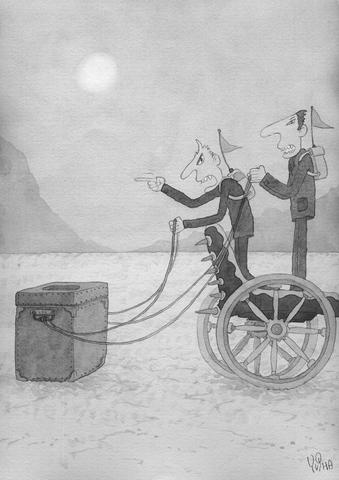

Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon's proposal for a unilateral Israeli withdrawal from the Gaza Strip and part

of the West Bank has been overwhelmingly defeated by a referendum within his own party, Likud, in what seems to be a humiliating defeat. Yet this is likely to have little or no effect on Sharon's intention to carry out the plan.

At first, this seems surprising, since he said before the referendum that he would abide by its outcome. But Sharon is 75 years old and probably within two years of retirement. He is determined that his plan become his political legacy. Since there is no precedent for a party referendum, he can argue that the vote does not bind him.

Moreover, Sharon made sure that his main political rivals -- notably former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu -- supported his plan. They are now in no position to challenge him as the champions of the opposition within Likud.

So while some members may walk out, Sharon can easily hold on to control of the party. In addition, many Sharon supporters, torn by what they saw as the plan's combination of costs and benefits, stayed home or even voted against it, but still want Sharon as their leader.

But Sharon is prepared to go even further in taking political risks to push through the withdrawal. Small right-wing parties in his coalition have already announced that his determination to do so will make them walk out of the government. Sharon will then turn to the leader of the opposition, 80-year-old former prime minister Shimon Peres, to form a national unity government. And Peres is ready to do so.

The passionate debate stirred up by Sharon's plan shows how truly revolutionary his proposal is. Having the army uproot Jewish settlements -- with inevitable scenes of settlers resisting and being dragged off -- will be a traumatic event for the country. The plan also entails considerable strategic risks, which, probably more than the prospect of uprooted settlements, account for the large "no" vote by Likud members.

A key concern is the precedent of withdrawal from southern Lebanon in 2000. Today, most Israelis believe that this step, though justified on strategic grounds in the face of constant attacks by the Lebanese group Hezbollah, convinced Palestinians that violence worked. In the same manner, a withdrawal from Gaza, many people worry, will bring increased anarchy there and a rise in overall terrorist attacks.

But convinced -- as are most Israelis -- that there is no Palestinian partner ready to negotiate seriously and implement its promises, the prime minister wants to prepare for an extended interim period. Assuming that terrorist attacks against Israel are going to continue under any circumstances, he seeks to improve the country's strategic position to handle this war.

Combined with the Gaza Strip's long-completed security fence and one being built near Israel's border with the West Bank, pulling out of the most exposed positions is intended to reduce casualties and the number of clashes with the Palestinians. A secondary intention is to show the world that Israel is ready to withdraw from most of the remaining territories it captured in 1967 in exchange for real peace.

The US and Britain have supported the withdrawal plan, while most other European countries have been critical. While demanding an Israeli withdrawal for years, the Palestinian leadership opposes Sharon's plan, arguing it is intended to create permanent borders. Nevertheless, if implemented, Sharon's proposal would leave Palestinians in control of about 99 percent of the Gaza Strip and roughly 50 percent of the West Bank.

If it appears that the withdrawal will proceed and Sharon can assemble a government to implement it, the Palestinian side will then face a major challenge. Will it be able to put together an effective governmental authority to rule the Gaza Strip, or will that area dissolve into bloody battles among Palestinian factions and

a staging area for attacks into Israel that will bring reprisal raids?

A key issue in this mix is the division of power between the nationalist Fatah group and the Islamist Hamas organization. Local Fatah officials want support from Palestinian President Yasser Arafat, to take firm control of the territory. But Arafat has shown a willingness to let groups act as they please, apparently believing that continuing unrest will bring international sympathy and intervention on his behalf.

Yet Arafat himself will be 75 in a few months and is clearly reaching the end of his career. He has been the only leader his movement has ever known, having led Fatah for 40 years and the Palestinians

as a whole for 35 years. With no apparent successor, his departure from the scene will bring a massive and unpredictable shake-up in Palestinian politics.

The Israeli government's projection has been that both the withdrawal and the security fence will be completed by the end of next year. Sharon's retirement is likely to come within another 12 months, with a new opposition leader having to be chosen as well.

Thus, while the Likud referendum seems to have left the Israeli-Palestinian dispute at yet another impasse, both sides

are on the verge of enormous changes.

Barry Rubin is director of the Global Research in International Affairs Center, editor of the Middle East Review of International Affairs and co-author of Yasser Arafat: A Political Biography. Copyright: Project Syndicate

Concerns that the US might abandon Taiwan are often overstated. While US President Donald Trump’s handling of Ukraine raised unease in Taiwan, it is crucial to recognize that Taiwan is not Ukraine. Under Trump, the US views Ukraine largely as a European problem, whereas the Indo-Pacific region remains its primary geopolitical focus. Taipei holds immense strategic value for Washington and is unlikely to be treated as a bargaining chip in US-China relations. Trump’s vision of “making America great again” would be directly undermined by any move to abandon Taiwan. Despite the rhetoric of “America First,” the Trump administration understands the necessity of

US President Donald Trump’s challenge to domestic American economic-political priorities, and abroad to the global balance of power, are not a threat to the security of Taiwan. Trump’s success can go far to contain the real threat — the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) surge to hegemony — while offering expanded defensive opportunities for Taiwan. In a stunning affirmation of the CCP policy of “forceful reunification,” an obscene euphemism for the invasion of Taiwan and the destruction of its democracy, on March 13, 2024, the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) used Chinese social media platforms to show the first-time linkage of three new

The military is conducting its annual Han Kuang exercises in phases. The minister of national defense recently said that this year’s scenarios would simulate defending the nation against possible actions the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) might take in an invasion of Taiwan, making the threat of a speculated Chinese invasion in 2027 a heated agenda item again. That year, also referred to as the “Davidson window,” is named after then-US Indo-Pacific Command Admiral Philip Davidson, who in 2021 warned that Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) had instructed the PLA to be ready to invade Taiwan by 2027. Xi in 2017

Sasha B. Chhabra’s column (“Michelle Yeoh should no longer be welcome,” March 26, page 8) lamented an Instagram post by renowned actress Michelle Yeoh (楊紫瓊) about her recent visit to “Taipei, China.” It is Chhabra’s opinion that, in response to parroting Beijing’s propaganda about the status of Taiwan, Yeoh should be banned from entering this nation and her films cut off from funding by government-backed agencies, as well as disqualified from competing in the Golden Horse Awards. She and other celebrities, he wrote, must be made to understand “that there are consequences for their actions if they become political pawns of