Traveling from Berlin to Riga, Latvia's capital, is an eye-opener, because you get to see much of what is going wrong in European integration nowadays, just months before a further 10 states join the EU, bringing it up to 25 from the original six.

In Berlin before I left, German Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder had just welcomed his French and British colleagues for an exchange of views on the state and future of the union. They were, the chiefs of the three largest members of the EU declared, only advancing proposals; nothing could be further from their minds than to form a steering group to run the affairs of the enlarged union, even if henceforth they would meet again at more or less regular intervals.

If they really hoped to be believed, they should have listened to my interlocutors in the old city of Riga over the next few days.

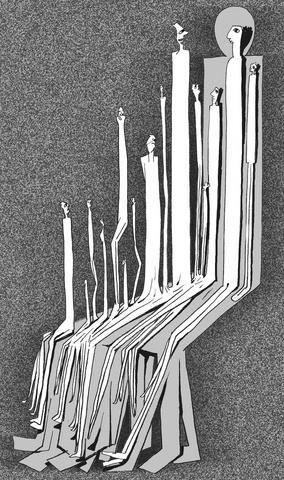

ILLUSTRATION: MOUNTAIN PEOPLE

The three Baltic countries -- Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania -- will be among the smallest members when they join the union on May 1, their total of 6 million people representing just 1.5 percent of the then EU's population. Yet in marked contrast to the smaller nations that half a century earlier had joined France, Italy and Germany in launching the union's forerunner, the European Economic Community, the new arrivals are digging in their heels, demanding equal rights. Although as small countries they have learnt that the big ones usually get their way, they deeply resented the Berlin meeting because they see in it an attempt to limit their rights in the club they are about to join.

The attitudes of the EU's big and small countries suggest that European integration's basic bargain is no longer regarded as fair. Under that bargain, the bigger states accepted restraints on their power in order to increase the weight of the union as a whole while the smaller ones realized that being part of the club gave them a chance they would not have otherwise, namely to participate in the shaping of common policies. Europe, once the continent of power clashes and balances, became a community of law where big and small follow common rules to reach common decisions.

Now, as Berlin and Riga suggest, power is returning as the trump card. The authority of the big countries derives not from their European credentials but from their power ranking; the resentment of the smaller countries flows not from a different notion of integration but from their fear of losing out. What used to succeed as a win-win arrangement for big and small alike, now appears as a zero-sum game to many of them.

There are explanations for this. In a union of soon 25 members, it will be increasingly difficult to let everyone have a say and to generate consensus. On issues of foreign and security policy, moreover, agreement among the heavyweights of the union is essential for common action.

Unless France, Britain and Germany agree, there is little chance the union can act effectively on the international stage. At the same time, giving up sovereignty for the sake of integration is tough for the new members from Eastern Europe that only a decade ago wrested the right to govern themselves from Soviet control.

Yet big and small alike must realize that their current disposition implies the slow suffocation of Europe's most exciting and successful experiment in bringing peace and prosperity to the old continent. To save it, the bigger ones will indeed have to take the lead. But instead of offering ready solutions for the rest to endorse, leadership will have to consist of working with the other members, patiently and discretely, so that all, or at least most, feel they are involved in formulating common positions.? Only then will the smaller members feel adequately respected. Only then will all members again concentrate on getting things done for all instead of each of them concentrating on getting the most out of it for himself.

There are many who believe that this kind of patient leadership is incompatible with a union of 25. France and Germany, acting together, were able for many years to provide this sort of leadership, and this should be recalled. Whenever they came out with a proposal, the others gave them credit that it was in the interest of the union as a whole; whenever there was a deadlock, the others looked for leadership from Paris and Bonn/Berlin to overcome it.

In the past, German governments rightly took pride in being seen by the smaller members as their best partner, essential for the Franco-German leadership to work. Today, Germany has joined France in neglecting the smaller members for the sake of being recognized as one of the big boys. So the Franco-German couple has lost the credit it once enjoyed. Bringing in Britain is an admission of that fact.

But because Britain remains lukewarm on European integration, the threesome can never serve as the motor for moving Europe forward. Even in an enlarged union, only France and Germany can do that job, provided they make a determined effort to regain the trust of the other, mostly smaller members, old and new. While these expect little from an often indifferent France, they still, as the discussions in Riga suggest, would be disposed to putting their trust in Germany -- if only German governments once again show they care.

Christoph Bertram is director of the German Institute for International and Security Affairs in Berlin.

Concerns that the US might abandon Taiwan are often overstated. While US President Donald Trump’s handling of Ukraine raised unease in Taiwan, it is crucial to recognize that Taiwan is not Ukraine. Under Trump, the US views Ukraine largely as a European problem, whereas the Indo-Pacific region remains its primary geopolitical focus. Taipei holds immense strategic value for Washington and is unlikely to be treated as a bargaining chip in US-China relations. Trump’s vision of “making America great again” would be directly undermined by any move to abandon Taiwan. Despite the rhetoric of “America First,” the Trump administration understands the necessity of

US President Donald Trump’s challenge to domestic American economic-political priorities, and abroad to the global balance of power, are not a threat to the security of Taiwan. Trump’s success can go far to contain the real threat — the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) surge to hegemony — while offering expanded defensive opportunities for Taiwan. In a stunning affirmation of the CCP policy of “forceful reunification,” an obscene euphemism for the invasion of Taiwan and the destruction of its democracy, on March 13, 2024, the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) used Chinese social media platforms to show the first-time linkage of three new

If you had a vision of the future where China did not dominate the global car industry, you can kiss those dreams goodbye. That is because US President Donald Trump’s promised 25 percent tariff on auto imports takes an ax to the only bits of the emerging electric vehicle (EV) supply chain that are not already dominated by Beijing. The biggest losers when the levies take effect this week would be Japan and South Korea. They account for one-third of the cars imported into the US, and as much as two-thirds of those imported from outside North America. (Mexico and Canada, while

The military is conducting its annual Han Kuang exercises in phases. The minister of national defense recently said that this year’s scenarios would simulate defending the nation against possible actions the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) might take in an invasion of Taiwan, making the threat of a speculated Chinese invasion in 2027 a heated agenda item again. That year, also referred to as the “Davidson window,” is named after then-US Indo-Pacific Command Admiral Philip Davidson, who in 2021 warned that Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) had instructed the PLA to be ready to invade Taiwan by 2027. Xi in 2017