When Human Rights Watch declared last January that the Iraq War did not qualify as a humanitarian intervention, the international media took notice. According to the Internet database Factiva, 43 news articles mentioned the report, in publications ranging from the Kansas City Star to the Beirut Daily Star. Similarly, after the abuses of Iraqi detainees at the Abu Ghraib prison were disclosed, the views of Amnesty International and the International Committee of the Red Cross put pressure on the Bush administration both at home and abroad.

As these examples suggest, today's information age has been marked by the growing role of non-governmental organizations (NGO's) on the international stage. This is not entirely new, but modern communications have led to a dramatic increase in scale, with the number of NGO's jumping from 6,000 to approximately 26,000 during the 1990's alone. Nor do numbers tell the whole story, because they represent only formally constituted organizations.

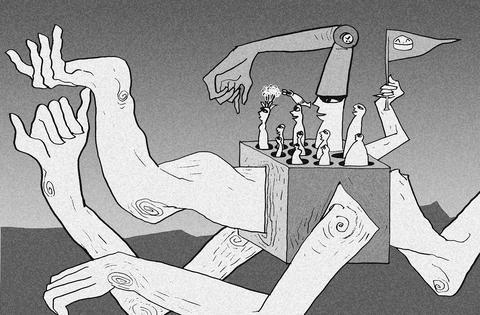

Many NGOs claim to act as a "global conscience," representing broad public interests beyond the purview of individual states. They develop new norms by directly pressing governments and businesses to change policies, and indirectly by altering public perceptions of what governments and firms should do. NGOs do not have coercive "hard" power, but they often enjoy considerable "soft" power -- the ability to get the outcomes they want through attraction rather than compulsion. Because they attract followers, governments must take them into account both as allies and adversaries.

ILLUSTRATION MOUNTAIN PEOPLE

A few decades ago, large organizations like multinational corporations or the Roman Catholic Church were the most typical type of transnational organization. Such organizations remain important, but the reduced cost of communication in the Internet era has opened the field to loosely structured network organizations with little headquarters staff and even to individuals. These flexible groups are particularly effective in penetrating states without regard to borders. Because they often involve citizens who are well placed in the domestic politics of several countries, they can focus the attention of media and governments onto their issues, creating new transnational political coalitions.

A rough way to gauge the increasing importance of transnational organizations is to count how many times these organizations are mentioned in mainstream media publications. The use of the term "non-governmental organization" or "NGO" has increased 17-fold since 1992. In addition to Human Rights Watch, other NGO's such as Transparency International, Oxfam, and Doctors without Borders have undergone exponential growth in terms of mainstream media mentions. By this measure, the biggest NGOs have become established players in the battle for the attention of influential editors.

In these circumstances, governments can no longer maintain the barriers to information flows that historically protected officials from outside scrutiny. Even large countries with hard power, such as the US, are affected. NGOs played key roles in the disruption of the WTO summit in 1999, the passage of the Landmines Treaty, and the ratification of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in May last year.

The US, for example, initially had strong objections to the Convention on Tobacco Control, but dropped them in the face of international criticism. The Landmines Treaty was created despite the opposition of the strongest bureaucracy (the Pentagon) in the world's largest military power.

Similarly, transnational corporations are often targets of NGO campaigns to "name and shame" companies that pay low wages in poor countries. Such campaigns sometimes succeed because they can credibly threaten to damage the value of global brand names.

Royal Dutch Shell, for example, announced last year that it would not drill in any spots designated by UNESCO as World Heritage sites. This decision came two years after the company acceded to pressure from environmentalists and scrapped plans to drill in a World Heritage site in Bangladesh. Transnational drug companies were shamed by NGOs into abandoning lawsuits in South Africa in 2002 over infringements of their patents on drugs to fight AIDS. Similar campaigns of naming and shaming have affected the investment and employment patterns of Mattel, Nike, and a host of other companies.

NGOs vary enormously in their organization, budgets, accountability, and sense of responsibility for the accuracy of their claims. It is hyperbole when activists call such movements "the world's other superpower," yet governments ignore them at their peril.

Some have reputations and credibility that give them impressive domestic as well as international soft power. Others lack credibility among moderate citizens but can mobilize demonstrations that demand the attention of governments. For better and for worse, NGOs and network organizations have resources and do not hesitate to use them.

Do NGOs make world politics more democratic? Not in the traditional sense of the word. Most are elite organizations with narrow membership bases. Some act irresponsibly and with little accountability. Yet they tend to pluralize world politics by calling attention to issues that governments prefer to ignore, and by acting as pressure groups across borders. In that sense, they serve as antidotes to traditional government bureaucracies.

Governments remain the major actors in world politics, but they now must share the stage with many more competitors for attention. Non-governmental actors are changing world politics. After Abu Ghraib, even US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld must take notice.

Joseph Nye is dean of Harvard's Kennedy School of Government and author of Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. Copyright: Project Syndicate

I came to Taiwan to pursue my degree thinking that Taiwanese are “friendly,” but I was welcomed by Taiwanese classmates laughing at my friend’s name, Maria (瑪莉亞). At the time, I could not understand why they were mocking the name of Jesus’ mother. Later, I learned that “Maria” had become a stereotype — a shorthand for Filipino migrant workers. That was because many Filipino women in Taiwan, especially those who became house helpers, happen to have that name. With the rapidly increasing number of foreigners coming to Taiwan to work or study, more Taiwanese are interacting, socializing and forming relationships with

Two weeks ago, Malaysian actress Michelle Yeoh (楊紫瓊) raised hackles in Taiwan by posting to her 2.6 million Instagram followers that she was visiting “Taipei, China.” Yeoh’s post continues a long-standing trend of Chinese propaganda that spreads disinformation about Taiwan’s political status and geography, aimed at deceiving the world into supporting its illegitimate claims to Taiwan, which is not and has never been part of China. Taiwan must respond to this blatant act of cognitive warfare. Failure to respond merely cedes ground to China to continue its efforts to conquer Taiwan in the global consciousness to justify an invasion. Taiwan’s government

Earlier signs suggest that US President Donald Trump’s policy on Taiwan is set to move in a more resolute direction, as his administration begins to take a tougher approach toward America’s main challenger at the global level, China. Despite its deepening economic woes, China continues to flex its muscles, including conducting provocative military drills off Taiwan, Australia and Vietnam recently. A recent Trump-signed memorandum on America’s investment policy was more about the China threat than about anything else. Singling out the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as a foreign adversary directing investments in American companies to obtain cutting-edge technologies, it said

The recent termination of Tibetan-language broadcasts by Voice of America (VOA) and Radio Free Asia (RFA) is a significant setback for Tibetans both in Tibet and across the global diaspora. The broadcasts have long served as a vital lifeline, providing uncensored news, cultural preservation and a sense of connection for a community often isolated by geopolitical realities. For Tibetans living under Chinese rule, access to independent information is severely restricted. The Chinese government tightly controls media and censors content that challenges its narrative. VOA and RFA broadcasts have been among the few sources of uncensored news available to Tibetans, offering insights