Undoing a weapons program is one of the rarest of decisions for an absolute leader.

After South Africa's apartheid government was replaced by black majority rule, South Africa astonished the world by disclosing that it had developed six nuclear weapons and then allowing the UN nuclear inspections agency, the International Atomic Energy Agency, to disarm it. That decision, in effect, was the result of a naturally occurring "regime change."

Libya's important and welcome decision to abandon its unconventional weapons programs is all the more interesting since the same government that got Libya into the business of developing forbidden weapons has now ordered the change of course.

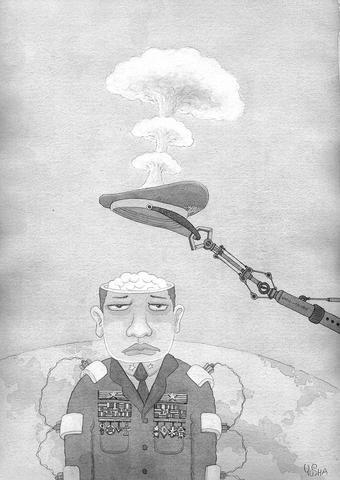

ILLUSTRATION MOUNTAIN PEOPLE

But the larger issue is whether North Korea and Iran can be similarly disarmed and, if so, how best to go about it.

Libya never got very far down the nuclear road and its weapons programs were not enough of a worry to rate inclusion in the "axis of evil" proclaimed by US President George W. Bush in his State of the Union speech in 2002 (Iraq, Iran and North Korea made the cut).

While Libya had acquired centrifuges on the black market, it had not yet assembled them into a large-scale cascade for producing highly enriched uranium. When it came to a nuclear arsenal, Libya was abandoning a distant -- but still dangerous -- dream, not a real ability.

North Korea and Iran are much tougher cases and ultimately a far more important test of the Bush administration's efforts to roll back weapon programs through a mixture of force and diplomacy, rather than the more traditional reliance on weak international treaties and policing.

US intelligence agents project that North Korea has already got one or two nuclear weapons and the ability to expand this presumed nuclear arsenal. Iran has also been working energetically toward developing a nuclear weapons capacity, US intelligence says. It remains to be seen if the signing this month of an agreement on international inspections will eventually halt those efforts.

The turnabout by the Libyan leader, Colonel Muammar Qaddafi -- and the secret British and US diplomacy that encouraged it -- amount to just one step on the road to stopping proliferation, and the question is how to take the next ones.

From the start, the Bush team has said that their policy toward Iraq was about more than just Iraq. The Bush administration began the year with an audacious doctrine that held that removing former Iraqi president Saddam Hussein from power would send a cautionary message to weapons proliferators and help remake the Middle East.

As it heads into an election year, the Bush administration has highlighted the role that US power may have played in changing the Libyan leader's mind. Top Libyan officials, by contrast, have pointed to economic considerations.

The possibility of ending decades of punishing economic sanctions might indeed have led Qaddafi, who has ruled for 34 years and wants to stay in power, to chart a new course even if the Iraq war had not occurred.

Still, it may be that the US invasion of Iraq reinforced the message that the pursuit of forbidden weapons did not strengthen his government. The administration of former US president Ronald Reagan, after all, ordered Air Force F-111s and Navy A-6s to bomb Libya in 1986 after concluding that Libya was behind an attack on US servicemen in Europe.

There is no indication of a similar change of heart in North Korea, where there are indications that North Korean leader Kim Jong-il has drawn a very different lesson from the Iraq war. Having seen how the leader of Iraq was transformed into a prisoner, North Korea appears to have concluded that the best protection against a US intervention is a nuclear arsenal, the bigger the better.

Instead of renouncing its nuclear program, North Korea has in the past year advertised its supposed advances in making nuclear weapons. The Bush administration has turned particularly to China -- as well as to Russia, South Korea and Japan -- to try to advance diplomacy, but has in effect found itself with little leverage.

Threatening military force is not an option. War on the heavily armed Korean Peninsula would be a calamity. No Asian ally is prepared to back a policy of confrontation. With most of the US Army preoccupied with Iraq and Afghanistan, the US simply lacks the military muscle to marshal a credible threat.

In talks, North Korea has proved to be frustrating and possibly untrustworthy. The Bush administration, meanwhile, has oscillated between a hard-line policy of waiting for North Korea's collapse and trying to engage the North in bargaining.

If there is hope of replicating the Libyan reversal it may be in Iran.

First, Iran has not yet developed nuclear weapons. So it would be giving up a prospective, and not actual, ability. Second, a diplomatic process is already under way.

Gary Samore, a senior fellow at the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London and a former proliferation expert on the National Security Council under former US President Bill Clinton, notes that Iran has responded to diplomatic pressure -- from Europe and the US -- and temporarily suspended its previously clandestine efforts to enrich uranium at its Natanz site.

What is needed now is a permanent solution, one in which Iran will permanently forgo efforts to produce nuclear weapons materials by enriching uranium or producing plutonium.

European nations have offered Iran access to fuel supplies for a peaceful nuclear program if it gives up its ambitions to develop nuclear weapons.

Whether the US would be party to such a deal and whether Iran would embrace it, Samore notes, are unclear.

"In the case of North Korea the Libya model is unrealistic," he said in a telephone interview. "It is not plausible that the North Korean regime, given their perception of the world, will give up their missiles and chemical, biological and nuclear programs in exchange for better relations. They view them as essential for their survivability. The best you can do is to achieve limits."

If there is a chance to repeat the Libyan experience, he notes, "the test will come in Iran."

Concerns that the US might abandon Taiwan are often overstated. While US President Donald Trump’s handling of Ukraine raised unease in Taiwan, it is crucial to recognize that Taiwan is not Ukraine. Under Trump, the US views Ukraine largely as a European problem, whereas the Indo-Pacific region remains its primary geopolitical focus. Taipei holds immense strategic value for Washington and is unlikely to be treated as a bargaining chip in US-China relations. Trump’s vision of “making America great again” would be directly undermined by any move to abandon Taiwan. Despite the rhetoric of “America First,” the Trump administration understands the necessity of

US President Donald Trump’s challenge to domestic American economic-political priorities, and abroad to the global balance of power, are not a threat to the security of Taiwan. Trump’s success can go far to contain the real threat — the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) surge to hegemony — while offering expanded defensive opportunities for Taiwan. In a stunning affirmation of the CCP policy of “forceful reunification,” an obscene euphemism for the invasion of Taiwan and the destruction of its democracy, on March 13, 2024, the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) used Chinese social media platforms to show the first-time linkage of three new

If you had a vision of the future where China did not dominate the global car industry, you can kiss those dreams goodbye. That is because US President Donald Trump’s promised 25 percent tariff on auto imports takes an ax to the only bits of the emerging electric vehicle (EV) supply chain that are not already dominated by Beijing. The biggest losers when the levies take effect this week would be Japan and South Korea. They account for one-third of the cars imported into the US, and as much as two-thirds of those imported from outside North America. (Mexico and Canada, while

I have heard people equate the government’s stance on resisting forced unification with China or the conditional reinstatement of the military court system with the rise of the Nazis before World War II. The comparison is absurd. There is no meaningful parallel between the government and Nazi Germany, nor does such a mindset exist within the general public in Taiwan. It is important to remember that the German public bore some responsibility for the horrors of the Holocaust. Post-World War II Germany’s transitional justice efforts were rooted in a national reckoning and introspection. Many Jews were sent to concentration camps not