The latest buzzword in the globalization debate is outsourcing. Suddenly Americans -- long champions of globalization -- seem concerned about its adverse effects on their economy. Its ardent defenders are, of course, untroubled by the loss of jobs. They stress that outsourcing cuts costs -- just like a technological change that improves productivity, thus increasing profits -- and what is good for profits must be good for the American economy.

The laws of economics, they assert, ensure that in the long run there will be jobs for everyone who wants them, so long as government does not interfere in market processes by setting minimum wages or ensuring job security, or so long as unions don't drive up wages excessively. In competitive markets, the law of demand and supply ensures that eventually, in the long run, the demand for labor will equal the supply -- there will be no unemployment. But as Keynes put it so poignantly, in the long run, we are all dead.

Those who summarily dismiss the loss of jobs miss a key point: the US' economy has not been performing well. In addition to the trade and budget deficits, there is a jobs deficit. Over the past three and a half years, the economy should have created some 4 million to 6 million jobs to provide employment for new entrants into the labor force. In fact, more than 2 million jobs have been destroyed -- the first time since Herbert Hoover's presidency at the beginning of the Great Depression that there has been a net job loss in the US economy over the term of an entire presidential administration.

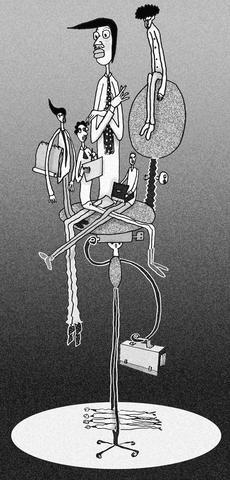

ILLUSTRATION MOUNTAIN PEOPLE

At the very least, this shows that markets by themselves do not quickly work to ensure that there is a job for everyone who wishes to work. There is an important role for government in ensuring full employment -- a role that the administration of US President George W. Bush has badly mismanaged. Were unemployment lower, the worries about outsourcing would be less.

But there is, I think, an even deeper reason for concerns about outsourcing of, say, high-tech jobs to India: It destroys the myth -- which has been a central tenet of the globalization debate in the US and other advanced industrial countries -- that workers should not be afraid of globalization.

Yes, apologists of outsourcing say, rich countries will lose low-skilled jobs in areas like textiles to low-wage labor in China and elsewhere. But this is supposedly a good thing, not a bad thing, because the US should be specializing in its areas of comparative advantage, involving skilled labor and advanced technology. What is required is "upskilling," improving the quality of education, especially in science and technology.

But this argument no longer seems convincing. The US is producing fewer engineers than China and India, and, even if engineers from those developing countries are at some disadvantage, either because of training or location, that disadvantage is more than offset by wage differentials. American and rich country engineers and computer specialists will either have to accept a wage cut and/or they will be forced into unemployment and/or to seek other employment -- almost surely at lower wages.?

If the US' highly trained engineers and computer specialists are unable to withstand the onslaught of outsourcing, what about those who are even less trained? Yes, the US may be able to maintain a competitive advantage at the very top, the breakthrough research, the invention of the next laser. But a majority of even highly trained engineers and scientists are involved in what is called "ordinary science," the important, day-to-day improvements in technology that are the basis of long-term increases in productivity -- and it is not clear that the US has a long-term competitive advantage here.

Two lessons emerge from the outsourcing debate. First, as the US grapples with the challenges of adjusting to globalization, it should be more sensitive to the plight of developing countries, which have far fewer resources to cope. After all, if the US, with its relatively low level of unemployment and social safety net, finds it must take action to protect its workers and firms against competition from abroad -- whether in software or steel -- such action by developing countries is all the more justified.

Second, the time for the US to worry is now. Many of globalization's advocates continue to claim that the number of jobs outsourced is relatively small. There is controversy, of course, about the eventual size, with some claiming that as many as one job in two might eventually be outsourced, others contending that the potential is much more limited. Haircuts, like a host of other activities requiring detailed local knowledge, cannot be outsourced.

But even if the eventual numbers are limited, there can be dramatic effects on workers and the distribution of income. Growth will be enhanced, but workers may be worse off -- and not just those who lose their jobs. This has, indeed, already happened in some developed countries: In the 10 years that have passed since the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement, average real wages in the US have actually declined.

Putting one's head in the sand and pretending that everyone will benefit from globalization is foolish. The problem with globalization today is precisely that a few may benefit and a majority may be worse off, unless government takes an active role in managing and shaping it. This is the most important lesson of the ongoing debate over outsourcing.

Joseph Stiglitz is professor of economics at Columbia University and a member of the Commission on the Social Dimensions of Globalization. He received the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2001.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

Concerns that the US might abandon Taiwan are often overstated. While US President Donald Trump’s handling of Ukraine raised unease in Taiwan, it is crucial to recognize that Taiwan is not Ukraine. Under Trump, the US views Ukraine largely as a European problem, whereas the Indo-Pacific region remains its primary geopolitical focus. Taipei holds immense strategic value for Washington and is unlikely to be treated as a bargaining chip in US-China relations. Trump’s vision of “making America great again” would be directly undermined by any move to abandon Taiwan. Despite the rhetoric of “America First,” the Trump administration understands the necessity of

US President Donald Trump’s challenge to domestic American economic-political priorities, and abroad to the global balance of power, are not a threat to the security of Taiwan. Trump’s success can go far to contain the real threat — the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) surge to hegemony — while offering expanded defensive opportunities for Taiwan. In a stunning affirmation of the CCP policy of “forceful reunification,” an obscene euphemism for the invasion of Taiwan and the destruction of its democracy, on March 13, 2024, the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) used Chinese social media platforms to show the first-time linkage of three new

The military is conducting its annual Han Kuang exercises in phases. The minister of national defense recently said that this year’s scenarios would simulate defending the nation against possible actions the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) might take in an invasion of Taiwan, making the threat of a speculated Chinese invasion in 2027 a heated agenda item again. That year, also referred to as the “Davidson window,” is named after then-US Indo-Pacific Command Admiral Philip Davidson, who in 2021 warned that Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) had instructed the PLA to be ready to invade Taiwan by 2027. Xi in 2017

If you had a vision of the future where China did not dominate the global car industry, you can kiss those dreams goodbye. That is because US President Donald Trump’s promised 25 percent tariff on auto imports takes an ax to the only bits of the emerging electric vehicle (EV) supply chain that are not already dominated by Beijing. The biggest losers when the levies take effect this week would be Japan and South Korea. They account for one-third of the cars imported into the US, and as much as two-thirds of those imported from outside North America. (Mexico and Canada, while