They walk the walk. They talk the talk. But they don't think the think. In the wake of the huge support given to US President George W. Bush two weeks ago, it's time we realized how different America's majority culture is, and changed our policies accordingly.

What Americans share with Europeans are not values, but institutions. The distinction is crucial. Like us, they have a separation of powers between executive and legislature, an independent judiciary, and the rule of law. But the American majority's social and moral values differ enormously from those which guide most Europeans.

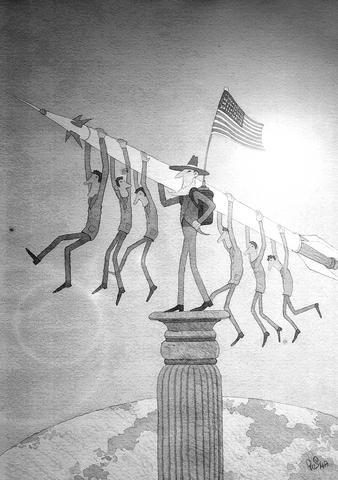

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

Its dangerous ignorance of the world, a mixture of intellectual isolationism and imperial intervention abroad, is equally alien. In the US more people have guns than have passports. Is there one European nation of which the same is true?

Of course, millions of US citizens do share "European" values. But to believe that this minority amounts to 48 percent and that America is deeply polarized is incorrect. It encourages the illusion that things may improve when Bush is gone. In fact, most voters for Senator John Kerry are as conservative as the Bush majority on the issues which worry Europeans. Kerry never came out for US even-handedness on the Israel- Palestine conflict, or for a withdrawal from Iraq.

Many commentators now argue for Europe to distance itself. But vague pleas for greater European coherence or for British Prime Minister Tony Blair to end his close links with the White House are not enough. The call should not be for "more" independence. Europe needs full independence.

We must go all the way, up to the termination of NATO. An alliance which should have wound up when the Soviet Union collapsed now serves almost entirely as a device for giving the US an unfair and unreciprocated droit de regard over European foreign policy.

As long as we are officially embedded as America's allies, the default option is that we have to support America and respect its "leadership." This makes it harder for European governments to break ranks, for fear of being attacked as disloyal. The default option should be that we, like they, have our interests. Sometimes they will coincide. Sometimes they will differ. But that is normal.

In other parts of the world, a handful of countries have bilateral defense treaties with the US. Some in Europe might want the same if NATO didn't exist. In contrast, a few members of the EU who chose to take the considerable risk of staying neutral during the cold war -- such as Austria, Finland, Ireland and Sweden -- see no need to join NATO in the much safer world we live in today.

So it makes no sense that the largest and most powerful European states, those who are most able to defend themselves, should cling to outdated anxiety and the notion that their ultimate security depends on the US. Do we really need American nuclear weapons to protect us against terrorists or so-called rogue states? The last time Europe was in dire straits, as Nazi tanks swept across the continent in 1939 and 1940, the US stayed on the sidelines until Pearl Harbor.

There is a school of thought which says that NATO is virtually defunct, so there is no need to worry about it. That view is sometimes heard even in Russia, where the so-called "realists" argue that Russia cannot oppose its old enemy, in spite of Washington's undisguised efforts to encircle it with bases in the Caucasus and central Asia. The more Moscow tries, they say, the more it seems to justify US claims that Russia is expansionist -- however odd that sounds, coming from a far more expansionist Washington.

It is true that NATO is unlikely ever again to function with the unanimity it showed during the cold war. The lesson from Iraq is that the alliance has become no more than a "coalition of the reluctant," with key members like France and Germany opting out of joint action.

But it is wrong to be complacent about NATO's alleged impotence or irrelevance. NATO gives the US a significant instrument for moral and political pressure. Europe is automatically expected to tag along in going to war, or in the post-conflict phase, as in Afghanistan or Iraq. Who knows whether Iran and Syria will come next? Bush has four more years in power and there is little likelihood that his successors in the White House will be any less interventionist.

NATO, in short, has become a threat to Europe. Its existence also acts as a continual drag on Europe's efforts to build its own security institutions. Certain member countries, particularly Britain, constantly look over their shoulders for fear of upsetting big brother. This has an inhibiting effect on every initiative.

France's more robust stance is pilloried by the Atlanticists as nostalgia for unilateral grandeur instead of being seen as part of France's pro-European search for a security project that will help us all.

Paradoxically, one argument for voting no in the referendum on the European constitution is based on this. Paul Quiles, a French socialist former defense minister, points out that Britain forced a change in the constitution's text so that Europe's common security policy, even as it tries to gather strength, is required to give primacy to NATO. Without control over its own defense, he argues, greater European integration makes little sense.

The immediate priority on the road to European independence is to abandon support for Bush's disastrous Iraq policy and get behind the majority of Iraqis who want the US to stop attacking their cities and leave the country. They feel US forces only provoke more insecurity and death.

Since Bush's victory two NATO members, Hungary and the Netherlands (which has a rightwing government), have said they will pull their troops out in March next year. Their moves show the falsity of the "old Europe, new Europe" split. In the post-communist countries, as much as in western Europe, majorities consistently opposed Bush's Iraq adventure, whatever their more timid governments said. Wanting to withdraw support for US foreign policy is not a left or right issue.

Ending NATO would not mean that Europe rejects good relations with the US. Nor does it rule out police and intelligence collaboration on issues of concern, such as the way to protect our countries against terrorism. Europe could still join the US in war, if there was an international consensus and the electorates of individual countries supported it.

But Europeans must reach their decisions from a position of genuine independence. The US has always based its approach to Europe on a calculation of interest rather than from sentimental motives.

Europe should do no less. We can and, for the most part, should be America's friends. Allies, no longer.

Concerns that the US might abandon Taiwan are often overstated. While US President Donald Trump’s handling of Ukraine raised unease in Taiwan, it is crucial to recognize that Taiwan is not Ukraine. Under Trump, the US views Ukraine largely as a European problem, whereas the Indo-Pacific region remains its primary geopolitical focus. Taipei holds immense strategic value for Washington and is unlikely to be treated as a bargaining chip in US-China relations. Trump’s vision of “making America great again” would be directly undermined by any move to abandon Taiwan. Despite the rhetoric of “America First,” the Trump administration understands the necessity of

US President Donald Trump’s challenge to domestic American economic-political priorities, and abroad to the global balance of power, are not a threat to the security of Taiwan. Trump’s success can go far to contain the real threat — the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) surge to hegemony — while offering expanded defensive opportunities for Taiwan. In a stunning affirmation of the CCP policy of “forceful reunification,” an obscene euphemism for the invasion of Taiwan and the destruction of its democracy, on March 13, 2024, the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) used Chinese social media platforms to show the first-time linkage of three new

If you had a vision of the future where China did not dominate the global car industry, you can kiss those dreams goodbye. That is because US President Donald Trump’s promised 25 percent tariff on auto imports takes an ax to the only bits of the emerging electric vehicle (EV) supply chain that are not already dominated by Beijing. The biggest losers when the levies take effect this week would be Japan and South Korea. They account for one-third of the cars imported into the US, and as much as two-thirds of those imported from outside North America. (Mexico and Canada, while

The military is conducting its annual Han Kuang exercises in phases. The minister of national defense recently said that this year’s scenarios would simulate defending the nation against possible actions the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) might take in an invasion of Taiwan, making the threat of a speculated Chinese invasion in 2027 a heated agenda item again. That year, also referred to as the “Davidson window,” is named after then-US Indo-Pacific Command Admiral Philip Davidson, who in 2021 warned that Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) had instructed the PLA to be ready to invade Taiwan by 2027. Xi in 2017