The search for a new managing director of the IMF provides a keen reminder of how unjust today's international institutions are. Created in the postwar world of 1945, they reflect realities that have long ceased to exist.

The organization and allocation of power in the UN, the IMF, the World Bank, and the G7 meetings reflects a global equilibrium that disappeared long ago. After World War II, Germany and Japan were the defeated aggressors, the Soviet Union posed a major threat, and China was engulfed in a civil war that would bring Mao Zedong's

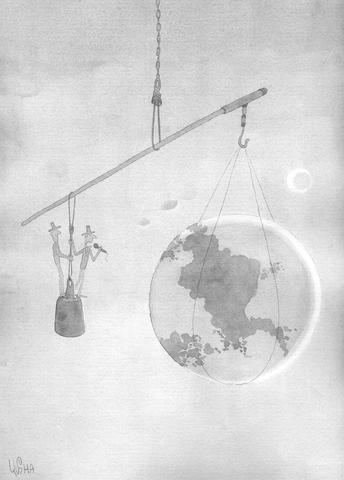

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

There were 74 independent countries in the world in 1945; today there are 193. Outside of China, Cuba and North Korea communism is popular only in West European cafes and a few US college campuses. Germany is reunited and much of the Third World is growing faster than the First World, with computer software built in Bangalore and US graduate programs, including business schools, receiving thousands of application from smart Chinese students.

The whole world has turned upside down, and yet France and the UK, for example, retain permanent seats on the UN Security Council. This made sense in 1945; it does not today. Why France and the UK and not Germany or Japan, two much larger economies? Or India and Brazil, two huge countries?

Does it really make sense that two EU member countries hold a veto power on the Security Council while the Third World (outside of China) is completely unrepre-sented? The EU does not have a common foreign policy and it will not have one in the foreseeable future, but this is no reason to continue to provide a preference to France and the UK. If Europe is really serious about a common foreign policy, does the current arrangement make any sense? True, France and the UK do have the best foreign services in Europe, but this is reversing cause and effect. France and the UK maintain this capability because they continue to have foreign-policy relevance.

Europe's over-representation extends beyond the Security Council. While a European foreign policy does not exist, Europe has some sort of common economic policy: 12 of the 15 current members have adopted the euro as their currency and share a central bank. Nevertheless Germany, France, Italy and the UK hold four of the seven seats at the G7 meetings.

Indeed, the situation is even more absurd when G7 finance ministers meet: the central bank governors of France, Germany and Italy still attend these meetings, even though their banks have been reduced to local branches of the European Central Bank, while its president -- these countries' real monetary authority -- is a mere "invited guest." Shouldn't there be only one seat for Europe?

Of course, European leaders strongly oppose any such reform: they fear losing not only important opportunities to have their photographs taken, but real power as well. But how much power they really wield in the G7 is debatable: the US president, secretaries of state and treasury, and the chairman of the US Federal Reserve almost certainly get their way more easily in a large, unwieldy group than they would in a smaller meeting where Europe spoke with a single voice.

The current search for a new IMF head continues this pattern. The IMF managing director is a post reserved for a West European; the Americans have the World Bank.

This division of jobs leaves out the developing countries, many of which are "developing" at a speed that will make them richer than Europe in per capita terms quite soon.

What about the 1 billion Indians or the 1.2 billion Chinese? Shouldn't one of them at least be considered for such a post? What about the hard-working and fast-growing South Koreans? Why should they not be represented at the same level as Italy or France? What about Latin American success stories like Chile and perhaps Mexico or Brazil?

The Europeans don't even seem to care very much about the job. After all, Horst Kuhler, the IMF managing director, resigned from a job that commands the world's attention to accept the nomination to become president of Germany, a ceremonial post with no power whatsoever, not even inside Germany.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development is located in Paris, the UN's Food and Agriculture Organization in Rome, and the list goes on. Simply put, Western Europe is overrepresented in international organizations, given its size in terms of GDP and even more so in terms of population. It is thus not surprising that some Europeans -- particularly the French -- are so reluctant to reform the international organizations, even in terms of cutting waste and inefficiency at the UN. After all, might not someone then suggest that the first step in such a reform would be to reduce Europe to a single seat on the Security Council?

Europe is being myopic. A single seat -- at the UN, the IMF or the World Bank -- would elevate Europe to the same level as the US and would augment, rather than diminish, its global influence.

The over-representation of Western Europe and the under-representation of growing de-veloping countries cannot last. Indeed, it is already creating tensions.

Obsolete dreams of grandeur should not be allowed to interfere with a realistic and fair distribution of power in the international arena.

Alberto Alesina is professor of economics at Harvard University; Francesco Giavazzi is professor of economics at Bocconi University, Milan. Their e-mail addresses are: aalesina@harvard.edu and francesco.giavazzi@uni-bocconi.it.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

Concerns that the US might abandon Taiwan are often overstated. While US President Donald Trump’s handling of Ukraine raised unease in Taiwan, it is crucial to recognize that Taiwan is not Ukraine. Under Trump, the US views Ukraine largely as a European problem, whereas the Indo-Pacific region remains its primary geopolitical focus. Taipei holds immense strategic value for Washington and is unlikely to be treated as a bargaining chip in US-China relations. Trump’s vision of “making America great again” would be directly undermined by any move to abandon Taiwan. Despite the rhetoric of “America First,” the Trump administration understands the necessity of

In an article published on this page on Tuesday, Kaohsiung-based journalist Julien Oeuillet wrote that “legions of people worldwide would care if a disaster occurred in South Korea or Japan, but the same people would not bat an eyelid if Taiwan disappeared.” That is quite a statement. We are constantly reading about the importance of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC), hailed in Taiwan as the nation’s “silicon shield” protecting it from hostile foreign forces such as the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), and so crucial to the global supply chain for semiconductors that its loss would cost the global economy US$1

US President Donald Trump’s challenge to domestic American economic-political priorities, and abroad to the global balance of power, are not a threat to the security of Taiwan. Trump’s success can go far to contain the real threat — the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) surge to hegemony — while offering expanded defensive opportunities for Taiwan. In a stunning affirmation of the CCP policy of “forceful reunification,” an obscene euphemism for the invasion of Taiwan and the destruction of its democracy, on March 13, 2024, the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) used Chinese social media platforms to show the first-time linkage of three new

Sasha B. Chhabra’s column (“Michelle Yeoh should no longer be welcome,” March 26, page 8) lamented an Instagram post by renowned actress Michelle Yeoh (楊紫瓊) about her recent visit to “Taipei, China.” It is Chhabra’s opinion that, in response to parroting Beijing’s propaganda about the status of Taiwan, Yeoh should be banned from entering this nation and her films cut off from funding by government-backed agencies, as well as disqualified from competing in the Golden Horse Awards. She and other celebrities, he wrote, must be made to understand “that there are consequences for their actions if they become political pawns of