Asia has been gripped by election fever all year. The Philippines and Taiwan have chosen new presidents; India and Malaysia have ushered in new parliaments and prime ministers. This month brings two more vital polls: a legislative election in Hong Kong and a presidential election in Indonesia.

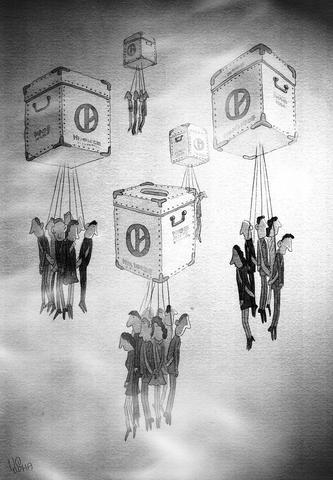

Voters there may also extend a disturbing paradox that has emerged in the region: the more "vigorous" Asian democracy becomes, the more dysfunctional it is.

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

There is no shortage of examples. The attempt by opposition parties to impeach South Korean President Roh Moo-hyun on the flimsiest of excuses; Taiwan President Chen Shui-bian's (陳水扁) inability to pass legislation through a legislature controlled by the opposition Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT); Philippine President Gloria Arroyo's stalemated first term and the logjam over the fiscal reforms needed to prevent a predicted Argentine-style meltdown: each bears testimony to democratic paralysis.

If deadlock and confusion were the only results, such political impasses might be tolerable. But chronic stalemate has confronted many Asian democracies with the threat of being discredited, a potential for violence and the prospect of economic decline.

Indeed, the precedents of democratic immobility in Asia are hardly encouraging. For example, since Pakistan's creation in 1947, partisan divisions have ensured that no elected government has been able to serve its full term. So Pakistanis have grimly accepted military rule as their destiny.

The problem in Asia often arises from something the French call "cohabitation," an awkward arrangement by which a directly elected president must co-exist with a legislature controlled by a rival party or parties.

The US and Europe's mature democracies may function well enough with the "checks and balances" of divided government (though the Republicans' bid to impeach former US president Bill Clinton might suggest otherwise), but in Asia the failure to bestow executive and legislative powers on a single institution is usually a terrible drawback.

This seems especially true when a government tries to enact radical economic or political reforms. The elected president wants to act, but the assembly refuses to approve the necessary laws. Or vice versa.

The pattern begins in parliamentary deadlock. Incompetent leaders blame legislatures for their failures; legislators blame presidents from rival parties. Finger-pointing replaces responsibility, fueling popular demand for a strongman (or woman) who can override political divisions. Indira Gandhi's "emergency rule" in the 1970s was partly the result of such institutional dysfunction.

Divided government also plays into the hands of Asia's separatists. At a critical moment for Sri Lanka's peace process, President Chandrika Kumaratunga was so incensed by the policies of her political rival that she sacked three of his ministers and called elections almost four years early. The only people who seem to have benefited from this democratic division are the murderous Tamil Tigers. Similarly, in Nepal, a Maoist insurgency has taken advantage of divisions between the king and legislature to gain control of much of the countryside.

However unstable, Asian democracies are preferable to autocracies, whether military, as in Pakistan and Burma, or communist, as in China and Vietnam. But the danger in a weakened democracy is not merely blocked legislation and ineffective government.

Ambitious but thwarted presidents are easily tempted to take unconstitutional measures; after all, they reason, the people elected them directly. The same is true of some prime ministers, like Thailand's authoritarian Thaksin Shinawatra, who now stands accused of weakening his country's democratic traditions in favor of personal rule.

Given these precedents and the widespread instability exposed by this year's elections, perhaps Asian policymakers should consider the merits of doing away with "cohabitation" and adopting systems where electoral victory translates into real power. Of course, parliamentary political systems are far from perfect. Neither Singapore nor Malaysia, where ruling parties have long dominated the parliaments, has a political culture as healthy as that of Taiwan or South Korea.

But in parliamentary democracies such as Japan and India, an elected leader runs the country until the day his or her party or coalition loses its legislative majority. This means that governments are judged not by their ability to outmaneuver legislatures, but by the quality of their policies. This seems to be a more efficient -- and politically more stable -- form of democracy than the unhappy cohabitation that produces such ugly confrontations in Taiwan, South Korea and the Philippines.

By contrast, the threats posed by divided government could be greater than mere parliamentary rumbles. Cohabitation could very soon become a problem even in Hong Kong, if on Sept. 12 voters elect a legislature hostile to Chief Executive Tung Chee-hwa (董建華). Indonesia also risks deadlock if, as seems likely, the election on Sept. 20 produces a president from a different party than the one that controls parliament.

Abraham Lincoln was right: a house divided against itself cannot stand. In many Asian democracies, only institutional reconstruction will prevent a collapse.

Satyabrata Rai Chowdhuri is an emeritus professor at India's University Grants Commission and former professor of international relations at Oxford University.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

Two weeks ago, Malaysian actress Michelle Yeoh (楊紫瓊) raised hackles in Taiwan by posting to her 2.6 million Instagram followers that she was visiting “Taipei, China.” Yeoh’s post continues a long-standing trend of Chinese propaganda that spreads disinformation about Taiwan’s political status and geography, aimed at deceiving the world into supporting its illegitimate claims to Taiwan, which is not and has never been part of China. Taiwan must respond to this blatant act of cognitive warfare. Failure to respond merely cedes ground to China to continue its efforts to conquer Taiwan in the global consciousness to justify an invasion. Taiwan’s government

This month’s news that Taiwan ranks as Asia’s happiest place according to this year’s World Happiness Report deserves both celebration and reflection. Moving up from 31st to 27th globally and surpassing Singapore as Asia’s happiness leader is gratifying, but the true significance lies deeper than these statistics. As a society at the crossroads of Eastern tradition and Western influence, Taiwan embodies a distinctive approach to happiness worth examining more closely. The report highlights Taiwan’s exceptional habit of sharing meals — 10.1 shared meals out of 14 weekly opportunities, ranking eighth globally. This practice is not merely about food, but represents something more

In an article published on this page on Tuesday, Kaohsiung-based journalist Julien Oeuillet wrote that “legions of people worldwide would care if a disaster occurred in South Korea or Japan, but the same people would not bat an eyelid if Taiwan disappeared.” That is quite a statement. We are constantly reading about the importance of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC), hailed in Taiwan as the nation’s “silicon shield” protecting it from hostile foreign forces such as the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), and so crucial to the global supply chain for semiconductors that its loss would cost the global economy US$1

Concerns that the US might abandon Taiwan are often overstated. While US President Donald Trump’s handling of Ukraine raised unease in Taiwan, it is crucial to recognize that Taiwan is not Ukraine. Under Trump, the US views Ukraine largely as a European problem, whereas the Indo-Pacific region remains its primary geopolitical focus. Taipei holds immense strategic value for Washington and is unlikely to be treated as a bargaining chip in US-China relations. Trump’s vision of “making America great again” would be directly undermined by any move to abandon Taiwan. Despite the rhetoric of “America First,” the Trump administration understands the necessity of