducing transparency legislation, and launching sweeping audits of the oil and gas sector. It plans to begin publishing details of company payments to the state this summer.

The Kyrgyz Republic became the first country to report under EITI, for a large gold-mining project. Azerbaijan will report oil revenues later this month. Ghana and Trinidad and Tobago have also signed on. Peru, Sao Tome and Principe, and East Timor are currently in negotiations to implement the initiative.

Equally important, local activists in many of these countries are starting to use EITI as an opening to demand greater public accountability for government spending. My own foundation, the Open Society Institute, has established Revenue Watch programs in producing countries such as Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Mongolia and Iraq.

But there is a lot more to be done. Two-thirds of the world's most impoverished people live in about 60 developing or transition countries that depend on oil, mining or gas revenues. The recently published transparency index from Save the Children UK shows that transparency is the exception, not the rule. Many important producing countries have yet to make even a gesture toward disclosure. There is no reason the major Middle Eastern producers should not be part of this transparency push, and Indonesia should join its neighbor East Timor in embracing the EITI. It is also critical that state-owned companies, which account for the bulk of global oil and gas production, be subject to full disclosure.

Other governments need to follow the UK's lead and become involved politically and financially in expanding the EITI. France appears to have done little to encourage countries within its sphere of influence, much less to ensure that its own companies begin disclosing. The Bush administration's recent decision to initiate a parallel anti-corruption process through the G8 leaves the US outside the premier international forum for addressing transparency in resource revenues while unnecessarily reinventing the wheel in the process.

Nor have the US and UK used their power in Iraq to promote transparency in the oil sector. Let us hope that the new Iraqi government does better. It is difficult to see how democracy can take root if the country's most important source of income remains as veiled in secrecy as it was under former Iraqi president Saddam Hussein.

The EITI still has a long way to go, but it is one of the most effective vehicles available for achieving a global standard of disclosure and accountability. This week's summit is an opportunity to assess progress and to define more precisely what it means to implement the EITI by establishing some basic minimum requirements on host countries.

Those committed to seeing the wealth generated by energy and mining finally result in better lives for ordinary people would do well to invest in the initiative during this critical stage. The EITI may not be a catchy acronym, but in concert with civil society efforts such as Publish What You Pay, it promises to do a lot more good in the world than most.

George Soros is president of Soros Fund Management and chairman of the Open Society Institute.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

There are moments in history when America has turned its back on its principles and withdrawn from past commitments in service of higher goals. For example, US-Soviet Cold War competition compelled America to make a range of deals with unsavory and undemocratic figures across Latin America and Africa in service of geostrategic aims. The United States overlooked mass atrocities against the Bengali population in modern-day Bangladesh in the early 1970s in service of its tilt toward Pakistan, a relationship the Nixon administration deemed critical to its larger aims in developing relations with China. Then, of course, America switched diplomatic recognition

The international women’s soccer match between Taiwan and New Zealand at the Kaohsiung Nanzih Football Stadium, scheduled for Tuesday last week, was canceled at the last minute amid safety concerns over poor field conditions raised by the visiting team. The Football Ferns, as New Zealand’s women’s soccer team are known, had arrived in Taiwan one week earlier to prepare and soon raised their concerns. Efforts were made to improve the field, but the replacement patches of grass could not grow fast enough. The Football Ferns canceled the closed-door training match and then days later, the main event against Team Taiwan. The safety

The National Immigration Agency on Tuesday said it had notified some naturalized citizens from China that they still had to renounce their People’s Republic of China (PRC) citizenship. They must provide proof that they have canceled their household registration in China within three months of the receipt of the notice. If they do not, the agency said it would cancel their household registration in Taiwan. Chinese are required to give up their PRC citizenship and household registration to become Republic of China (ROC) nationals, Mainland Affairs Council Minister Chiu Chui-cheng (邱垂正) said. He was referring to Article 9-1 of the Act

The Chinese government on March 29 sent shock waves through the Tibetan Buddhist community by announcing the untimely death of one of its most revered spiritual figures, Hungkar Dorje Rinpoche. His sudden passing in Vietnam raised widespread suspicion and concern among his followers, who demanded an investigation. International human rights organization Human Rights Watch joined their call and urged a thorough investigation into his death, highlighting the potential involvement of the Chinese government. At just 56 years old, Rinpoche was influential not only as a spiritual leader, but also for his steadfast efforts to preserve and promote Tibetan identity and cultural