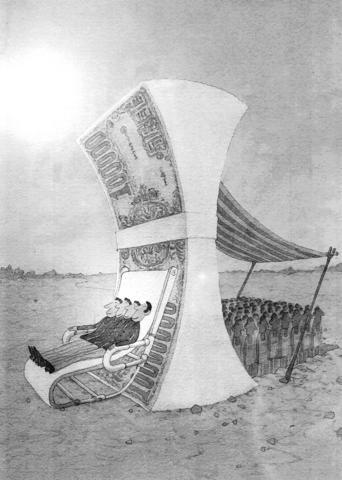

Labor disputes in southern China's booming Guangdong Province are becoming increasingly prominent as an unprecedented army of 30 million migrant workers clamors for better conditions and treatment.

This astonishing influx of cheap labor has been the engine of China's capitalist miracle, officials say, making Guangdong the nation's most prosperous region.

ILLUSTRATION: YUSHA

It has also turned the Pearl River Delta into an export-oriented manufacturing hub, from Hong Kong in the east to Foshan in the west.

But as the government tries to maintain the image of an investor's paradise based on low production costs, the workers, increasingly backed by state media, labor rights groups and even the courts, are clamoring for an end to slave-like working conditions.

"There are several causes of worker disputes, but the leading reason is when enterprises don't pay salaries," said Wang Guanyu, director of the Guangdong Labor and Employment Service and Administrative Center. "The workers are very aware of their need to protect themselves so if there are violations, they will complain directly about it."

Another cause is the sweatshop conditions at many factories, including low pay, seven-day work weeks, 15-hour working days, mandatory overtime, a poor working environment and often coercive factory regulations.

Recent riots at the Taiwanese-invested Stella International shoe factory in Dongguan and a spate of other smaller workers' strikes and walkouts in the region reflect the growing sense of labor strife.

"There is not a factory in Dongguan that abides by the Labor Law. I would say 50 to 60 percent of the factories here make you work seven days a week," said a worker surnamed Wu who toils at the city's Henghui packaging factory.

The Labor Law mandates a 40-hour, five-day work week and a range of worker benefits.

Rush of Migrants

Wang said the government's hands were too full trying to administer the migrant rush into Guangdong -- with numbers jumping from 5 million registered workers in 1995 to 10 million in 2001 and nearly 20 million last year -- to concentrate solely on labor issues.

Only registered workers who have had jobs for at least six months are included in the figures, with another 10 million unregistered workers also estimated to have met the six-month working criteria.

A further 10 million could be looking for work, Wang said.

This gives Guangdong by far the largest share of China's officially estimated 140 million migrant workers. Another around 6 million are in Shanghai and 5 million in Beijing.

Most of the workers in Guangdong are under 35, more than half are women and they largely come from impoverished inland provinces like Hunan, Hubei, Jiangxi, Anhui, Guangxi and Guizhou.

Many are engaged in light industrial manufacturing, including electronics, as well as cheap Chinese textiles like plastics, shoes, clothes, toys and furniture that are mainstays in markets worldwide.

`Market Forces'

The government's priority is creating more jobs by attracting investment and building more factories, and the implementation of legally mandated labor rights and benefits should be brought about with "market forces," Wang said.

"Generally speaking, we want to raise the quality and effectiveness of our labor force and this will mean higher wages and better benefits, but this is a process that will take time," Wang said.

"Right now we are hoping to allow the market to work for itself. If factories want a stable work force and don't want to see their trained workers leaving for other factories, then they are going to have to pay them better and give them better benefits."

Besides, it is nearly impossible to monitor work conditions at the tens of thousands of factories that have mushroomed in the region over the past 20 years, he said, admitting that labor laws and regulations were hard to enforce.

Reports last month by China's only legal trade union, the government-run All China Federation of Trade Unions, and the Communist Party-administered Jiusan research group showed migrants made up 35 percent of Guangdong's work force and were responsible for 25 percent of its GDP last year.

However, in the past 12 years their salaries have only risen 68 yuan (US$8) on average, said the reports, cited by the Yangcheng Evening News.

Salaries

Three-quarters of migrant workers in Guangdong made less than 1,000 yuan a month, with most of the rest earning less. Average monthly costs totalled 500 yuan.

By comparison, the average monthly salary for a non-migrant worker in Guangdong was 1,675 yuan.

Despite regulations that call on factories to give all workers retirement insurance, only half of migrant workers had any, the reports said.

Such conditions have resulted in large numbers of migrant workers frequently changing jobs.

Wang insisted that while conditions were difficult, "there are a lot of benefits too."

"Migrant workers in Guangdong made some 30 billion yuan last year, that is about an average of 8,000 yuan a year per worker. Much of that money goes back to their poor rural hometowns," he said.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion