The old man shields his eyes against the fierce light of the Altiplano and considers the question. When he talks about his ancestors, does he mean the Incas? No, he replies in a sort of Spanish creole, he means his great-great-grandfather. And with his right hand he makes a rotating gesture up and forwards from his body. The Incas, he adds, came way earlier. And with the same hand he sweeps even further forward, towards the mountains on the horizon.

In the next video clip, the researcher asks a woman to explain the origins of her culture. She starts by describing her parents' generation, then her grandparents,' and so on, extending her arm further and further in front of her as she does so. Then she switches to talk about how the values of those earlier generations have been handed back to her (her hand gradually returns to her body from out front), and how she will in turn pass them on to her children (she thumbs over her shoulder).

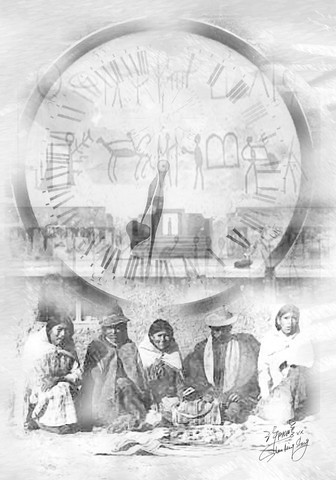

The man and woman belong to an Amerindian group called the Aymara, who inhabit some of the highest valleys in the Andes -- in their case, in northern Chile. The researcher is Rafael Nunez, a cognitive scientist at the University of California, San Diego, who is interested in how we develop abstract ideas like time. Nunez now believes that he has definitive evidence that the Aymara have a sense of the passage of time that is the mirror image of his own: the past is in front of them, the future behind.

With his collaborator, linguist Eve Sweetser, he will publish his findings later this year, but they have already prompted speculation as to whether other peoples might conceive of time like the Aymara. George Lakoff, a linguist at the University of California, Berkeley, thinks that it is a strong possibility. The clues lie in language, and as he points out, "There are 6,000 languages and most of them have never been written down." More fundamentally, Nunez and Sweetser's work highlights the illusory nature of time.

Time, as Einstein showed, is a tricky concept to nail down, and all languages resort to metaphor to express it. In fact, with staggering monotony, they all resort to the same metaphor: space. If an English speaker says: "We are approaching the deadline," he or she is expressing imminence in terms of nearness, a property of physical space. Anyone listening will understand exactly what he or she means, even though the deadline is not an entity that exists in the physical world. Nunez says: "There is no ultimate truth that you could discover that is outside that metaphor."

So if temporal landmarks don't exist except in our heads, where does our notion of time come from? And why do we feel so strongly a sense of time as motion? In all Indo-European languages including English, but also in languages as diverse as Hebrew, Polynesian, Japanese and Bantu, speakers face the future. Time flows from a point in front of them, through their current position -- the present -- and back to the past. The Aymara also feel time as motion, but for them, speakers face the past and have their backs to the future.

The Aymara word for past is transcribed as nayra, which literally means eye, sight or front. The word for future is q'ipa, which translates as behind or the back. The Jesuits undoubtedly noticed this oddity in the 16th century, when they ventured up into the mountains to spread the word. More recently, linguistic anthropologists have puzzled over what it means. In 1975, Andrew Miracle and Juan de Dios Yapita Moya, both at the University of Florida, observed that q'ipuru, the Aymara word for tomorrow, combines q'ipa and uru , the word for day, to produce a literal meaning of "some day behind one's back."

Over the years, rumors have surfaced of similar strangeness in other languages. Maori speakers use front-type words to signify events that happened earlier, Agathe Thornton, an expert in the Maori oral tradition reported in the 1980s. Malagasy, too, uses "in front of" to mean "earlier than." It began to look as if the Aymara weren't alone in spinning time's arrow -- until in 1980, Lakoff and Mark Johnson, a philosopher at the University of Oregon, warned against jumping to that conclusion.

Lakoff and Johnson realized that not only could different languages use different metaphors for time, but a single language could contain more than one metaphor. In English, for instance, speakers switch between at least two different frames of reference when discussing the order of events, a trick Nunez has demonstrated in a simple experiment. Ask any randomly selected group of English speakers to answer this question: if a meeting scheduled for Wednesday is moved forward two days, what day will it fall on?

"More or less 50 percent of the people will say Friday, and 50 percent will say Monday," Nunez says.

The word "moved" allows the ambiguity that the meeting is either being moved forward in time, meaning it will happen later, or being brought closer in time to the person. The reason for the split in answers is that half the people are using themselves as a reference. Time is moving towards them, so "forward" denotes into the future, hence Friday. But it is also possible to think in a temporal reference frame that excludes ego, as in, "Monday follows Sunday."

In that case, it is as if the speaker is looking out onto a landscape or conveyor belt of time from which he or she is removed. And on that conveyor belt, later events come after, or behind earlier ones. So moving the meeting forward means moving it to Monday.

A complex system of rules governs which metaphor is appropriate in a given context, but as Nunez's experiment demonstrates, some situations are ambiguous. He and colleague Ben Motz have even biased people's choice towards the Monday response by showing them in advance a sequence of cubes moving across a screen, a motion scene that does not depend on the observer's location.

So when it came to the Aymara, Nunez decided to proceed cautiously: "The question that has never been asked of Aymara is, when they use these two words, nayra and q'ipa, are they using them with reference to themselves, or to another time?" If to another time, they may not be doing anything very differently from his North American subjects who thought that the meeting would fall on a Monday; if to themselves, then he would have concrete evidence of a conceptual chasm that exists between them and us, the future gazers.

To find out which it was, he decided to study Aymara gesture and speech simultaneously, because in gesture people tend to act out the metaphor they are using in speech. Think of a person expressing a choice, who holds her palms upwards and alters their height as if weighing something on scales.

Braving the thin air at 4,000m, he interviewed 27 adults, some of whom spoke only Aymara, some of whom were bilingual in Aymara and Spanish -- chatting about old times and about future happenings in their community. In all, he collected about 20 hours of videotaped conversation, sections of which he later analyzed for synchronicity of word and gesture. And he found that the Aymara did indeed have two frames of reference when it came to time.

When they talked about very wide time spans, their gestures indicated that they conceived of it spanning from left to right, excluding themselves. But when they talked about shorter spans, several generations say, the axis was front-back, with them at point zero. The gestures of the old man and the woman discussing their grandparents confirmed that they really did think of the past as in front of them.

Nunez thinks that the reason the Aymara think they way they do might be connected with the importance they accord vision. Every language has a system of markers which forces the speaker to pay attention to some aspects of the information being conveyed and not others. French emphasizes the gender of an object (sa voiture, son livre), English the gender of the subject (his car, her book). Aymara marks whether the speaker saw the action happen or not: "Yesterday my mother cooked potatoes (but I did not see her do it)."

If these markers are left out, the speaker is regarded as boastful or a liar. Thirty years ago, Miracle and Yapita pointed to the often incredulous responses of Aymara to some written texts: "`Columbus discovered America' -- was the author actually there?" In a language so reliant on the eyewitness, it is not surprising that the speaker metaphorically faces what has already been seen: the past. It is even logical, says Lakoff.

"This Aymara finding is big news," says Vyvyan Evans, a theoretical cognitive linguist at the University of Sussex. "It is the first really well-documented example of the future and past being structured in a totally different way from lots of other languages, including English."

But Evans's own research had already predicted that there would be people in the world who view time differently. The only thing that all humans have in common when it comes to temporal experience is their brains' perceptual mechanisms. "There is change in our environment, there is motion in our environment, and we need to be able to deal with that information," says Evans. The human brain has therefore evolved to be able to recognize three basic components of time: duration, simultaneity and repetition.

Most languages have ways of expressing these three phenomena, but they might combine them into metaphors that are culturally determined. English, for instance, offers the possibility of buying time, while Aymara does not. The availability of different metaphors orients the whole language towards a subtly different, and perhaps unique, view of time. The closer the languages, the closer the metaphors. The Aymara have been pretty much isolated from the rest of the world for a long time, and for the moment, theirs is the only language in which a really dramatic divergence has been demonstrated. So it is hard to say to what extent their notion of time influences other areas of their thought -- or how English or Hebrew speakers' influences theirs. "It may not affect everything, but it may affect a lot of important things," says Lakoff. "For instance, you're probably not going to get the same metaphors for progress." In their 1975 paper, Miracle and Yapita described the "great patience" of the Aymara, who thought nothing of waiting half a day for a truck to take them to market. People from English-speaking cultures like to plan, and feel outraged when life intervenes.

But if you can't see the future, says Marta Hardman, an anthropologist at the University of Florida, there seems less point in planning. Hardman has studied the Aymara for 50 years -- Miracle and Yapita were her students. When she first arrived among the Aymara of Peru in the 1950s, she was struck by the absence of a sexual hierarchy. People made much of remembering where you came from. That might mean your community or your ancestors, or your mother. Women were respected more than in her home town.

"I was suddenly treated as a full person," she says. And 50 years on, she can't help feeling that it is her native culture, not the Aymara, which is going against the grain. In English we are encouraged to ignore the past, she says. "We pretend it's not there, yet we're lugging it with us as we go."

Concerns that the US might abandon Taiwan are often overstated. While US President Donald Trump’s handling of Ukraine raised unease in Taiwan, it is crucial to recognize that Taiwan is not Ukraine. Under Trump, the US views Ukraine largely as a European problem, whereas the Indo-Pacific region remains its primary geopolitical focus. Taipei holds immense strategic value for Washington and is unlikely to be treated as a bargaining chip in US-China relations. Trump’s vision of “making America great again” would be directly undermined by any move to abandon Taiwan. Despite the rhetoric of “America First,” the Trump administration understands the necessity of

US President Donald Trump’s challenge to domestic American economic-political priorities, and abroad to the global balance of power, are not a threat to the security of Taiwan. Trump’s success can go far to contain the real threat — the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) surge to hegemony — while offering expanded defensive opportunities for Taiwan. In a stunning affirmation of the CCP policy of “forceful reunification,” an obscene euphemism for the invasion of Taiwan and the destruction of its democracy, on March 13, 2024, the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) used Chinese social media platforms to show the first-time linkage of three new

If you had a vision of the future where China did not dominate the global car industry, you can kiss those dreams goodbye. That is because US President Donald Trump’s promised 25 percent tariff on auto imports takes an ax to the only bits of the emerging electric vehicle (EV) supply chain that are not already dominated by Beijing. The biggest losers when the levies take effect this week would be Japan and South Korea. They account for one-third of the cars imported into the US, and as much as two-thirds of those imported from outside North America. (Mexico and Canada, while

The military is conducting its annual Han Kuang exercises in phases. The minister of national defense recently said that this year’s scenarios would simulate defending the nation against possible actions the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) might take in an invasion of Taiwan, making the threat of a speculated Chinese invasion in 2027 a heated agenda item again. That year, also referred to as the “Davidson window,” is named after then-US Indo-Pacific Command Admiral Philip Davidson, who in 2021 warned that Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) had instructed the PLA to be ready to invade Taiwan by 2027. Xi in 2017