I have often wondered why Karl Popper ended the dramatic peroration of the first volume of his Open Society and Its Enemies with the sentence: "We must go on into the unknown, the uncertain and insecure, using what reason we have to plan for both security and freedom." Is not freedom enough? Why put security on the same level as that supreme value?

Then one remembers that Popper was writing in the final years of World War II. Looking around the world in 2004, you begin to understand Popper's motive: Freedom always means living with risk, but without security, risk means only threats, not opportunities.

Examples abound. Things in Iraq may not be as bad as the daily news of bomb attacks make events there sound; but it is clear that there will be no lasting progress towards a liberal order in that country without basic security. Afghanistan's story is even more complex, though the same is true there. But who provides security, and how?

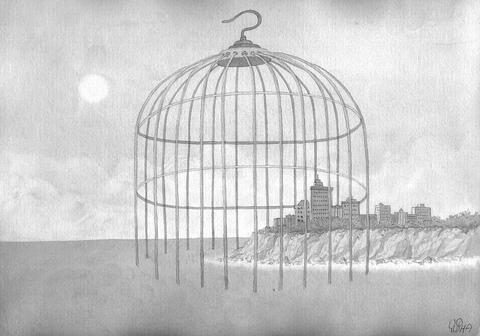

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

In Europe and the West, there is the string of terrorist acts -- from those on the US in 2001 to the pre-election bombings in Madrid -- to think about. London's mayor and police chief have jointly warned that terrorist attacks in the city are "inevitable." Almost every day there are new warnings, with heavily armed policemen in the streets, concrete barriers appearing in front of embassies and public buildings, stricter controls at airports and elsewhere -- each a daily reminder of the insecurity that surrounds us.

Nor is it only bombs that add to life's general uncertainties. Gradually, awareness is setting in that global warming is not just a gloom and doom fantasy. Social changes add to such insecurities. All at once we seem to hear two demographic time-bombs ticking: The continuing population explosion in parts of the third world, and the astonishing rate of aging in the first world. What will this mean for social policy? How will mass migration affect countries' cultural heritage?

There is also a widespread sense of economic insecurity. No sooner is an upturn announced than it falters. At any rate, employment seems to have become decoupled from growth. Millions worry about their jobs -- and thus the quality of their lives -- in addition to fearing for their personal security.

Such examples serve to show that the most disquieting aspect of today's insecurity may well be the diversity of its sources, and that there are no clear explanations and simple solutions. Even a formula like "war on terror" simplifies a more complex phenomenon.

So what should we do? Perhaps we should look at Popper again and remember his advice: To use what reason we have to tackle our insecurities.

In many cases this requires drastic measures, particularly insofar as our physical security is concerned. But while it is hard to deny that such measures are necessary, it is no less necessary to remember the other half of the phrase: "Security and freedom."

Checks on security measures that curtail the freedoms that give our lives dignity are as imperative as protection. Such checks can take many forms. One is to make all such measures temporary by giving these new laws and regulations "sunset clauses" that limit their duration. Security must not become a pretext for the suspending and destroying the liberal order.

A second requirement is that we look ahead more effectively. It is not necessary for us to wait for great catastrophes to occur if we can see them coming. Holland does not have to sink into the North Sea before we do something about the world's climate; pensions do not have to decline to near-zero before social policies are adjusted.

A third need is to preserve, and in many cases to recreate, what one might call islands of security. Globalization must become "glocalization": There is value in the relative certainties of local communities, small companies, human associations. Such islands are not sheltered and protected spaces, but models for others. They prove that up to a point security can be provided without loss of freedom.

There remains the most fundamental issue of attitude. It is debatable whether governments should ever frighten their citizens by painting the horror scenario of "inevitable" attack. The truth -- to quote Popper again -- is that "we must go on into the unknown, the uncertain and insecure," come what may.

Today's instabilities may be unusually varied and severe, but human life is one of ceaseless uncertainty at all times. Such uncertainty can lead to a frozen state of near-entropy. More frequently, uncertainty leads to someone claiming to know how to eliminate it -- frequently through arbitrary powers that benefit but a few.

False gods have always profited from a widespread sense of insecurity. Against them, an active effort to tackle the risks around us is the only answer. Perhaps we need a new Enlightenment to spread the confidence we need to live with insecurity in freedom.

Ralf Dahrendorf, author of numerous acclaimed books and a former European commissioner from Germany, is a member of the British House of Lords, a former rector of the London School of Economics and a former warden of St. Antony's College, Oxford.

Copyright: Project Syndicate/Institute for Human Sciences

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion