The unveiled faces of Saudi women will be open to public scrutiny from next year under a government order making it mandatory for women to carry their own, separate photographic identity card.

As of the middle of next year, it will be compulsory for every Saudi woman to have her own ID card, terminating the practice of the current family card, an identity pass that does not carry a photo of the woman and lists her as a dependent of her father or husband.

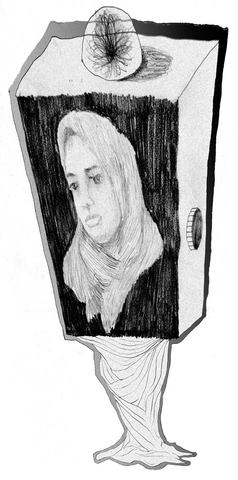

While it may seem a small move, the ID card is a big step in Saudi society where women are hidden behind veils, under-represented and deprived of most of the rights males enjoy in the country. Women's faces remain unseen in public, even in the media.

ILLUSTRATION: MOUNTAIN PEOPLE

Conservatives in the Islamic kingdom have objected to the proposal since it was first raised by the Saudi government in 1999.

Islamic hard-liners object on the grounds that photographing the female face is un-Islamic, and likened to pimps men who would allow their female family members to have their photographs stuck on ID cards.

Such a comparison does not come as a surprise in a country were women are not allowed to drive, travel without written permission of a male guardian, or vote in the landmark municipal elections underway in the kingdom.

Saudi Arabia's traditional society is segregated and in public women wear long black robes called an abaya, plus a veil covering their heads and sometimes their faces.

Women are only encouraged to enter professions in fields where they are unlikely to have contact with men, such as education.

If they are business owners, they must appoint a male "agent" to take care of government transactions.

Hissah Al-Suwaileh, head of the Women's Civil Status Department in Riyadh, was quoted by the Arab News as saying that Saudi women required photographic ID cards to prove their identity and stamp out fraud.

The cards, to be issued by al-Suwaileh's department, would in future be the only card recognized by banks and government sectors.

"It is a necessity that must be acknowledged," said a Saudi female employee at one of the local banks who identified herself only as Noura.

"We've been asking clients to bring in their passports and those who don't have them, they've got to bring in a male guardian to verify their identities. After all, the family card only has her name on it which in any day and age could never be enough," Noura said.

"The process of identification has kept pace with modern technology in many parts of the world with voice detectors, retina and palm scanners being used. We however are still at point zero dealing with the photo issue: To show or not to show," she said.

Al-Suwaileh voiced concern that many Saudi women are misinformed about the requirements for applying for an ID card. They assume that the approval of their male guardians is a fundamental condition to obtain one.

This is not accurate, she says. A Saudi woman who has a valid passport can apply and obtain her ID card without the consent of a male guardian. Only when a woman does not hold her own passport does she need a male guardian to verify her identity.

But this new regulation has a drawback. Saudi women need the permission of a male guardian to obtain a passport in the first place.

"A Saudi woman can only obtain a passport with the consent of her male guardian, so what's a national ID card in comparison to the license to travel?" one applicant asked.

After more than three weeks since the Honduran elections took place, its National Electoral Council finally certified the new president of Honduras. During the campaign, the two leading contenders, Nasry Asfura and Salvador Nasralla, who according to the council were separated by 27,026 votes in the final tally, promised to restore diplomatic ties with Taiwan if elected. Nasralla refused to accept the result and said that he would challenge all the irregularities in court. However, with formal recognition from the US and rapid acknowledgment from key regional governments, including Argentina and Panama, a reversal of the results appears institutionally and politically

In 2009, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) made a welcome move to offer in-house contracts to all outsourced employees. It was a step forward for labor relations and the enterprise facing long-standing issues around outsourcing. TSMC founder Morris Chang (張忠謀) once said: “Anything that goes against basic values and principles must be reformed regardless of the cost — on this, there can be no compromise.” The quote is a testament to a core belief of the company’s culture: Injustices must be faced head-on and set right. If TSMC can be clear on its convictions, then should the Ministry of Education

The Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) provided several reasons for military drills it conducted in five zones around Taiwan on Monday and yesterday. The first was as a warning to “Taiwanese independence forces” to cease and desist. This is a consistent line from the Chinese authorities. The second was that the drills were aimed at “deterrence” of outside military intervention. Monday’s announcement of the drills was the first time that Beijing has publicly used the second reason for conducting such drills. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership is clearly rattled by “external forces” apparently consolidating around an intention to intervene. The targets of

China’s recent aggressive military posture around Taiwan simply reflects the truth that China is a millennium behind, as Kobe City Councilor Norihiro Uehata has commented. While democratic countries work for peace, prosperity and progress, authoritarian countries such as Russia and China only care about territorial expansion, superpower status and world dominance, while their people suffer. Two millennia ago, the ancient Chinese philosopher Mencius (孟子) would have advised Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) that “people are the most important, state is lesser, and the ruler is the least important.” In fact, the reverse order is causing the great depression in China right now,