Merrimack looked like any other slice of smalltown America. Nestled among the pinewoods of New Hampshire, its white clapperboard houses and church spire were spoiled only by the inevitable cluster of fast food outlets.

But today Merrimack was far from ordinary. It was part of a revolution sweeping American politics. The first clue was the man on a street corner waving traffic towards the high school and holding a sign proclaiming: "The Doctor is in." Though it was a Saturday the car park was full. Inside the dining hall hundreds of people had gathered to see Dr. Howard Dean, the man who has come from nowhere to lead the Democratic Party race for the White House. The man who by next year could be the most powerful person in the world.

It felt like a church meeting. A chorus of dignitaries sat on the stage. The school principal, Ken Coleman, gave a speech to prepare for Dean's entrance. "We have seen terrible things happening in America," he warned. "We either nominate Howard Dean or we have four more years of George Bush."

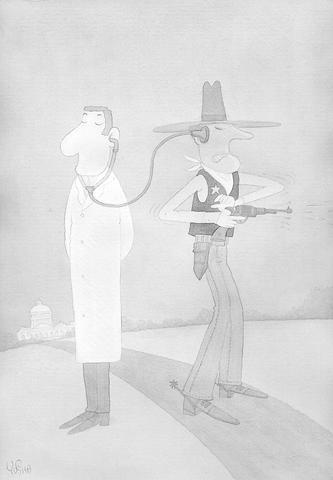

YUSHA

Dean bounded up and was greeted as a saviour. The crowd -- housewives, professionals, grandparents with toddlers hauled along for the ride -- stood and applauded. Stocky and red-faced, Dean looked an unlikely hero, but he is getting used to this sort of attention. "We're going to have a little fun at the president's expense," he promised with a smile. First target was the economy. He cited figures showing a boom in productivity and asked rhetorically: "Anyone got their jobs back?" His delivery was well-paced, mixing rehearsed points with ad libs. "We can do better than this," he insisted.

When it was over the crowd surged forward. Dean disappeared among the autograph hunters. Eventually he was hustled out of the door, leaving a happy crowd and exasperated reporters, one of whom had been physically prevented from asking Dean any questions. "It is amazing how quickly `frontrunner-itis' sets in," lamented Howard Kurtz of the Washington Post. "I remember him a year back when he would have been desperate for the attention."

But a year is a long time in politics ... particularly American politics. There is nothing else like the New Hampshire primary in Western democracy. It is raw politics, where those seeking to become president of America must first win the backing of the citizens of this tiny New England state. And this time things in the "Granite State" are different. The Democrats are angry, angrier than at any time since Richard Nixon -- perhaps even the Great Depression. Bush, with his post-Sept. 11 agenda, has divided America and also the Democratic Party. The atmosphere on the streets and in the town halls of New Hampshire is of political combat at its most vicious.

That may well set the tone for the national election to come -- but first New Hampshire must be won. Its importance stems from the byzantine way America selects presidential candidates. For Republican George W. Bush -- running unopposed -- there is no problem. But the Democrats must whittle down a field of nine hopefuls. This is done with state-by-state elections by party members. Though Iowa now votes first, New Hampshire is still seen as the proving ground. This wooded, mountainous state of just 1.2 million people punches far above its weight. At stake are the fabled three M's: momentum, media and money. Those who triumph here expect to reap all three and sweep the country to secure the nomination.

This field is larger than usual. There is the retired general, Wesley Clark; the firebrand preacher Al Sharpton, and former ambassador Carol Moseley Braun -- the first black woman to ever run for president; there are also Democrat warhorses like senators Dick Gephardt, Joe Lieberman and John Kerry; and the Clintonesque John Edwards, a Southern charmer. Finally, there's Dennis Kucinich, an avowed radical. It's a colorful bunch and each is treading the same worn path as every president before them: the path through New Hampshire.

It is house-to-house political warfare. Candidates set up camp in the state. Local politicians, normally passed over by Washington bigwigs, suddenly find themselves courted by all nine of the runners. Politicians, who a year from now might live in the White House, are forced to confront real people. "We get to look them in the eye and they can't duck tough questions. Madison Avenue can't get you elected in New Hampshire," said local Democrat activist Paul Needham. He should know, having met every serving president since 1976. "It's easy. I just live in New Hampshire and have a pulse," he said.

The media have dubbed Dean's supporters the "Deaniacs." They are young idealists who have turned the campaign into a phenomenon. They work hard, play hard, sleep on each other's floors and have the time of their lives. They also get a whiff of power and valuable CV points. Days start at 8.30am and finish near midnight. They bubble over with enthusiasm at morning meetings.

Driving to a college town in a car full of Deaniacs is a lesson in what it is to be young and enthusiastic. Chad Bolduc, 22, and Emily Barson, 23, shout their dedication above the music blaring from the radio as they scout a location for an upcoming debate. Dean has inspired them to take time off from -- or give up -- their studies. Bolduc once acted as Dean's driver for a day of campaigning. It left him breathless.

"I could see he is such a good guy. He is not bullshitting us at all," he said. Bolduc does not think his college will let him come back due to the time he has spent working for Dean. But he does not care. There will always be another college, but not another campaign like this.

Another big difference in Dean's campaign lies in cyberspace. He has mobilized the Internet in a way all his rivals have tried and failed to copy. He raises huge sums from online donations. Across the country "meet-ups" have been organized over the Internet, putting together an unprecedented national network of young, professional activists. When Bush's campaign raises a million dollars at a fundraiser, Dean's activists rally over the Internet to match it. They usually succeed. Staffers and supporters swap ideas using online journals or blogs.

This is the future. For a look at the past, one need go no further than the faltering Joe Lieberman. He should have been a frontrunner. He was Al Gore's running mate in 2000 and is a moderate who would appeal to the middle ground. But this is not a year for moderation. Even Gore has plumped for Dean.

Lieberman looks old-fashioned now. Ham-fisted slogans like "A Joe-vember to remember" and "Liebermania" have fallen flat. At a diner in the northern town of Littleton, Lieberman's problems were plain to see. It was 8.30am and the three customers were outnumbered by the press. But Lieberman sat down and chatted with them anyway, looking like any other customer -- aside from the three secret service agents hovering nearby. At one point he noticed a motivational note posted on the kitchen wall. "Act as if it is impossible to fail," he read out loud. But it seemed a bit late for that.

This is a war election. It is there in the yellow ribbons tied to trees and the American flags hung from freeway overpasses. It is also there on the TV news each night in reports of the dead and maimed GIs in Iraq. It is the issue that divides the country, and the issue that gave birth to the Howard Dean phenomenon.

Dean's opposition to the war, initially seen as a handicap, has now turned into his strength. He used it to gain support but also to attack his Democrat rivals. At every meeting Dean speaks out against the war. But just as the war helped make him, it can destroy him too, exposing him on the issue of national security -- the Democrats' traditional Achilles heel. The capture last month of former Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein took some of the wind out of Dean's sails, but he held firm, arguing that capturing Saddam would not make America safer from terrorists. If the American body count continues to rise then Saddam emerging from his spider-hole will rapidly become just a memory.

Yet the war shapes other campaigns too, and if Dean falters then there is another candidate on the anti-war ticket: General Wesley Clark. When Clark announced his run he seemed a Democrat dream. He is a four-star general, who led NATO to victory in Kosovo, and yet has been a critic of the war in Iraq. Unlike Dean, it would be hard to question Clark on matters of patriotism and national security.

At a college hall in the student town of Exeter, he asked all the veterans to stand up. When they did so, Clark marched to the back of the auditorium and grasped one corner of a huge American flag. "This is our flag," he told the crowd. "We served under it. We have fought for it. We watched brave men and women buried under it."

It was pure showmanship, seemingly made for an American electorate in time of conflict. But it is not enough. Clark's campaign has been slow to get started. He entered the race too late to build up the effective local organization that it takes to win primaries. He continually harks back to his military record, no matter what the subject. He has been lambasted for having few policies on jobs, healthcare or the environment. Clark now trails Dean badly.

If Dean becomes president, America could be rebuilt in the style of the good doctor's Vermont. But to those eager to portray Dean as a wild-eyed liberal (in a country where liberal is a dirty word) Dean's record in Vermont comes as a surprise. He governed as a fiscal conservative, angering the left-wing of his state Democratic party. He insisted on a balanced budget and set up a "rainy day" fund for the state's surplus. Although he signed into law gay "civil unions" giving homosexual partners the same legal status as married couples, he only did so after a court decision recommending it. He dislikes gun control (Vermont is a hunting state), and has even won plaudits from the National Rifle Association. He promises action on environmental issues but knows he will never end America's love affair with the car. "I have seen the car park. It is full of SUVs," he tells each audience he speaks too. "We have SUVs in Vermont too. Nobody's going to throw Americans out of their SUVs."

So who is this country doctor shaking America's political firmament? He is not from Vermont at all. Dean's rush-released autobiography begins with the words, "My family comes from Sag Harbor," referring to a sleepy Long Island resort town. But, in fact, Dean is a New Yorker. And a rich one, too. He grew up the son of a stockbroker on Park Avenue. He went to school at the ultra-posh Downing School on East 62nd Street. Sag Harbor, which Dean eulogizes as a childhood place of swimming, fishing and stealing potatoes, was just a holiday destination.

The family was traditional. His father, also Howard Dean, was known in the family as "Big Howard." He was an avid Republican. The younger Dean, "Little Howard," stood out. He asked to be roomed with black students while at Yale. Big Howard refused to let his son's new friends visit the family home. Everything about Dean's background should have produced another stockbroker or a lawyer. Instead Dean chose to become a doctor. After graduation from medical school he moved to Vermont to set up home with his wife, Judith Steinberg, a Jewish medic. He moved into politics (his first political act was campaigning for Jimmy Carter) and rose to be deputy governor before the sudden death of his boss called him to the top job in the state.

The Deans are a private couple. When Dean was Vermont's governor his wife rarely attended state functions. She does not campaign for him. Their teenage son Paul had a recent run-in with police over the theft of alcohol from a country club. Dean refused to answer questions on the matter. Now it appears that the pressure of campaigning is already changing things. Last week Dean said his wife was preparing to do some television interviews and might appear in a campaign advert.

At heart, Dean is still a country doctor. He is a mix of "small c" conservatism and DIY liberalism. When he was deputy governor he still ran his doctor's practice. His wife plans to open a practice in Washington if he wins the White House. Dean can only be understood through the prism of his profession. The campaign trail is already littered with Dean the Doctor stories; aides treated at the roadside after minor accidents; Dean stopping everything to administer a quick check-up. Yet he plays the game of politics hard. Addressing one meeting on what he thought of Bush's record in office, he gave a simple diagnosis. The American public, he said, was being "shafted."

Dean tells the story of sitting at his desk, reading a newspaper full of bad news, and suddenly asking himself if he was just going to complain ... or do something about it. The answer led to a presidential campaign that began far below the radar of national politics. Slipping over the Vermont border, Dean addressed tiny gatherings. He worked the local media. His stroke of genius was hiring Joe Trippi, a former Silicon Valley mogul, as his campaign manager. That ensured the exploitation of cyberspace. And then there was his passion, which seeped through whatever medium he used. By the time Dean burst on to the national scene last summer, with more cash than any of his rivals, he was already old news to the legions of tech-savvy supporters who had been following him on the Internet. It was a classic combination of new and old, of pounding the streets while working the inboxes.

In any US election there is one simple rule: money wins. Against all odds, Dean now has the money. His campaign has raked in at least US$25m, more than any other. Now, controversially, Dean has foregone capped state funding in the hope of being able to raise more alone. That sabotaged years of Democrat efforts to take the cash out of politics, but Dean's supporters argue that when you are facing Bush -- who also waives state funding -- you have no choice.

Dean spends his cash, too. For all the hype over his grassroots campaign, the airwaves are full of Dean adverts. But he is not the only one with money. Others have the means to fight on, hoping that Dean slips up as an increasingly prying media casts a spotlight over every aspect of his background. Certainly that is John Edwards's great hope. If the 2004 campaign is to see the emergence of a Bill Clinton figure then Edwards is the man. He is working the streets as hard as anyone, buoyed by a huge personal fortune.

Standing in the back of Oliver's Restaurant in Tilton, Edwards was the epitome of an American candidate, pleading in his southern accent for people's votes as he ended his pitch thus: "I still believe in an America where the son of a millworker can beat the son of a president for the White House." It was the fifth time he had used the phrase that day.

Not that he looks like a millworker's son any more. Born to a poor family in South Carolina, he left behind his past to become one of America's richest lawyers. To critics he is an "ambulance chaser," winning inflated compensation claims for his clients. To supporters he stands up for victims against huge institutions. Either way, Edwards's story, which includes a conversion to politics after the death of his beloved eldest son, is compelling. And he milks it well.

Edwards knows he does not have to win New Hampshire. He must just survive it. The key primary after Iowa and New Hampshire is South Carolina. Edwards often tops the polls in his birth state. If he gets enough support to stay alive until South Carolina votes, then he may yet win the White House. This is what Bill Clinton did in 1992. Paul Tsongas won New Hampshire back then, and who remembers him?

--Continued tomorrow--

As strategic tensions escalate across the vast Indo-Pacific region, Taiwan has emerged as more than a potential flashpoint. It is the fulcrum upon which the credibility of the evolving American-led strategy of integrated deterrence now rests. How the US and regional powers like Japan respond to Taiwan’s defense, and how credible the deterrent against Chinese aggression proves to be, will profoundly shape the Indo-Pacific security architecture for years to come. A successful defense of Taiwan through strengthened deterrence in the Indo-Pacific would enhance the credibility of the US-led alliance system and underpin America’s global preeminence, while a failure of integrated deterrence would

It is being said every second day: The ongoing recall campaign in Taiwan — where citizens are trying to collect enough signatures to trigger re-elections for a number of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislators — is orchestrated by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), or even President William Lai (賴清德) himself. The KMT makes the claim, and foreign media and analysts repeat it. However, they never show any proof — because there is not any. It is alarming how easily academics, journalists and experts toss around claims that amount to accusing a democratic government of conspiracy — without a shred of evidence. These

Taiwan is confronting escalating threats from its behemoth neighbor. Last month, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army conducted live-fire drills in the East China Sea, practicing blockades and precision strikes on simulated targets, while its escalating cyberattacks targeting government, financial and telecommunication systems threaten to disrupt Taiwan’s digital infrastructure. The mounting geopolitical pressure underscores Taiwan’s need to strengthen its defense capabilities to deter possible aggression and improve civilian preparedness. The consequences of inadequate preparation have been made all too clear by the tragic situation in Ukraine. Taiwan can build on its successful COVID-19 response, marked by effective planning and execution, to enhance

Since taking office, US President Donald Trump has upheld the core goals of “making America safer, stronger, and more prosperous,” fully implementing an “America first” policy. Countries have responded cautiously to the fresh style and rapid pace of the new Trump administration. The US has prioritized reindustrialization, building a stronger US role in the Indo-Pacific, and countering China’s malicious influence. This has created a high degree of alignment between the interests of Taiwan and the US in security, economics, technology and other spheres. Taiwan must properly understand the Trump administration’s intentions and coordinate, connect and correspond with US strategic goals.