Last year, at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, George Carey, the former archbishop of Canterbury, asked US Secretary of State Colin Powell why the US seemed to focus only on its hard power rather than its soft power. Powell replied that the US had used hard power to win World War II, but he continued: "What followed immediately after hard power? Did the US ask for dominion over a single nation in Europe? No. Soft power came in the Marshall Plan. We did the same thing in Japan."

After the war in Iraq ended, I spoke about soft power (a concept I developed) to a conference co-sponsored by the US Army in Washington. One speaker was US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. According to a press account, "the top military brass listened sympathetically," but when someone asked Rumsfeld for his opinion on soft power, he replied, "I don't know what it means."

One of Rumsfeld's "rules" is that "weakness is provocative." He is correct, up to a point. As al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden observed, people like a strong horse. But power, defined as the ability to influence others, comes in many guises, and soft power is not weakness. On the contrary, it is the failure to use soft power effectively that weakens the US in the struggle against terrorism.

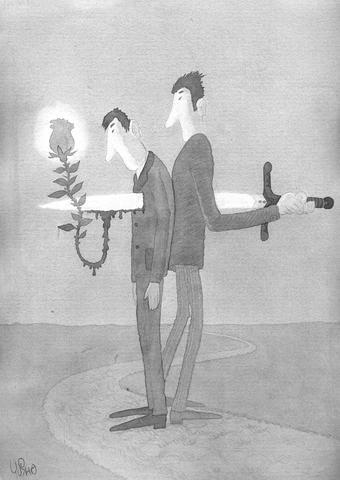

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

Soft power is the ability to get what one wants by attracting others rather than threatening or paying them. It is based on culture, political ideals and policies. When you persuade others to want what you want, you do not have to spend as much on sticks and carrots to move them in your direction.

A dazzling display

Hard power, which relies on coercion, grows out of military and economic might. It remains crucial in a world populated by threatening states and terrorist organizations.

But soft power will become increasingly critical in preventing terrorists from gaining supporters and for gaining the international cooperation necessary to counter terrorism.

The US is more powerful than any country since the Roman Empire, but like Rome, the US is neither invincible nor invulnerable. Rome did not succumb to the rise of another empire, but to the onslaught of waves of barbarians. Modern high-tech terrorists are the new barbarians. The US cannot alone hunt down every suspected al-Qaeda leader. Nor can it launch a war whenever it wishes without alienating other countries.

The four-week war in Iraq was a dazzling display of the US' hard military power that removed a vicious tyrant. But it did not remove the US' vulnerability to terrorism. It was also costly in terms of our soft power to attract others.

In the aftermath of the war, polls showed a dramatic decline in the popularity of the US even in countries like Britain, Spain and Italy, whose governments backed the war. The US' standing plummeted in Islamic countries, whose support is needed to help track the flow of terrorists, tainted money and dangerous weapons.

The war on terrorism is not a clash of civilizations -- Islam versus the West -- but a civil war within Islamic civilization between extremists who use violence to enforce their vision and a moderate majority who want things like jobs, education, health care and dignity as they pursue their faith. The US will not win unless the moderates win.

American soft power will never attract bin Laden and his fellow extremists; only hard power can deal with these people. But soft power will play a crucial role in attracting moderates and denying the extremists new recruits.

Trojan horses

During the Cold War, the West's strategy of containment mixed the hard power of military deterrence with the soft power of attracting people behind the Iron Curtain. Behind the wall of military containment, the West ate away at Soviet self-confidence with broadcasts, student and cultural exchanges and the success of capitalist economics. As a former KGB official later testified: "Exchanges were a Trojan horse for the Soviet Union. They played a tremendous role in the erosion of the Soviet system."

In retirement, former US president Dwight Eisenhower said that he should have taken money from the defense budget to strengthen the US Information Agency.

With the Cold War's end, Americans became more interested in budget savings than in investing in soft power. Last year, a bipartisan advisory group reported that the US was spending only US$150 million on public diplomacy in Muslim countries, an amount it called grossly inadequate.

Indeed, the combined cost for the State Department's public diplomacy programs and all of the US' international broadcasting is just over US$1 billion, about the same amount spent by Britain or France, countries that are one-fifth the US' size and whose military budgets are only 25 percent as large. No one would suggest that the US spend as much to launch ideas as to launch bombs, but it does seem odd that the US spends 400 times as much on hard power as on soft power. If the US spent just 1 percent of the military budget on soft power, it would quadruple its current spending on this key component of the war on terrorism.

If the US is to win that war, its leaders are going to have to do better at combining soft and hard power into "smart power."

Joseph Nye is dean of Harvard's Kennedy School of Government, and author of Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

Concerns that the US might abandon Taiwan are often overstated. While US President Donald Trump’s handling of Ukraine raised unease in Taiwan, it is crucial to recognize that Taiwan is not Ukraine. Under Trump, the US views Ukraine largely as a European problem, whereas the Indo-Pacific region remains its primary geopolitical focus. Taipei holds immense strategic value for Washington and is unlikely to be treated as a bargaining chip in US-China relations. Trump’s vision of “making America great again” would be directly undermined by any move to abandon Taiwan. Despite the rhetoric of “America First,” the Trump administration understands the necessity of

US President Donald Trump’s challenge to domestic American economic-political priorities, and abroad to the global balance of power, are not a threat to the security of Taiwan. Trump’s success can go far to contain the real threat — the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) surge to hegemony — while offering expanded defensive opportunities for Taiwan. In a stunning affirmation of the CCP policy of “forceful reunification,” an obscene euphemism for the invasion of Taiwan and the destruction of its democracy, on March 13, 2024, the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) used Chinese social media platforms to show the first-time linkage of three new

The military is conducting its annual Han Kuang exercises in phases. The minister of national defense recently said that this year’s scenarios would simulate defending the nation against possible actions the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) might take in an invasion of Taiwan, making the threat of a speculated Chinese invasion in 2027 a heated agenda item again. That year, also referred to as the “Davidson window,” is named after then-US Indo-Pacific Command Admiral Philip Davidson, who in 2021 warned that Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) had instructed the PLA to be ready to invade Taiwan by 2027. Xi in 2017

If you had a vision of the future where China did not dominate the global car industry, you can kiss those dreams goodbye. That is because US President Donald Trump’s promised 25 percent tariff on auto imports takes an ax to the only bits of the emerging electric vehicle (EV) supply chain that are not already dominated by Beijing. The biggest losers when the levies take effect this week would be Japan and South Korea. They account for one-third of the cars imported into the US, and as much as two-thirds of those imported from outside North America. (Mexico and Canada, while