The People's Bank of China and the Bank of Japan -- as well as other central banks in Asia -- are in trouble. They have accumulated vast foreign exchange reserves, estimated at more than US$2 trillion. The problem is that almost all of it is in US dollars -- a currency that is rapidly losing its value.

All policy options for Asia's central banks appear equally unattractive. If they do nothing and simply hold onto the dollars, their losses will only increase. But if they buy more, in an attempt to prop up the dollar, they will only have a bigger version of the same problem. If, on the contrary, they try to diversify into other currencies, they will drive down the dollar faster and create greater losses. They are also likely to encounter the same sort of problem with other possible reserve currencies.

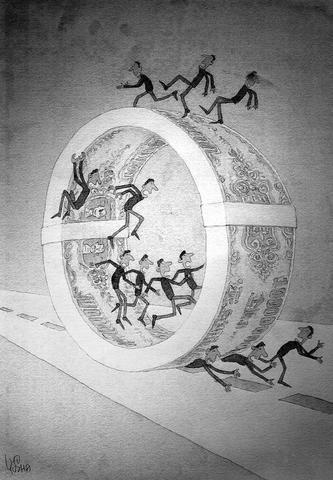

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

The euro has been touted as the replacement for or alternative to the dollar. Some enthusiastic Europeans encouraged Asians to diversify their reserve holdings. But the same scenario might well be repeated with the euro in a few years. Large fiscal deficits and slow growth might convince foreign exchange markets that there is little future in the euro, fueling a wave of selling -- and hence losses for central bank holders.

There is a historical parallel to today's concern about the world's major reserve currency. The interwar economy, shattered by the Great Depression of the early 1930s, offers a whole series of painful, but important, lessons for the present.

In the 1920s, the world economy was reconstructed around a fixed exchange rate regime in which many countries held their reserves not in gold (as was the practice before World War II) but in foreign exchange, especially in British sterling. During the course of the 1920s, some of the official holders of pounds grew nervous about Britain's weak foreign trade performance, which suggested that, like today's dollar, the currency was over-valued and would inevitably decline.

Foreign central banks asked whether the Bank of England was contemplating changing its view of the pound's exchange rate. Of course they were told that there was no intention of abandoning Britain's link to gold, and that the strong pound represented a deep and long commitment (in the same way that US Treasury Secretary John Snow today affirms the idea of a "strong dollar"). Only France ignored British statements and substantially sold off its sterling holdings.

When the inevitable British devaluation came on Sept. 20-21, 1931, many foreign central banks were badly hit and were blamed for mismanaging their reserves. Many were stripped of their responsibilities, and the persons involved were discredited. The Dutch central banker Gerard Vissering resigned and eventually killed himself as a result of the destruction wrought on his institution's balance sheet by the pound's collapse.

Some countries that traded a great deal with Britain, or were in the orbit of British imperial rule, continued to hold reserves in pounds after 1931. During World War II, Britain took advantage of this, and Argentina, Egypt, and India, in particular, built up huge claims on sterling, although it was an unattractive currency. At the war's end, they thought of a new way of using their reserves: spend them.

Consequently, these reserves provided the fuel for economic populism. Large holders of sterling balances -- India, Egypt and Argentina -- all embarked on major nationalizations and a public sector spending spree: they built railways, dams, steel works. The sterling balances proved to be the starting point of vast and inefficient state planning regimes that did long-term harm to growth prospects in all the countries that took this course.

Could something similar be in store for today's holders of large reserves? The most explicit call for the use of dollar reserves to finance a major program of infrastructure modernization has come from India, which has a similar problem to the one facing China and Japan. It will be similarly tempting elsewhere.

This temptation needs to be removed before the tempted yield to it. Reserve holdings represent an outdated concept, and the world should contemplate some way of making them less central to the operation of the international financial system.

To be sure, reserves are important to smooth out imbalances in a fixed exchange rate regime. But the world has moved since the 1970s in the direction of greater exchange rate flexibility.

Reserves are also clearly important for countries that produce only a few goods -- especially commodity producers -- and thus face big and unpredictable swings in world market prices. Dependency on coffee or cocoa exports requires a build-up of precautionary reserves. But this does not apply to China, Japan, or India, whose exports are diversified.

Today's big surplus countries do not need large reserves. They should reduce their holdings as quickly as possible, before they do something really stupid with the accumulated treasure.

Harold James is professor of history at Princeton University and author of The End of Globalization: Lessons from the Great Depression.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

There is much evidence that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is sending soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to support Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — and is learning lessons for a future war against Taiwan. Until now, the CCP has claimed that they have not sent PLA personnel to support Russian aggression. On 18 April, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelinskiy announced that the CCP is supplying war supplies such as gunpowder, artillery, and weapons subcomponents to Russia. When Zelinskiy announced on 9 April that the Ukrainian Army had captured two Chinese nationals fighting with Russians on the front line with details

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), joined by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), held a protest on Saturday on Ketagalan Boulevard in Taipei. They were essentially standing for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which is anxious about the mass recall campaign against KMT legislators. President William Lai (賴清德) said that if the opposition parties truly wanted to fight dictatorship, they should do so in Tiananmen Square — and at the very least, refrain from groveling to Chinese officials during their visits to China, alluding to meetings between KMT members and Chinese authorities. Now that China has been defined as a foreign hostile force,

On April 19, former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) gave a public speech, his first in about 17 years. During the address at the Ketagalan Institute in Taipei, Chen’s words were vague and his tone was sour. He said that democracy should not be used as an echo chamber for a single politician, that people must be tolerant of other views, that the president should not act as a dictator and that the judiciary should not get involved in politics. He then went on to say that others with different opinions should not be criticized as “XX fellow travelers,” in reference to

Within Taiwan’s education system exists a long-standing and deep-rooted culture of falsification. In the past month, a large number of “ghost signatures” — signatures using the names of deceased people — appeared on recall petitions submitted by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) against Democratic Progressive Party legislators Rosalia Wu (吳思瑤) and Wu Pei-yi (吳沛憶). An investigation revealed a high degree of overlap between the deceased signatories and the KMT’s membership roster. It also showed that documents had been forged. However, that culture of cheating and fabrication did not just appear out of thin air — it is linked to the